This is for all of Chloes friends who came

through our house over the years, especially

Jessica, Lydia, John, Vanessa and, of course,

Miss D

Every creature has a song

The song of the dogs

And the song of the doves

The song of the fly

The song of the fox

What do they say?

Adin Steinsaltz

From Steve Reichs Three Tales

Tyger, Tyger, burning bright,

In the forest of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

S ylvie recited the poem along with the rest of the class. It was the last lesson of the day. George was sitting next to her trying to kick her legs. Their form teacher, Miss Coates, stood in front of them, her eyes scanning the room for anybody who hadnt yet learned it properly. The first lines of the poem seemed straightforward enough, the tiger with his bright shining eyes prowling through the jungle, but she couldnt get her head round the second half too well. Immortal hand what did that mean? And symmetry? Shed never even heard of the word. But despite it all, it did make a sort of sense, this fabulous beast with its great rippling body and huge padded paws.

She and Dad had been to the zoo the Sunday before last. The zoo was down by the coast, with large pens for the animals that ran down to the marshes. Beyond lay the sea and the abandoned lighthouse that always seemed shrouded in mist. It had been a strange day. All the animals had seemed on edge, running back and forth in their compounds, calling to one another in shrill, agitated voices all except one: the solitary tiger. He lay stretched out on the ground, his great head on the packed earth, as if he was listening to something far away. His cage was set back, a fenced-off no mans land in between him and the path. He was lying near the bars. Sylvie had stood as close as possible, drawn to his immense size, his frightening weight, the strange, unsettling quietness of him.

I wonder what hes thinking, she had said.

A man once wrote, If a tiger could talk, we wouldnt understand a word he said, Dad told her.

Sylvie frowned. I dont get it, she said.

What he meant was that tigers dont see the world as we see it. No animal does. If the tiger could paint you a picture of how the world looked to him, you wouldnt recognize it. How we talk well, thats a way of describing our world: a tall tree, a brown cow, a red sky. So if a tiger could speak, he would not describe what we saw, but what he saw, and it would sound as strange to us as if he was an alien from outer space. Do you understand?

Sylvie had nodded her head, but she didnt really. Yet looking at the tiger that day, she had an inkling of what her father had meant. What lay behind those eyes? What went on in that great head? When he looked at her, what did he see? A thirteen-year-old girl with long fair hair, thin and strong and small for her age? A friend? A foe? A snack in-between meals? As if in answer to her silent questions, the tiger had raised his immense head and stared back, first at her hands, and then straight into her eyes. She could feel his presence boring into her. It was almost as if he was trying to tell her something. Then, without warning, he bared his teeth and, throwing back his head, gave a huge roar, a wild animal sound, fit for a untamed forest, standing proud on the point of a craggy rock, not hemmed in on a patch of arid ground in a corner of Kent. She had stood back, ashamed.

George kicked her legs again. A sharp voice broke in from the front of the class.

Sylvie! Did you hear what I said?

What? Sylvie jumped back to the present, still thinking about that day. She was completely lost. The class murmured. Trouble ahead.

Miss Coates tapped her fingernails on her desk, making a hollow drumming sound, like rain on a tin roof. She was a nice enough form teacher but, like most teachers, hated it when you didnt pay attention.

So enlighten us all please, Sylvie: symmetry. What do you think it means?

Sylvie glanced around. George was looking down at his desk, trying not to be noticed. He was staying over in two days time. Then it was the last day of school and the beginning of the summer holidays.

Well, Sylvie, Miss Coates intoned. All agog, we are, waiting.

There was a ripple of laughter. Miss Coates glanced triumphantly around the room.

Sylvie didnt know what the word meant, but in her mind she saw the tiger in front of her, pacing up and down in his cage, sunlight falling on the length of his massive body, his muscles rippling under his skin with each step he took; his domed head, his slow sweeping tail, his heavy trembling mouth all waiting, watching, every part of him ready to jump into action, to tear the world apart.

Perfect, Miss Coates. Does it mean something like perfect? Like everything about a tiger is just so.

And Miss Coates had to admit that, yes, it did mean something like that: there was something about a tiger that was just so.

The bell rang. School was over for another day.

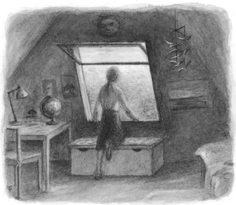

On Mondays and Tuesdays Sylvie stayed behind. Mondays she worked in the library, doing her homework, Tuesdays she learned the flute. But today was Monday, and after an hour and a halfs homework she caught the bus down to the station and the train home. Sylvie and her dad lived on the edge of their small Kentish village, at the end of a row of semi-detached houses, red brick and ivy on the outside, wooden floors and high ceilings inside. It was an ordinary sort of house, a bit messy, in need of a coat of paint though, being at the end, they had a bigger garden than most of their neighbours. However, the one out-of-the-ordinary part of the house was Sylvies bedroom.

Once it had been the attic, dark and uninviting, full of broken furniture and cardboard boxes, but on Sylvies twelfth birthday Dad had converted it into her very own room, as long as the whole house, with a huge window knocked into the roof from where she could look down onto the back garden and the disused railway track that ran along the back of it. The stairs leading up to it were not fixed onto the walls but were attached to the inside of the trapdoor, and were pulled down onto the landing by means of a long rope. Sylvie had hung Mums last photograph, the one with her waving in her green swimsuit, on the wall facing the stairs, so every time she went to bed, it was as if Mum was wishing her goodnight. Most of the time the steps were left down, but when she felt like it, Sylvie could climb up to her bedroom and pull them up like a drawbridge, sealing the bedroom off from the rest of the house. She liked shutting herself away sometimes, having the world and her room all to herself. It made her feel strong, as if nothing could stop her from being who she was, and who she wanted to be.