Contents

Guide

To my parents, Judy and Bruce

and my friend Martha

Contents

A Deployment of Fashion

In Australia, a lone woman

is being crucified by the Press

at any given moment.

With no unedited right

of reply, she is cast out...

... she goes down, overwhelmed

in the feasting grins of pressmen, and Press women...

It is done for the millions.

Sometimes the millions join in

with jokes: how to get a baby

in the Northern Territory? Just stick

your finger down a dingos throat.

Most times, though, the millions

stay money, and the jokes

are snobbish media jokes:

Chemidenko. The Oxleymoron.

Spittle, like the flies on Black Mary.

After the feeding frenzy

sometimes a ruefully balanced last lick

precedes the next selection.

Les Murray, 1997

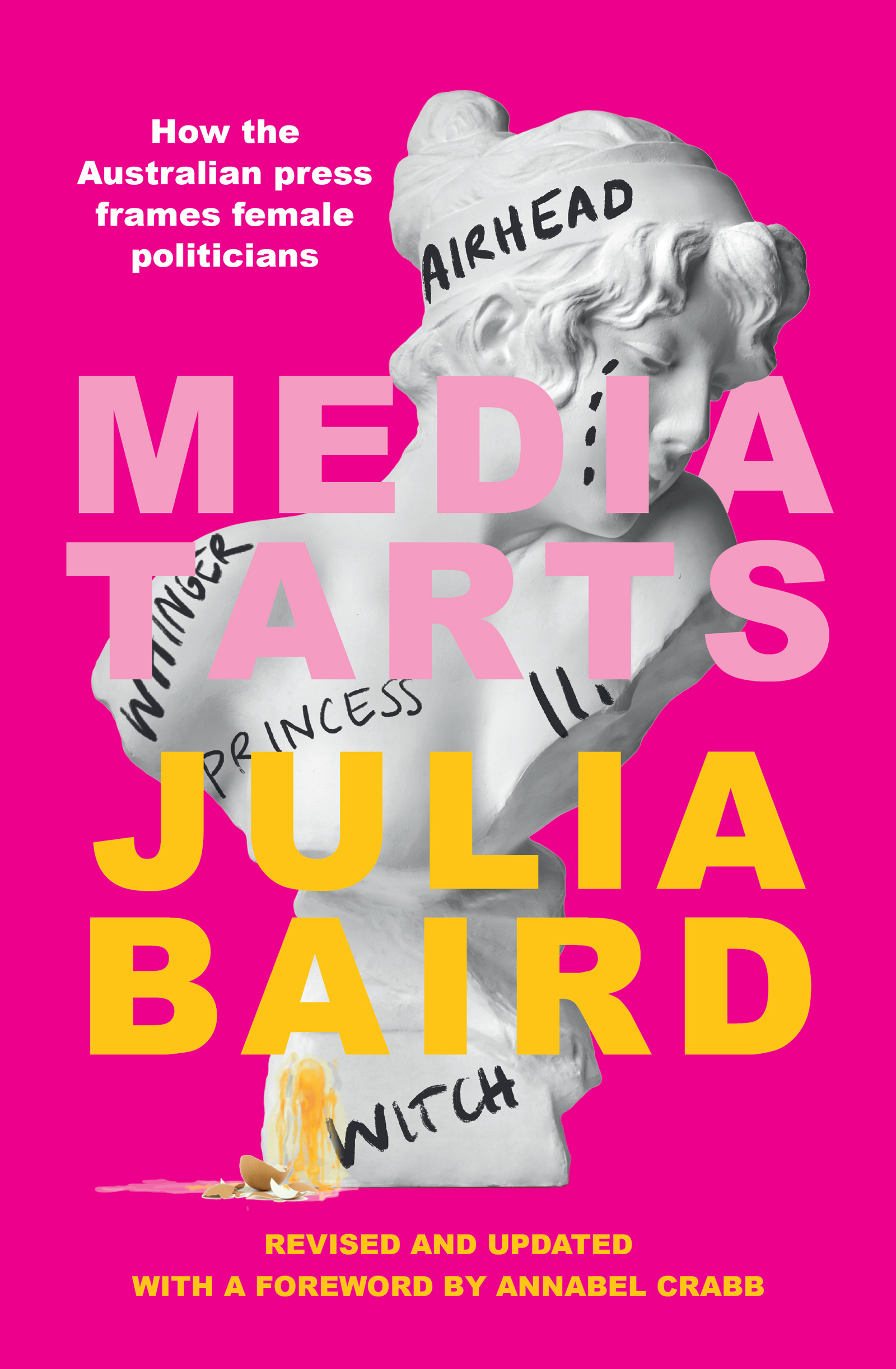

Rereading Julia Bairds seminal book Media Tarts gives me two distinct feelings. One is admiration nearly two decades after it was first published, this book still stands up well. The other is depression, because the reason it still stands up well is that the issues Media Tarts documents for women in parliament havent gone away.

