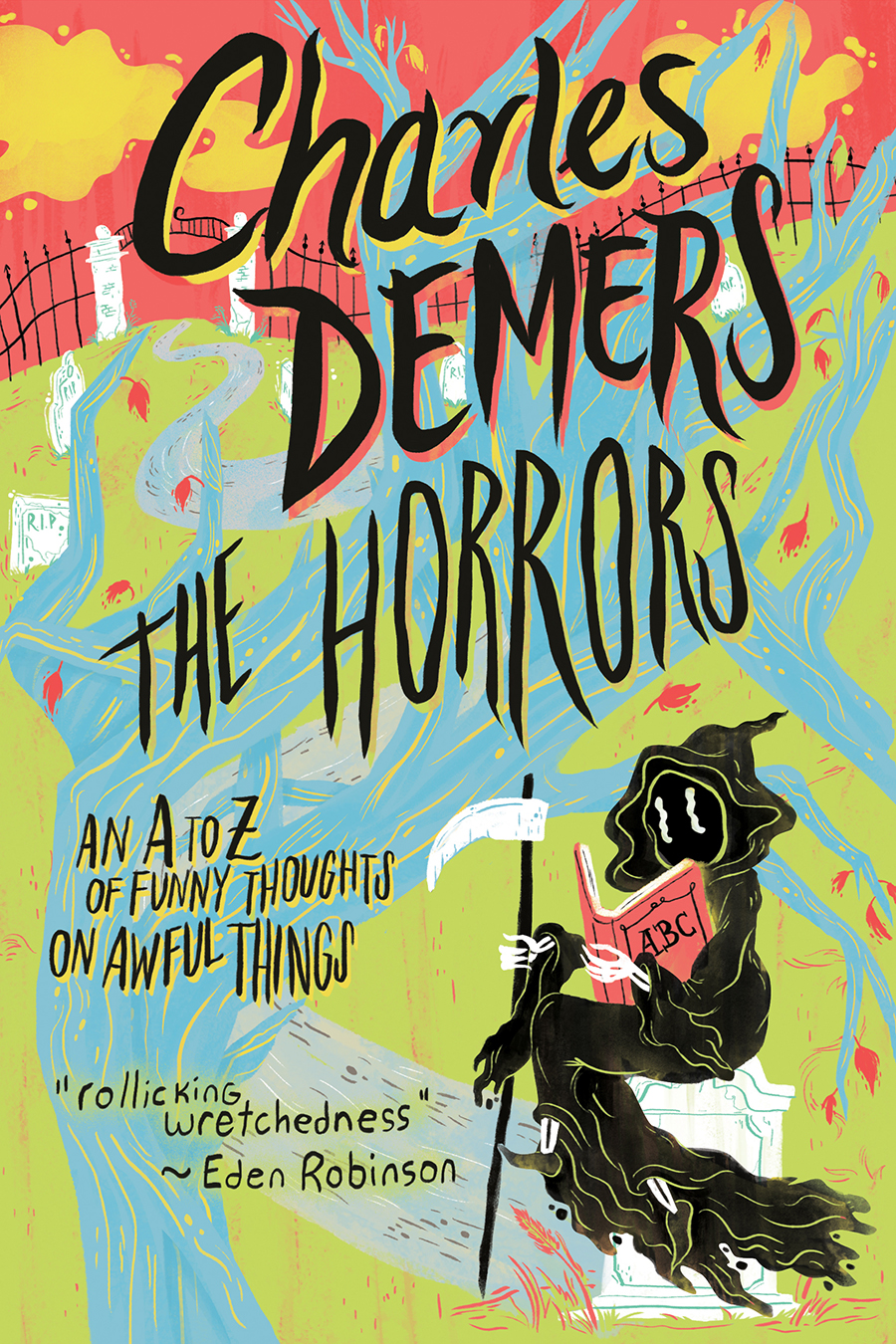

The Horrors

Copyright 2015 Charles Demers

1 2 3 4 5 19 18 17 16 15

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, .

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Cover and interior illustrations by Eduardorama

Edited by Trena White

Cover design by Carleton Wilson

Text design by Carleton Wilson

Printed and bound in Canada on FSC -certified 100% post-consumer fibre

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $157 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77162-031-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-1-77162-032-1 (ebook)

For my father, Daniel Demers, whose unshakably

positive outlook on life has been my

only reason for ever questioning his paternity.

Je taime fort, fort.

Tragedy, like its partner comedy, depends on an acknowledgement of the flawed, botched nature of human lifealthough in tragedy one has to be hauled through hell to arrive at this recognition, so obdurate and tenacious is human self-delusion. Comedy embraces roughness and imperfection from the outset, and has no illusions about pious ideals. Against such grandiose follies, it pits the lowly, persistent, indestructible stuff of everyday life.

