Carl Zimmer

The Free Press

New York London Toronto Sydney Singapore

PARASITE

REX

Inside the Bizarre World

of Natures Most Dangerous

Creatures

Also by Carl Zimmer

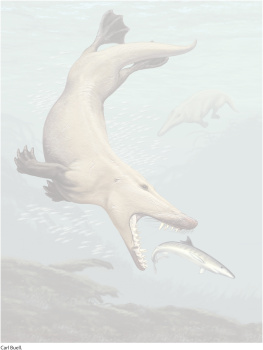

At the Waters Edge: Macroevolution

and the Transformation of Life

THE FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2000 by Carl Zimmer

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

T HE F REE P RESS and colophon are trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Deirdre C. Amthor

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zimmer, Carl

Parasite rex : inside the bizarre world of natures most dangerous creatures / Carl Zimmer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Parasites. I. Title

QL757 .Z56 2000

591.7857dc21

00-037593

ISBN 0-684-85638-7br/>eISBN-13: 978-0-7432-1371-4

ISBN-13: 978-0-6848-5638-4

Thanks to Andreas Schmidt-Rhaesa for the photograph of the nematomorph (photo insert, p.10) originally published in Schmidt-Rhaesa, et al., Journal of Natural History 34 (2000): p. 338, by Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Contents

Prologue: A Vein Is a River

First sightings of the inner world

1 Natures Criminals

How parasites came to be hated by just about everyone

2 Terra Incognita

Swimming through the heart, fighting to the death inside a caterpillar, and other parasitic adventures

3 The Thirty Years War

How parasites provoke, manipulate, and get intimate with our immune system

4 A Precise Horror

How parasites turn their hosts into castrated slaves, drink blood, and manage to change the balance of nature

5 The Great Step Inward

Four billion years in the reign of Parasite Rex

6 Evolution from Within

The peacocks tail , the origin of species, and other battles against the rules of evolution

7 The Two-Legged Host

How Homo sapiens grew up with creatures inside

8 How to Live in a Parasitic World

A sick planet, and how the most newly arrived parasite can be part of a cure

Prologue:

A Vein Is a River

The boy in the bed in front of me was named Justin, and he didnt want to wake up. His bed, a spongy mat on a metal frame, sat in a hospital ward, a small concrete building with empty window frames. The hospital was made up of a few of these buildings, some with thatched roofs, in a wide dusty courtyard. It felt more like a village than a hospital to me. I associate hospitals with cold linoleum, not with goat kids in the courtyard, punching udders and whisking their tails, not with mothers and sisters of patients tending iron pots propped up on little fires under mango trees. The hospital was on the edge of a desolate town called Tambura, and the town was in southern Sudan, near the border with the Central African Republic. If you were to travel out in any direction from the hospital, you would head through little farms of millet and cassava, along winding paths through broken forests and swamps, past concrete-and-brick funeral domes topped with crosses, past termite mounds shaped like giant mushrooms, past mountains covered in venomous snakes, elephants, and leopards. But since youre not from southern Sudan, you probably wouldnt have traveled out in any direction, at least not when I was there. For twenty years a civil war had been lingering in Sudan between the southern tribes and the northerners. When I visited, the rebels had been in control of Tambura for four years, and they decreed that any outsiders who arrived on the weekly prop plane that landed on its muddy airstrip could travel only with rebel minders, and only in the daytime.

Justin, the boy in the bed, was twelve years old, with thin shoulders and a belly that curved inward like a bowl. He wore khaki shorts and a blue-beaded necklace; on the window ledge above him was a sack woven from reeds and a pair of sandals, each with a metal flower on its thong. His neck was so swollen that it was hard to tell where the back of his head began. His eyes bulged in a froglike way, and his nostrils were clogged shut.

Hello, Justin! Justin, hello? a woman said to him. There were seven of us there at the boys bedside. There was the woman, an American doctor named Mickey Richer. There was an American nurse named John Carcello, a tall middle-aged man. And there were four Sudanese health workers. Justin tried to ignore all of us, as if wed all just go away and he could go back to sleep. Do you know where you are? Richer asked him. One of the Sudanese nurses translated into Zande. He nodded and said, Tambura.

Richer gently propped him up against her side. His neck and back were so stiff that when she lifted him he rose like a plank. She couldnt bend his neck, and as she tried, Justin, his eyes barely open, whimpered for her to stop. If this happens, she said emphatically to the Sudanese, call a doctor. She was trying to hide her irritation that they hadnt called her already. The boys stiff neck meant that he was at the edge of death. For weeks his body had been overrun with a single-celled parasite, and the medicine Richer was giving him wasnt working. And there were a hundred other patients in Richers hospital, all of whom had the same fatal disease, called sleeping sickness.

I had come here to Tambura for its parasites, the way some people go to Tanzania for its lions or Komodo for its dragons. In New York, where I live, the word parasite doesnt mean much, or at least not much in particular. When Id tell people there I was studying parasites, some would say, You mean tapeworms? and some would say, You mean ex-wives? The word is slippery. Even in scientific circles, its definition can slide around. It can mean anything that lives on or in another organism at the expense of that organism. That definition can include a cold virus or the bacteria that cause meningitis. But if you tell a friend with a cough that hes harboring parasites, he may think you mean that theres an alien sitting in his chest, waiting to burst out and devour everything in sight. Parasites belong in nightmares, not in doctors offices. And scientists themselves, for peculiar reasons of history, tend to use the word for everything that lives parasitically except bacteria and viruses.

Even in that constrained definition, parasites are a vast menagerie. Justin, for example, was lying in his hospital bed on the verge of death because his body had become home to a parasite called a trypanosome. Trypanosomes are single-celled creatures, but they are far more closely related to us humans than to bacteria. They got into Justins body when he was bitten by a tsetse fly. As the tsetse fly drank his blood the trypansomes poured in. They began to steal oxygen and glucose from Justins blood, multiplied and eluded his immune system, invaded his organs, and even slipped into his brain. Sleeping sickness gets its name from the way trypansomes disrupt peoples brains, wrecking their biological clock and turning day to night. If Justins mother hadnt brought him to the Tambura hospital, he would certainly have died in a matter of months. Sleeping sickness is a disease without pardon.

Next page