Since its publication, of course, women have made astounding inroads. Theres been a female prime minister, a female governor-general, two female foreign ministers, two female defence ministers, and a mounting horde of female MPs who have managed the juggle of young children with parliamentary careers in a way that still seemed exotic in 2004. Baird, who charted the shocking experience of Ros Kelly in 1983 when she became the first federal MP to give birth while in office, cannot but be heartened, one assumes, by the baby boom of recent years, including the talented young Labor MP Anika Wells who in the plague year of 2020 welcomed twins.

Theres been a fleet of female premiers so many that they have ceased to be particularly unusual though new inductees into this league still run the risk of vapid media coverage like the sort afforded to Lara Giddings by the Australian in 2011. Under the front-page headline Leftist Lara Still Looking For Mr Right, the first paragraph of the news story announcing Ms Giddingss elevation to the premiership read: Lara Giddings says she still hopes to meet the right man but for now shes happy to give all her time to being Tasmanias first female Premier.

The occasional facepalm moment notwithstanding, progress has unquestionably been made.

And yet, in early 2021, we witnessed a spectacular eruption of what has lain beneath, all these years. The volcanic emergence of Brittany Higginss story of alleged rape in the ministerial wing of Parliament House has redrawn the political landscape. Female politicians and staffers have begun to talk about episodes and experiences they had erstwhile kept secret.

For a building in which the Sex Discrimination Act was created drafted and propelled through the Hawke cabinet and then the parliament by the late Susan Ryan, who was at the time the only woman at the cabinet table it appears that the parliament harbours an extraordinary subculture of sexist behaviour and harassment.

Its been shocking, particularly for those who have addressed themselves to the numbers task of getting women elected to parliament, trusting that equal representation would bring its own reward of a fairer and more balanced culture in parliament.

What has become clear is that for women, getting into parliament is one step. Being heard and respected once youre there is another. And the first does not presuppose the second.

*

The year 2021 marks the centenary of Edith Cowans election. In March 1921, she became the first woman elected to any Australian parliament when she won the seat of West Perth in the WA parliament.

She was treated differently from day one, as you can imagine. There was no toilet for her in the building (she had to duck home when nature called). The long-held tradition of listening to the maiden speech of a new MP in courteous silence was in Ediths case not observed. She was interrupted and jeered more than a dozen times.

To honour Ediths anniversary, I set about interviewing some of Australias surviving female political firsts for an ABC documentary series reflecting on the experience of parliament for women over the century. These interviewees came from a variety of party backgrounds and eras. But the one thing almost all of them had in common was this observation: when they found themselves in a meeting with lots of men, they noticed that their ideas would sometimes be ignored, only to be picked up with enthusiasm once a man repeated them. We found archival footage of Nancy Buttfield (the first female senator from South Australia, elected in 1955) remarking upon this phenomenon, and a chorus of current and former female parliamentarians echoed her observations in arrestingly similar terms. Everyone from Julia Gillard to Sarah Hanson-Young to Bronwyn Bishop said the same thing.

How extraordinary that the experience of finding oneself somehow inaudible in a room was so common that women joked about it regularly between themselves.

This question of audibility is a central one. The woman who is ignored in a committee meeting and the woman who chooses not to speak about being sexually assaulted for fear of losing her career are deeply connected. Theyre responding to the same culture. Its a culture that prizes mens experience over womens, that listens out for mens voices and erases womens.

But its changing. The courage of a new cohort of young women who refuse to shoulder a burden of guilt and shame that does not belong to them, plus the influence of senior female journalists who do not minimise the significance of sexual harassment and assault, have created a new age of audibility for women in politics.

Its a perfect time to revisit Media Tarts, which is almost an oral history of women in the parliaments of Australia; a conversation between women across party lines and across the generations that is only now becoming audible to a wider audience.

Julia Baird herself a young journalist when she conducted these interviews and compiled the book has matured since its publication into one of Australias most thoughtful and erudite writers on gender. Her warmly perceptive style is evident throughout the work, coaxing recollections from female MPs about details of their professional lives from the relatively trivial to the profound.

How often are women in politics asked in depth about gender? Most are familiar with the handful of questions at the end of an interview; pretty much every woman I spoke to for the ABC series harbours, I know, a deep caution about discussing gender too much, lest her gender become all that people see when they look at her.

Its only when you hear all their accounts together, in a book like this, that the near-unanimity of experience is laid bare. I found Media Tarts striking and instructive when first I read it. In a new era of attentiveness to womens experience, let its new iteration fire the pistons of change.

Annabel Crabb

May 2021

Lava flows slowly. Following an eruption, a burning mass of melted rock can snake down slopes, hills and streets for months, steadily glowing red, quietly devouring anything in its path. It cannot be controlled, hurried or hushed. It can only be respected, as molten earth should be, and allowed to run its course.

This is what I saw when I stood on the fringe of the crowds at the Womens March 4 Justice in Sydney in March 2021, taking notes with my teenage daughter by my side.

Next page