Terry Eagleton

That there exists a sometimes infinitesimally short circuit connecting pain to humour is one of the elemental facts of my life, a lesson laid down in the first few minutes of my existence: while the doctor was stitching my mothers torn perineum in the maternity ward, Mom turned to the medic and deadpanned: Might as well stitch it all the way up, docnobodys getting back in there.

My mothers side of the family, the Birnies, have always been good at rattling off one-liners to let you know when theyre hurting, even if the jokes come out by accident. When my auntie Laurie was asked, just a few months into her marriage and already frustrated with her husbands overwhelming focus on hockey, Hows married life? she replied, without intending any wordplay: Its fine, in between periods. (I was heartbroken when a terrible version of this same joke appeared on the execrable David Spade sitcom Rules of Engagement; it was like finding out that Guy Fieri had gotten his hands on an old, beloved family recipe, then battered the results in Cool Ranch Doritos.)

The Birnie family has always moved with ease between tragedy and comedy. My uncle Phil could easily have been a professional comic, and the same was often said about my hilarious mom; people were, Ive been told, constantly telling her that she should be on The Carol Burnett Showa compliment she couldnt fully process as one because, inexplicably, she hated The Carol Burnett Show. Nevertheless, she was funny enough, plus she was redheaded. A lifetime of family get-togethers with cousins and aunts and uncles has run together in my memory as an unending string of jokes, funny anecdotes and recounted pranks, like the time when they were children that my Mom told Laurie, Whatever youre holding comes with you when you die, before grasping hold of her, sputtering, and rolling her eyes back in her head.

The thing is, when family members werent pretending to die, for gags, they were doing it for real, kicking off the litany of traumas that punctuated the punch lines. Ronnie, Moms older brother, is struck by a vehicle and killed at age four; a few years later, her dad, my grandpa, dies at thirty-three from a heart condition, not only plunging the family into fatherlessness but also causing a precipitous drop in socio-economic standing from a family headed by a wealthy, hotshot young lawyer to one led by a widowed mother; at age twenty, the baby of the family, my uncle Chris, is run over by a car while riding his bicycle; three years after that, my mother is diagnosed with leukemia, and she dies a few years later, in the house that my parents, my brother and I share with my granny and auntie Heather, while we are all at home. I am ten years old.

So those are the pitch-black opening credits that roll before the sitcom of my maternal familys life. I see them ending with the Grim Reaper in the role of wacky neighbour, giving the camera a Whaddya gonna do? shrug while a bucket of water or something falls on his head, or he notices one of those pesky Birnie kids has replaced his scythe with a goalie stick.

I think those traumas produced the rapid alternation between grief and laughter that marks my family, and defines them for me. Its probably the way in which I feel most deeply and irrevocably a part of the family, too.

* * *

What can humour do?

Well, who among us can forget the great Smarm versus Snark wars of late 2013? They began when Gawker contributor Tom Scocca wrote a terrific essay defending the snipey, caustically ironic sensibility widely denounced as snark against what he saw as the sententious, self-righteous faux-positivity of the powerful and privileged, identified as smarm. The piece called out bestselling author, speaker and New Yorker essayist Malcolm Gladwell as a prime purveyor of said smarm, so unsurprisingly came in for a strong (and, dare I say it, somewhat smarmy) rebuttal from him. Gladwell cherry-picked quotes from Scoccas piece that made him seem humourless and wildly unpleasant, then proceeded to cite another of the years remarkable essaysthis one a brilliantly argued and thoroughly depressing meditation by Jonathan Coe in the London Review of Books on the limits of political satire. Its not the respectful voice that props up the status quo, wrote Gladwell, channelling Coe, it is the mocking one.

I had read Coes piece, Sinking Giggling into the Sea, when it came out and, as a politically minded comedian, had been winded by it. Id winced through sentence after sentence like the following: Famously, when opening his club, The Establishment, in Soho in 1961, [Peter] Cook remarked that he was modelling it on those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the Second World War. Dude. Fucking ouch, dude.

The question of what humour can and cant do to subvert or protect us from that which terrifies us and oppresses us, in either our political or our personal lives, is an open one. Can a tyranny be toppled in a Chaplinesque pratfall? Or does laughter anaesthetize us against injustice? Can finding humour in the dark corners of our lives give us the strength to confront whats hurting us? Or does it let us run away from our own problems and adopt a callous attitude to those of other people? The answer, as in virtually every cheesy, rhetorical, straw-man dichotomy like the ones Ive just set up, is both and neither.