Contents

Page List

Guide

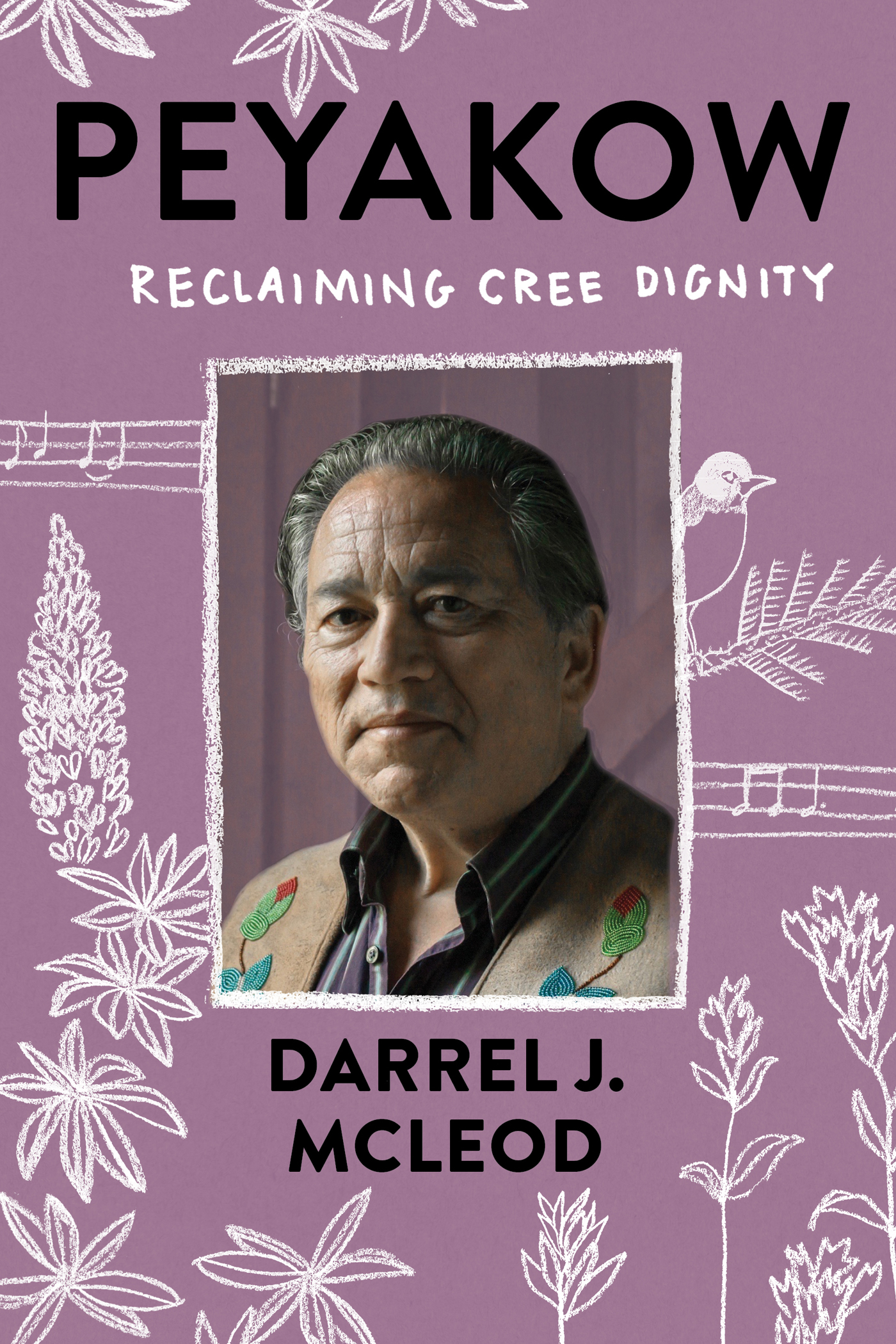

PEYAKOW

PEYAKOW

RECLAIMING CREE DIGNITY

Darrel J. McLeod

MILKWEED EDITIONS

2021, Text by Darrel J. McLeod

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Milkweed Editions, 1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415.

(800) 520-6455

milkweed.org

Published 2021 by Milkweed Editions

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Mary Austin Speaker

Cover photo by Ilja Herb; cover illustration by Mary Austin Speaker

21 22 23 24 255 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Milkweed Editions, an independent nonprofit publisher, gratefully acknowledges sustaining support from the Alan B. Slifka Foundation and its president, Riva Ariella Ritvo-Slifka; the Ballard Spahr Foundation; Copper Nickel; the Jerome Foundation; the McKnight Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; the National Poetry Series; the Target Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. Also, this activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. For a full listing of Milkweed Editions supporters, please visit milkweed.org.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McLeod, Darrel J., author.

Title: Peyakow : reclaiming Cree dignity / Darrel McLeod.

