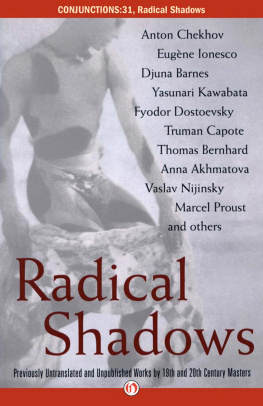

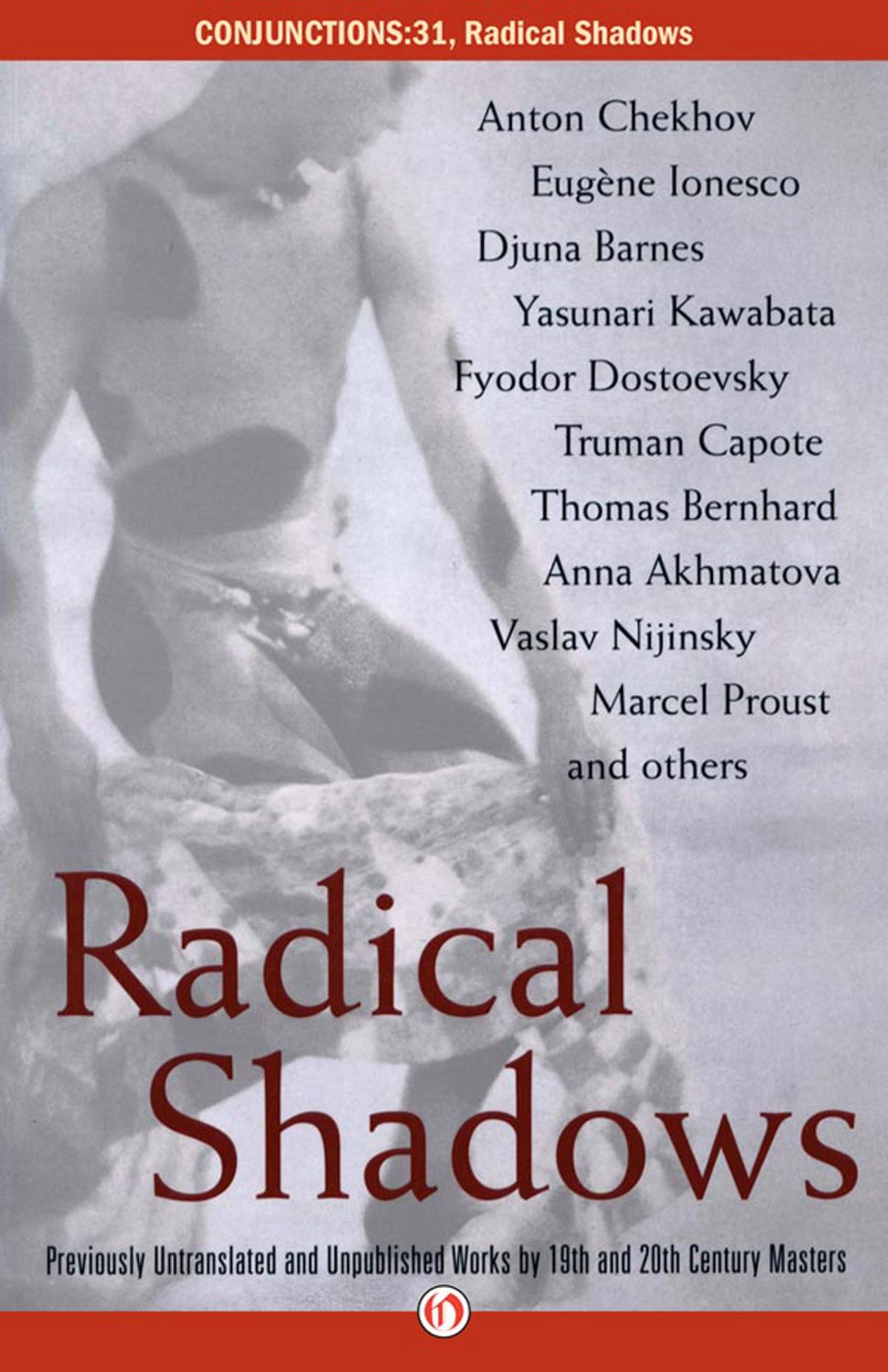

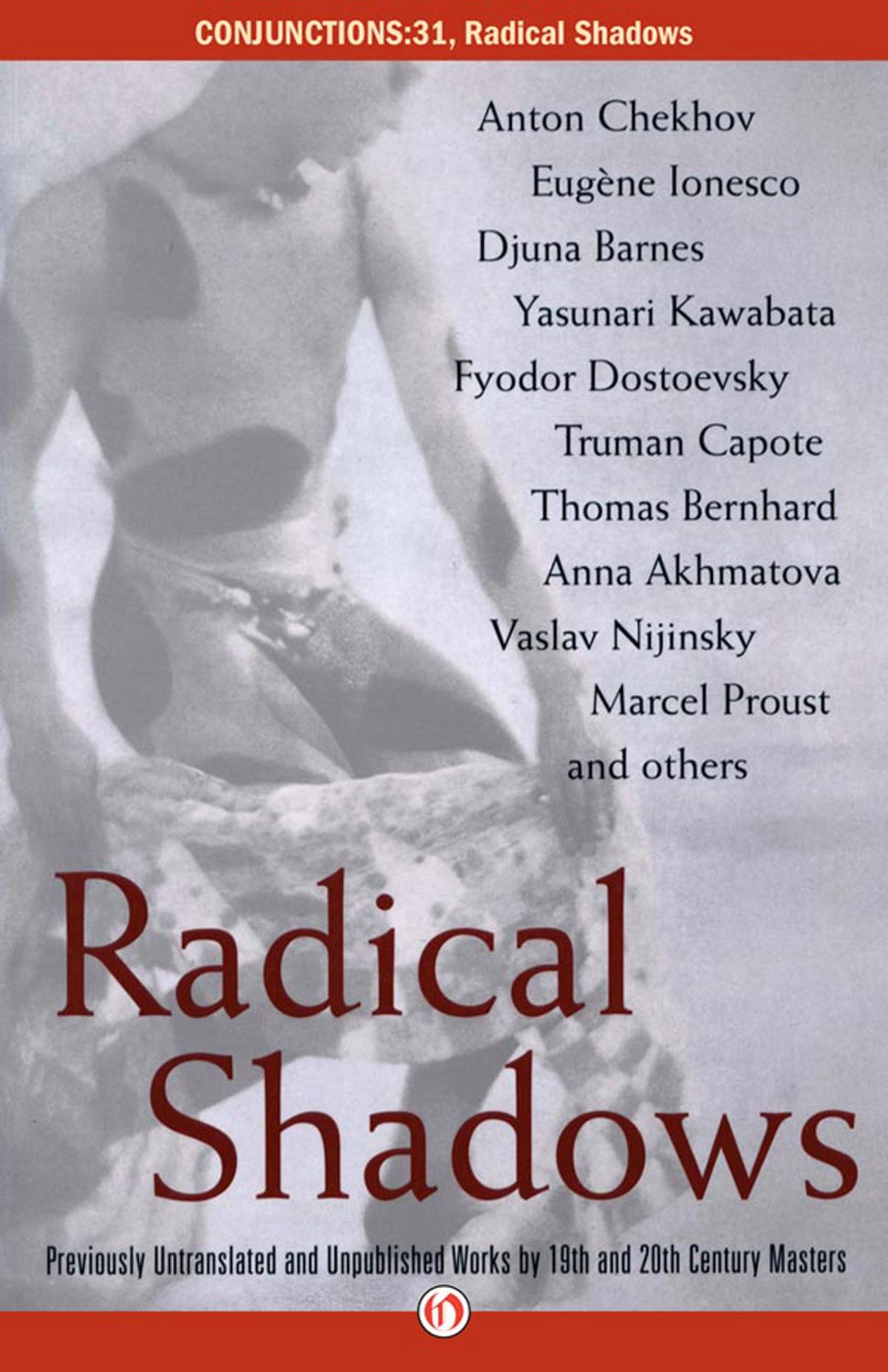

Radical Shadows

Previously Untranslated and Unpublished Works by Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Masters

Conjunctions, Vol. 31

Edited by Bradford Morrow

CONJUNCTIONS

Bi-Annual Volumes of New Writing

Edited by

Bradford Morrow

Contributing Editors

Chinua Achebe

John Ashbery

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

Guy Davenport

Elizabeth Frank

William H. Gass

John Guare

Robert Kelly

Ann Lauterbach

Norman Manea

Patrick McGrath

Mona Simpson

Nathaniel Tarn

Quincy Troupe

William Weaver

John Edgar Wideman

published by Bard College

INTRODUCTION

THIS PROJECT BEGAN AS serendipity, then developed into an international search. Last winter, Joyce Carol Oates wrote me about an acquaintance who had completed work on some previously untranslated stories by Yasunari Kawabatawas I interested in seeing the manuscript? That same week, I happened to be speaking with Peter Constantine, himself a translator of writings from some twenty languages, who offered me a group of short stories by Anton Chekhov that had not yet seen their way into print in English. This set me and Peter, and a host of other friends, on a quest to see if we couldnt uncover works by some major literary writers from the late nineteenth century forward, that were lost, forgotten, suppressed, rare, unknownor, at minimum, unknown in Englishand commission translations or secure rights to bring them into the light.

