Paris and the Parasite

Paris and the Parasite

Noise, Health, and Politics in the Media City

Macs Smith

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Macs, author.

Title: Paris and the parasite : noise, health, and politics in the media city / Macs Smith.

Other titles: Paris and the parasite (M.I.T. Press)

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2021] | Outgrowth of the authors thesis (doctoral)Princeton University, 2018, under the title: Paris and the parasite : the politics of noise in the mediatic city. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020022995 | ISBN 9780262045544 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: City planningFranceParis. | Architecture and societyFranceParis. | ArchitectureHuman factorsFranceParis. | Parasitism (Social sciences)

Classification: LCC NA9198.P2 S55 2021 | DDC 711/.40944361dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020022995

d_r0

For my mother, who taught me that a healthy body doesnt mean anything, that love is what matters

Contents

I completed this book while under lockdown because of Covid-19. When I had to leave my room in Oxford, my partners family took me in, not knowing how long my stay would be. In the end, I spent over one hundred days in their home. I am conscious of how much hospitality has been shown me since I began work on this project seven years ago.

Paris and the Parasite emerged from my doctoral research at Princeton University. The people who shaped and nurtured my development as a scholar all contributed to it in some way. This book would not exist were it not for Andr Benham. Andr was the first person to ask me if I thought absolute hospitality was something you could practice or something hypothetical. His mentorship is the best argument for the former. Gran Blix, Katie Chenoweth, and Tom Levin gave me excellent feedback and encouragement. I especially want to thank Tom and Joseph Vogl for introducing me to McLuhan and Serres. I am grateful to Princeton University for generously supporting my work, and for its faith in and financial commitment to the creative power of its students and researchers. Thank you to the Department of French and Italian, the School of Architecture, and the Program in Media + Modernity for giving me a home and for fostering interdisciplinary research. I am indebted to Charlotte Werbe, Chad Crdova, Melissa Verhey, Emily Eyestone, Hartley Miller, Sarah Kislingbury, Molly OBrien, and many others for our conversations and friendship.

The Queens College, Oxford, has provided me a community and the time to write. I am grateful to my colleagues for pushing my thinking in new directions, and to the Hamilton family for their generous support for research in French studies. Thank you to Seth Whidden, Jessica Stacey, and Holly Langstaff in particular. Additionally, thank you to Sophie Marnette and Michael Sheringham for facilitating my first research visit to Oxford, and to Emma Claussen, Gemma Tidman, Olivia Tolley, and Sarah Jones for making me want to return.

Thank you to the MIT Press, particularly to Doug Sery and Noah Springer, and to my copyeditor, Gillian Beaumont. My peer reviewers provided insightful comments that significantly improved this book. Thank you to all of my students, who inspire me with their courage, their vulnerability, and their determination to bring beauty into the world. Thank you to Julian, Celia, and Owen Iredale for welcoming me into their home. Thank you, Hope and Henry. And lastly, Ellen, I love you even more than Paris.

In February of 2016, the municipal government of Paris published a Plan de prvention du bruit dans lenvironnement, or Plan for the Prevention of Noise in the Environment (PPBE). The document opens with two observations: first, that polls have shown growing levels of concern about noise among Parisians; and second, that noise represents the second-most-important environmental influence on human health after air pollution. The document lays out a five-year plan consisting of 39 measures to quiet the soundscape of the city. The PPBE acknowledges that the line between sound and noise is fuzzy. Noise is subjective. It is one persons experience of a sound at a given moment. Music coming through the wall from my neighbors apartment is sound if Im in a mood to listen to it, and noise if Im not. Traffic, birdsong, and voices in the street might be perceived as pleasant signs of a vibrant city, or they might not. There is nothing in the soundwaves themselves that can tell us how a sound will be perceived by a listener. Parisians might be increasingly worried about noise, but what each of them thinks of as noise might be different. By stating this, the PPBE undermines its premise right from the start. If there is no objective definition for noise, then what is there to regulate? If the meaning of noise can change for a given person from moment to moment, then the government seems to be taking on the task of imposing a normative aesthetic standard on the urban soundscape and policing citizens personal experience of it.

