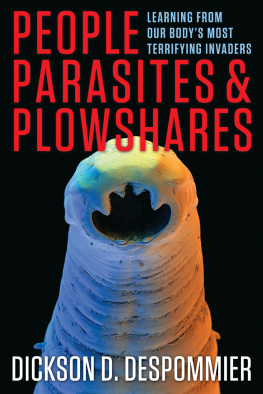

People, Parasites, and Plowshares

ALSO BY DICKSON D. DESPOMMIER

West Nile Story (New York: Apple Tree Productions, 2000)

Parasitic Diseases (5th ed., New York: Apple Tree Productions, 2005)

The Vertical Farm (New York: St. Martins Press, 2010)

People, Parasites, and Plowshares

Learning from Our Bodys Most Terrifying Invaders

DICKSON D. DESPOMMIER

Foreword by William C. Campbell

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Dickson D. Despommier

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-0-231-53526-7 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Despommier, Dickson D.

People, parasites, and plowshares : learning from our bodys most terrifying invaders / Dickson D. Despommier ; foreword by William C. Campbell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16194-7 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-53526-7 (ebook)

1. ParasitesPopular works. 2. Host-parasite relationshipsPopular works. 3. Parasitology. I. Title.

QL757.D47 2013

578.65dc23

2012050589

COVER PHOTO: David Scharf Getty Images

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

O! your parasite

Is a most precious thing...

BEN JONSON (1607)

No less a genius than Alfred North Whitehead was of the opinion that one is unlikely to have new ideas after the age of 60, but one can still make good use of the ideas one already has. It is no secret that Dr. Dickson Despommiers genius has been more than sixty years in the making, yet in his conversation new ideas burst forth like bullets from a machine gun. Many of his friends have experienced the phenomenon firsthandan experience that his former colleague Dr. George Stewart has referred to as being dicksonized. The book People, Parasites, and Plowshares, however, epitomizes the other half of Whiteheads assertion. Over the years, Despommier has written much that is addressed to professional colleagues in medicine and the biomedical sciences; now he aims to share his knowledge of parasitology with the general reader. His knowledge is vast and his aim is true. The result is a work that is eminently instructive as well as being fun for the reader and (quite evidently) for the author. But that is not the only reason that his writing of this book has been a worthwhile endeavor.

Other disciplines, besides parasitology, bring special techniques and insights to the study of parasites, and from them we learn subtle secrets that can be uncovered only by biochemistry, pathophysiology, immunology, and many other branches of science. So, by steps big and small, our understanding of parasitism is constantly enriched. Despommier teaches us the basic elements of medical parasitology (drawing on his long and much acclaimed tenure on the professorial podium) but also brings to the pages of this book a treasure of the latest advances in the most arcane and up-to-date areas of research. These advances he integrates artfully into his narrative along with bold and plentiful speculation as to their promise or lack of promise in practical affairs. Those of us who exceed the Whitehead boundary by an even wider margin may rub our eyes in astonishment, even bewilderment, but young readers will relish this feast of informationand many, we may hope, will be inspired by it. In this context it may be worth noting the value of introducing young students to medical parasitology for they are already exposed to modern scientific concepts and, besides, they tend to have a natural affinity for the grotty kind of visual image that medical parasitology produces in such profusion.

Though parasitology is not an endangered discipline, parasitologists sometimes worry that they are becoming an endangered species. This is because hordes (and I use the word respectfully) of scientists do research on parasites day in and day out, while a smaller and smaller proportion of them come up through the traditional avenues of training and confraternal bonding that mean so much to those of us who are old-school parasitologists. Such institutional evolution engenders a trace of forebodinga worry that interest as well as expertise is fragmenting, thereby constricting the reach of parasitology as an academic fellowship. Eventually the expanding and splintering disciplines of science may collapse into a dense mass of physics; but that is hardly imminent. For now, a book like People, Parasites, and Plowshares is just the sort of tonic we need.

To this day, the traditional sort of parasitology often comes up with startling new findings. The worm Onchocerca volvulus, which causes river blindness, is itself parasitized by bacteria. (I like to imagine, just for fun, that Shakespeares Prospero had Onchocerca in mind when he exclaimed, Poor worm, thou art infected!) Only recently has it been recognized that the bacteria in the worms play a role in causing the actual signs and symptoms of the human disease. While the clinical manifestations are bad enough, the social consequences add greatly to the misery of affected populations. I have known about river blindness since I was a student and have seen its ravages in sub-Saharan Africa, yet never have I seen so graphic an account of its social impact as in the pages of this book. (Inclusion of such vignettes is one of the bonuses the book provides.) For well over a century, the tiny roundworm Trichinella spiralis has been known to cause trichinellosis (trichinosis) in humans and to live in the flesh of pigs. Traditional methods have also shown that the worm exists in many warm-blooded animalsand even in the coldblooded crocodileand that the Arctic can boast a Trichinella species that can survive for many months in frozen meat! Studies in molecular and evolutionary biology have elucidated the many different species and strains that make up this epidemiological complex, while other new methods have vastly increased our knowledge of the basic biology of the parasite. (Despommiers own contributions to our understanding of Trichinella have been pioneering and numerous.) For parasitology in general, it is safe to say that both the old and the new sciences will provide challenge and delight (and income) into the indefinite future.

Despommiers book, as its title tells, is about people. We can hope that readers, once hooked by these tales of human travail and attendant scientific exploration, will look further into the vast world of organisms that parasitize hosts other than human beings. Unless they do that, they are likely to forfeit the pleasure of knowing that there is a tiny flatworm, Oculotrema hippopotami, that lives in the eye of the host from which it gets its species name. That, of course, must seem a trivial matter (except, perhaps, to the parties involved), and indeed it counts for little in the context of parasitism and human affairs. But while there may have been a little truth in Popes old aphorism that the proper study of mankind is man, there is a very large truth in the thought that the interest and concern of humans should extend to the creatures that share our planet, including those that we have domesticatedand of course their parasites. The price of a chicken dinner is determined largely by a single-cell parasite; the softness of our woolen sweater is affected by a whole suite of roundworms; and the durability of our leather shoes is diminished by parasitic larvae of insects. As long as people are omnivorous or carnivorous, the roundworms of cattle will (indirectly) be of greater importance to people than will the roundworms of people. And then there are the parasites of plantsincluding the parasites of the plants that nourish the cattle that nourish the people. Writer Carl Zimmer eloquently makes the point that parasites are in many ways drivers of organic evolution. Their relevance to our world may indeed be infinite! Despommier is well aware of these beyond-human realms of parasitology. Perhaps someday he will write a book about them. In the meantime we can relish his lively discourses on parasites, people, and places.

Next page