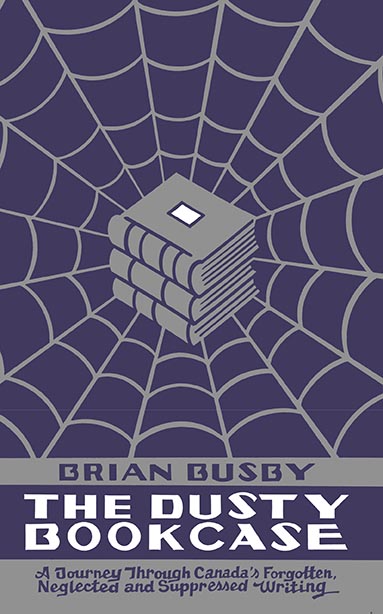

Copyright Brian Busby, 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

FIRST EDITION

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Busby, Brian John, author

The dusty bookcase : a journey through Canadas forgotten, neglected, and suppressed writing / Brian Busby.

Issued also in electronic format.

ISBN 978-1-77196-168-4 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77196-169-1 (ebook)

1. Canadian literature--Miscellanea. 2. Literary curiosa. 3. Canadian literature--History and criticism. 4. Books and reading--Canada--History. 5. Canadian literature--Censorship. 6. Censorship--Canada--History. I. Title.

PS8219.B87 2017 C810.9 C2016-907970-8

C2016-907971-6

Edited by Emily Donaldson

Copy-edited by Allana Amlin

Typeset by Chris Andrechek

Illustrated and designed by Seth

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country, and the financial support of the Government of Canada. Biblioasis also acknowledges the support of the Ontario Arts Council (OAC), an agency of the Government of Ontario, which last year funded 1,709 individual artists and 1,078 organizations in 204 communities across Ontario, for a total of $52.1 million, and the contribution of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

For Stanley Whyte and Chris Kelly

As you know

Introduction

We didnt read Canadian literature in Allancroft Elementary School. The books assigned at Beaconsfield High School were by John Steinbeck, Jack Schaefer, James Vance Marshall, William Golding, John Wyndham, Charles Dickens, George Orwell, Georges Simenon, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. One classnot minegot to read Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan of the Apes .

My introduction to the countrys literature came through scanning the racks at the local Kanes Super Drug Mart. They werent at all difficult to spot. William C. Heines The Last Canadian was obvious. The cover of Bruce Powes Killing Ground promised a novel about The Canadian Civil War. Others had maple leaves somewhere on their covers. This is how I came to read Richard Rohmer, whose Ultimatum , Exxoneration , Exodus/UK , and Separation were bought with money earned delivering our local newspaper. Somehow I discovered that Arthur Hailey was kind of a Canadian. I expect Im one of a small number of people to have tackled all 440 pages of Airport as a pre-teen. Over time, I came to recognize that many of the books I was buying bore the Pocket, PaperJacks, and Seal logos. Using them as my guides, I added Hit and Run by Tom Alderman, Joy Carrolls Satans Bell , and something called Some Canadian Ghosts to my collection.

In tenth grade, my Canadian book buying came to an abrupt stop. Id like to say girls were the reason, but in truth it had more to do with the realization that nothing I read was much good. This confirmed the unspoken lesson learned in school: when it came to writing, Canadians werent worthy of attention. The assigned reading for that years English class included Shane , The Pearl, Walkabout , The Chrysalids and, predictably, Lord of the Flies . Of these, my favourite was The Chrysalids , in part because it takes place in post-apocalyptic Labrador, as opposed to, say, nineteenth-century Wyoming.

Make of that what you will.

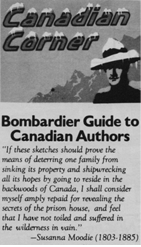

Whatever remaining interest I had in my countrys literature was kept alive through an American magazine, N ational Lampoon , which had just begun publishing something called the Bombardier Guide to Canadian Authors .

Written by Sean Kelly, Ted Mann, and Brian Shein, purportedly with financial assistance from Bombardier, its format was simple: brief entries followed by a rating on a scale of one to five skidoos.

The first to be so honoured was Margaret Atwood (one skidoo). This brief excerpt provides a fair example of the guides style:

She is best known for advancing the theory that America and Canada are simply states of mind, the former comparable to that of a schnapps-crazed Wehrmacht foot soldier and the latter to that of an autistic child left behind in a deserted Muskoka summer cottage playing with Molsons Ale cans, spent shell casings, and dead birds hung from the light fixture, who will one day become aware of its situation, go to college, and write novels. She is better known, among Margaret-watchers, for taking gross offense at the suggestion (in a crudely dittoed literary periodical) that she may have sparked an erection in a considerably more talented Canadian author who shall here remain nameless (see Glassco, John).

That last sentence wouldve been my first encounter with Glasscos name. The incident described is one that demanded particular care when writing A Gentleman of Pleasure , my biography of the man. Rosalie Abella, the lawyer Ms Atwood hired to go after the crudely dittoed literary periodical, now sits on the Supreme Court.

And heres Glassco again in the entry for Callahan [sic] , Morely [sic] (two skidoos):

Callahan, Morely (1903 ) Callahans reputation rests largely upon his memoir of Paris in the twenties, That Summer in Paris , which can almost be put on par with a considerably more talented Canadian authors memories of the same period (see Glassco, John). The other foundation of Callahans repute is a trio of endorsements from Edmund Wilson, Ernest Hemingway, and James Joyce. As for Wilson, who could trust a man known to Unity Mitford as Bunny? Hemingway thought Knut Hamsun was a genius, and with all respect to Joyce, who could take one Irishmans word about another?

The reference source appeared sporadically through 1978, then returned five years later. I was then at university, palling around with two of Sean Kellys kids. It was a coincidence worthy of Isabel Ecclestone Mackay (not covered in the guide). Much more predictable was the presence of Frederick Philip Grove on my reading lists. The magazines April 1983 issue, which marked its return, brought this well-timed entry:

Grove, Frederick Philip (18791948) As a young European aesthete, Grove (or Greve, to use his original German name) formulated an ingeniously decadent plan: to forsake stimulating companionship, rich culture, and the avant-garde of twentieth-century art in order to bury himself in a tedious and meaningless existence as a rural schoolteacher on the Canadian prairies, an existence he was to recount in a series of equally tedious books. His career as a novelist and essayist can thus be seen as a perversely protracted jeu desprite [sic], carried out with an unfortunate combination of Teutonic wit and Canadian flair for the dramatic. But not even Groves dullness was equal to that of his public: when a scene in Settlers in [sic] the Marsh (published in 1925, three years after Ulysses ) vaguely hinted at nocturnal marital activities, denunciations of the novel as pornographic caused a mass of Canadian readers to virtuously refuse to buy, let alone read it, often smuggling themselves out of the country wearing false jackets in order not to be considered found-ins.