Why Radical Shadows? As a title for this collection of fiction, poetry, plays and journals written by some of our great nineteenth- and twentieth-century innovative forebearssome undiminished shades of the relatively recent pastRadical Shadows seemed apt. But as a larger idea, one that raises some intriguing questions, Radical Shadows becomes more provocative than I might first have imagined. We who value literature must ask ourselves: What else has been left behind in the mad rush of this frenzied century? What other works remain safe but unexplored in private or institutional archives, or were published in their original languages in ephemeral reviews known only to specialists, or were until recently suppressed by governments to whom certain writers were (and are, in some cases) considered dangerous and thus have languished, out of official critical favor? How much important material has been overlooked? How many works by major writers such as Proust have been published in honorable, but very limited deluxe editions that few but book collectors will have the chance to read? What other texts have come down to us in versions expurgated or altered by members of the authors families, such as in the cases of Vaslav Nijinsky and Antonia Pozzi? If works as interesting as Musils play and Federigo Tozzis stories and Dostoevskys prison passage havent found their way into English until now, what other remarkable literature is out there, unknown to so many readers? How was it that a magnificent poem by Djuna Barnes, once rejected by Marianne Moore when she worked at The Dial, until now remained unpublished along with many of Barness personal favorites, unknown to those among us who like her Jacobean line better than Miss Moore did?

Norman Manea, the great Romanian writer who was kind enough to bring to my attention both the Cioran and delightful Ionesco works in this issue, tells me that his own manuscripts were lost when he had to flee his homeland, and that other of his papers are locked in the censors safebox in Romaniaunavailable not only to his readers, but to the author himself! In a perceptive introduction to a collection of political essays by Gnter Grass some years ago, Salman Rushdie proposed that one of the themes central to all twentieth-century writing is that of the migrant. Rushdie writes, The very word metaphor, with its roots in the Greek words for bearing across, describes a sort of migration, the migration of ideas into images. Migrantsborne-across humansare metaphorical beings in their very essence; and migration, seen as a metaphor, is everywhere around us. We all cross frontiers; in that sense, we are all migrant peoples.

One need not invoke Thomas Mann, Primo Levi, Milan Kundera or anyone else (the list is long) who left home in order to survive and write, to catch the validity of Rushdies assertion. A quick glance at the group of writers gathered herefrom Seferis and Cavafy to Gippius and Nabokovreveals how many migrated, exiled themselves or were exiled. Which again brings up the salient question about whats been lost along the way.

Radical Shadows invites, I hope, more of this sort of cultural investigative work, and an appreciation both of translatorsthose who bear-across work from one language to anotherand everyone else who strives to complete the canons of our important writers.

I owe a debt of gratitude to many people who helped make Radical Shadows possible, above all my co-editor, Peter Constantine. Also, I would like to thank others who brought manuscripts to our attention, as well as those who helped with securing permissions, and gave us leads and suggestions: Andr Aciman, Beth Alvarez (University of Maryland Library, College Park), Jin Auh (Andrew Wylie Agency), Cal Barkside (Arcade), Daisy Blackwell and Georges Borchardt (Borchardt Agency), Andreas Brown, Gerald Clarke, Caroline Donner, Susan Drury (Authors League Fund), Brian Evenson, Jonathan Foer, Robert Giroux, Florence Giry (Editions Gallimard), Lynn Goldberg (Goldberg McDuffie Communications), Alia Habib, Petra Christina Hardt (Suhrkamp Verlag), Glenn Horowitz, James S. Jaffe, Robert Kelly, Chuck Kim (French Publishers Agency), Franz Larese (Erker Verlag), Nancy MacKechnie and Gita Nadas (Vassar College Library, Special Collections), Anna Magni, Tom McGonigle, Bruce McPherson, Alice Methfessel, George Robert Minkoff, Kenneth Northcott, Joyce Carol Oates, Barbara Page, Randy Petilos (University of Chicago Press), Alan Schwartz (Truman Capote Literary Trust), Gary Shapiro, Avi Sharon, Dan Simon (Seven Stories Press), Nikki Smith, Frederick Vanacore, Kathy Varker (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Lawrence Venuti, Tom Whalen, John Wronowski and of course everyone at Bard College for their continued support of this project.

Postscript: Our longtime Senior Editor Pat Sims, highly respected by her colleagues at Conjunctions as well as the hundreds of authors shes worked with, is leaving to pursue other interests. On behalf of all of us whove worked with Pat, I wish her the best in her new career. I would also like to welcome Laura Starrett, who joins Conjunctions with our next issue, Eye to Eye.

Bradford Morrow

October 1998

New York City

Fourteen Stories

Anton Chekhov

Translated from Russian by Peter Constantine

TRANSLATORS NOTE

Dont lick clean, dont polishbe awkward and

bold. Brevity is the sister of talent!

Anton Chekhov to his older brother Alexander, February 1889

CHEKHOV WROTE THESE fourteen prose works during the early 1880s, his most productive and prolific period. He had just arrived in the big city and was energetically studying medicine, supporting his parents and siblings, and exploring the streets, taverns, markets and brothels of Moscow, absorbing the citys color and commotion and working it into quick, vivid prose. By the time he was twenty-six he had already published over four hundred short stories and vignettes in Moscow and St. Petersburg magazines.

Next page