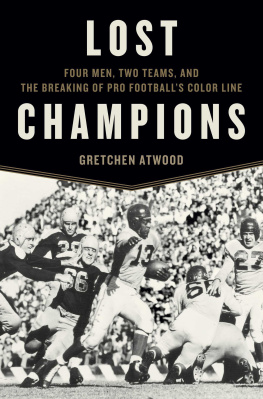

Lost Champions

In honor of

the many pioneering athletes and activists in this book;

those who came before and

those who will follow

Contents

The most common question people asked me when I was working on this book was, What made you decide to write about this? My answers were almost always based on what they meant by this.

If its regarding the integration of pro football, the answer is easy. Years ago I helped my then girlfriend move to Atlanta, Georgia. I was sitting in her living room, surrounded by boxes, thumbing through Americas Game by Michael MacCambridge. I stumbled upon the brief mention of the signing of Kenny Washington and Woody Strode by the Los Angeles Rams in the spring of 1946.

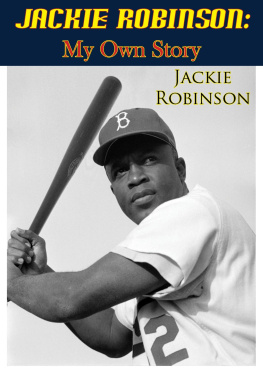

Wait, what?! was my first thought. Nineteen forty-six? I had always assumed that I knew little about the men who integrated modern pro football because they must have come after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947. Everyone knows about Robinsonthe books, movies, his retired jersey number, etc. He was the first, therefore he gets the lions share of public attention and accolades.

But this was telling me he wasnt the first to integrate professional team sports. Sure, baseball was more popular than football then, but that would explain why we know more about Robinson, not why we know very little about the others. It also revealed that I, a former sportswriter with a deep interest in sports, social justice, and twentieth-century American history, was woefully uninformed about this important facet of American sports history. Thus began my journey to answer the question If these guys came before Jackie, why do we know so little about them? This book is my answer.

The second meaning of the query, What made you decide to write about this? is why would I, a white person, write about black history? Its generally not asked with the intent to say that I shouldnt even try, but with the timeworn weariness that it often ends badly, with the stories told through an unexamined cultural and historical lens that centers whiteness. Kenny Washington, Woody Strode, and many others are not acknowledged as trailblazers precisely because of this lens. As journalist Elliot Jaspin noted, History is what we choose to remember, and choosing to remember the people in this bookand others like themis an attempt to reject the lens that determines who is considered a part of capital-H History.

In my efforts to center the people in the book, their stories, and the stories of the black communities they were a part of, I prioritized black sources. This includes family and friends of the football players, periodical sources such as black newspapers and magazines, oral histories, and additional scholarly works. In many cases the white/mainstream press didnt cover these events or comment on their significance, probably because it was assumed they didnt have any. The black media (newspapers, magazines, newsletters) were the only ones thoroughly covering the civil rights battles of the 1940s. But when multiple sources covered topics or events I was writing about, I prioritized the oral histories of black individuals who were involved or alive at that time, or the coverage of the black press, over other sources.

I cannot say there will be nothing problematic in this book or in how I approached its writing. I examined my choices constantly and reviewed them with others to see where I might be bringing my own subconscious biases. I imagine some are still there, despite my efforts, and I take full responsibility for everything on these pages. I am open to feedback from readers who feel Ive committed the same mistakes that I seek to criticize. I can be reached at gretchenatwood@gmail.com. I cant promise Ill reply to all e-mails, but I will give them my full consideration.

A note on language and word choices: If people preferred specific labels, those are what I used for them. When talking more generally about white people or black people, those are usually the terms I use, along with African American. Several individuals expressed a strong preference for black over African American, and I made sure to use that label when referring to them individually or as part of a larger group.

I dont write out the N word in my book. I do use the term Negro when quoting a source from the time Im writing about. I dont use the mascot names for the Washington, D.C., pro football team or the Cleveland pro baseball team. The only time I use Indian is when quoting someone who is Native American or First Nations or they themselves are quoting someone who is and is using the term. All of the conversations and interactions I describe in the book happened, or sources reported they did. I took some liberties to imagine the exact wording of conversations that were not caught verbatim, but that is the extent of my creative license.

Writing this book has led me to a better understanding of so much more than I ever imagined and led me to meeting some of the most amazing people. For that, and them, I will always be grateful.

San Francisco, 2016

Downey Avenue Playground

Los Angeles, California

1925

Kenny Washington watched the white men chuck a frayed baseball back and forth. Bats clattered out of a burlap sack while one man motioned players to fan out across the diamond. Even at six years old, Kenny knew the sport. Blue Washington, his father, had barnstormed with some of the best Negro league teams in the country, pitching for the Chicago American Giants and playing first base for the Kansas City Monarchs. Kenny had previously seen this local, white semipro team play at the Downey Avenue Playground, just two blocks from his house.

The Los Angeles River gurgled immediately west of the park, and the chaparral-studded foothills bobbed along the eastern horizon. The playground formed the western edge of Lincoln Heights, a neighborhood northeast of downtown. Originally the area was home to wealthy families, but as the neighborhood industrialized, those with money moved farther west and left Lincoln Heights to the immigrants who drove the trains and maintained the railroads.

The baseball players Kenny Washington watched were sons and grandsons of these railroad men. As was Kenny, whose grandfather was a cook on the trains and who later ran a mess tent for miners working in the nearby San Gabriel Mountains. The Washingtons were likely the only black family in the neighborhood at the time, and Kenny the only African American kid the ballplayers had seen at the park.

Hey, boy, the teams coach called to Kenny. Were about to start practice. Do you want to chase down the balls and throw them back?

Washington said yes.

He ran to where the coach had pointed, an unhooked strap of his overalls dancing against his back. As Kenny skipped sideways into position, the batter connected with the pitch. Kenny ran after it. He was knock-kneed, and from head-on or behind, his legs formed a skinny X when he ran. But he was so fast that his gait looked fluid despite the odd angles. Kenny swooped onto the ball, hurled it toward the infield, and immediately set himself for the next one.

Batter after batter took his turn. Washington tracked down each ball and flung it back. The coach watched the kids throws, which were reaching the infield on the fly. How far could this youngster throw? He waved for Kenny to stand deeper in the outfield. If anyone had thought about it, they might have suspected Washington was older than he looked. But they didnt. The players continued to swing, the gray balls sliced into the outfield, and the coach motioned Kenny back even farther.