Other titles: Reclaiming Cree dignity

Description: First edition. | Minneapolis, Minnesota : Milkweed Editions, 2021. |

Summary: "Following his debut memoir, Mamaskatch, which masterfully portrayed a Cree coming-of-age in rural Canada, Darrel J. McLeod continues the poignant story of his adulthood in Peyakow"--Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016611 (print) | LCCN 2021016612 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571313973 (paperback) | ISBN 9781571317438 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: McLeod, Darrel J. | Cree Indians--Biography. | McLeod, Darrel J.--Family. | Canada. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada--Officials and employees--Biography. | Indigenous peoples--Canada--Government relations. | Indigenous peoples--Canada--Land tenure. | Indigenous men--Canada--Biography. | Indian gays--Canada--Biography. | Two-spirit people--Canada--Biography.

Classification: LCC E99.C88 M348 2021 (print) | LCC E99.C88 (ebook) | DDC 971.2004/973230092 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016611

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016612

Milkweed Editions is committed to ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book production practices with this principle, and to reduce the impact of our operations in the environment. We are a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources. Peyakow was printed on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper by McNaughton-Gunn.

Love is something that you can leave behind you when you dieit is that powerful.

JOHN FIRE LAME DEER (190376), LAKOTA HOLY MAN

Darrel James McLeodLapatakisiyegaso. Slave Lake ohci niya. Bertha Dora nigawi, Clifford James (Sonny) notawiy.

Ive been living in exile from my homeland for over five decades, separated from my people, my culture and language, the rivers and streams, hunting grounds and berry patchesthe entire ecosystem of which I am a part; an ecosystem that has been permanently altered. I can never recuperate the pristine creek we used to drink from; its life-giving water nurtured my nascent being. I can never revisit the idyllic meadows where as children countless cousins and I frolicked worry free from dawn to dusk in the territory where the spirits of our ancestors dwell to this day, a land now traversed by pipelines and penetrated by compressor stations and pumpjacks.

The birdsour constant companions and allieshave diminished in number. The monarch butterflies had all but disappeared but seem to be making a comeback. And the water level of the rivers has gone down by approximately one-third.

After laborious research and deep reflection over the last few years, I now grasp how my extended family, once proud and strong, independent and thriving, became disenfranchised and impoverished while the society around us grew increasingly affluent. In the pages of this book, I write what Ive come to understand about the colonization of my people and tell the story of how I struggled to turn around our dystopian lives, striving to salvage some degree of happiness and well-being not only for myself and my family but also for Indigenous individuals and peoples in Canada and other parts of the world.

sawyimik kahkiyaw nittminnak mna niwhkmkaninnak

Contents

Miyoskamin

I SKIPEWTHE WATER WAS up to there. The reedy plains near the mouth of Ayahciniyiw spy, the Slave River, were submersed, the confluent streams high. Widespread flooding was still possible. The ice barrage, with its monstrous, angular protrusions, had broken into boulder-sized chunks that floated steadily downstream, diminishing in size as they moved.

Miyoskamin was well underway. The frozen quiet of winter had gradually melted into a symphony: the chirps, twitters and whistling of song sparrowstheir looped call and response providing a backdrop to the trilled oboe call of loons. The ek ek ek ek of magpies and the staccato drumming of a woodpecker beckoning its life mate. Pussy willows became catkins, gradually giving way to untried leaves.

Joseph watched as a mini-iceberg drifted past, bobbing and shifting in the middle of the river where the current was swiftest. At sixteen, he was an astute paddler who understood the danger these glacial remnants represented for scows or canoes. Only about a third of the ice mass was above the agitated water; the bulk of it lurked below the surface, and if your boat struck that part, it was all overeverything was lost and anyone in the boat would surely drown. Joseph had had a few close calls. Boat, horseback or dogsledthose were the three ways to get to his territory, situated around Lesser Slave LakeAyahciniyiw saakahikan.

After two weeks of torrential rain, the turquoise sky was vast and calm, but Joseph knew this wouldnt last. Before the rainy weather set in, his family had survived a violent windstorm. He and his closest cousins had been out on the land scouting for gooseberries when a sudden silence fell. The birds had hushed and the animals had taken cover in their dens, or wherever they could find it. The young Nehiyawak froze where they stood. Within minutes, the wind whipped up, bending tall aspen trees over as if they were tender willows, snapping some off at the top. Joseph had ducked into a copse of tamarack trees to avoid flying branches and debris, motioning for his cousins to follow him.

Astamitik, kwee ah hu, he yelled.

Now, as miyoskamin unfolded, more Moniyawak appeared on the river, using oars, poles, small sails or some combination of these in their quest to find treasure. Even a haul of a few small gold nuggets seemed worthwhile to them. What joy could a lump of cold shiny metal bring to anyone? The Nehiyaw elders were troubled by the increasing presence of the blond strangers, and Joseph was too.