The PPBE dodges this trap by turning to the International Organization for Standardization, which defines noise according to the sensation it produces. That word can be interpreted physiologically as well as emotionally, opening up the possibility of an objective definition of noise based not on the listeners mood or artistic tastes but on the effect the sound has on their body. A sound can therefore be defined as noise if it harms the listeners body in a detectable way.

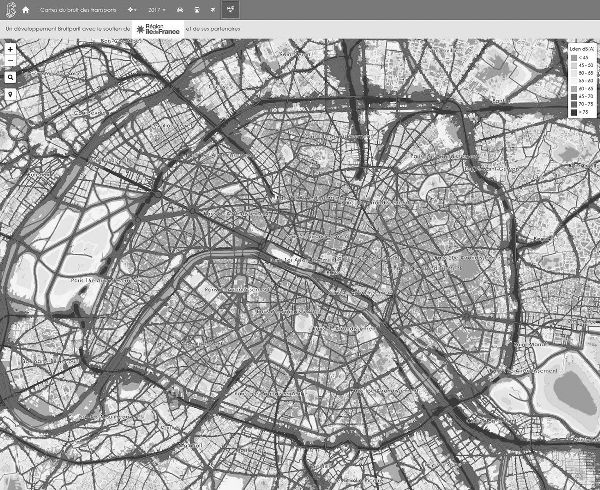

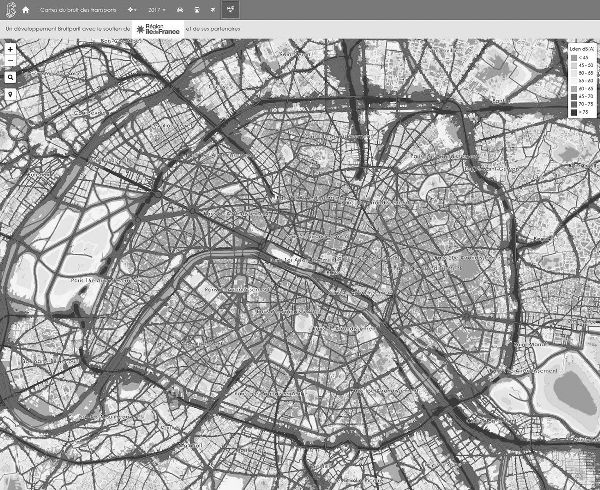

Figure 1.1

Noise map of Paris created by Bruitparif (www.bruitparif.fr)

With this definition in hand, the PPBE proceeds to argue that noise is a health issue and, indeed, that Paris is experiencing a public health crisis. Noise, the report states, raises stress levels, worsens cardiovascular health, and interrupts sleep, leading to a host of secondary health issues. Playing up the environmental part of its title, the PPBE repeatedly ties noise to air pollution, saying that vehicles that emit less CO2 also emit less noise, and comparing the quiet of green spaces and parks to the clean air the trees provide. Readers are led to assume that reducing noise in the city will also indirectly benefit their lungs. In interviews conducted after the release of the report, Clia Blauel, the adjointe to the mayor in charge of the environment, cited the statistic that 10,000 deaths in Paris per year are caused by noise. Beyond questions of comfort and quality of life, she said, the acoustic environment constitutes a public health concern.

Public health is not the only reason to care about urban noise. Noise also has a sociopolitical dimension, according to the PPBE. It is an important factor in social segregation as the rich buy homes in quiet neighborhoods while the poor are exposed to harmful soundscapes, disadvantaging them for life. How the government proposes to manage noise likewise directly concerns the social politics of the city. Many of the suggested interventions center around the commute, and in particular how residents of the

Next page