speech. As a result of this written-language bias (Linell 2005) that has long dominated linguistic research, many structural features that are characteristic of spontaneous spoken language as well as the form and function of many indexical elements that are frequently used in speech are still in need of investigation. This book focuses on one particular kind of such indexical elements, namely final particles.

In the current volume we have brought together sixteen studies on final particles in different languages of the world to take stock of some of the recent advances in the study of these elements and to contribute to broadening and deepening our understanding of their function and syntactic status, their coming-into-existence (often considered an instance of pragmatic role of the final position in a sentence or an utterance.

In this introduction, we will first sketch some general ideas about final particles and the relevance of the study of final particles for linguistic theory

Sylvie Hancil, University of Rouen; Margje Post, University of Bergen; Alexander Haselow, University of Rostock

(Section 2) before providing a typological overview of different types of final particles (Section 3). In Section 4, we will briefly present the different contributions to this volume.

2 Final particles as a research topic

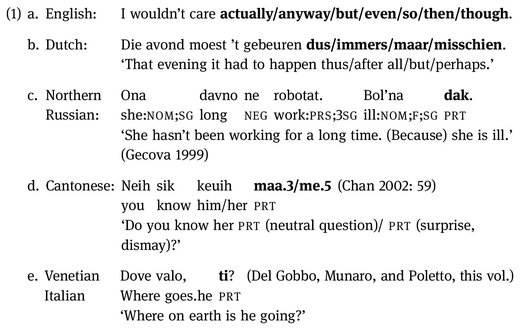

procedural meaning in terms of Blakemore (1987) in that they provide an interpretive cue to the hearer as to how to understand the sentence or utterance they accompany. Some examples are given in (1).

The elements highlighted in bold in (1), which occur predominantly in spoken discourse, are what we and many other linguists analyzing these items call final particles (FPs). More specific terms are sentence-final and utterance-final particles. The term sentence-final particle is widely used for Asian languages and in studies written in a complete sentence and the particles themselves usually have no constituent status. We have chosen to use the neutral term final particles and leave it to the authors to decide which term fits their data best.

Final particles are often classified in a more general way as a sub-class of what has been called, among others, discourse markers (Schiffrin 1987; 2001; Fraser 1999), metapragmatic information (e.g. emotive, epistemic) and information on the rhetorical relation to a prior discourse unit, situating an utterance in a specific communicative context. FPs thus serve an utterance-integrative function in ongoing discourse.

While FPs are quite common and relatively well-documented in East and Southeast Asian languages, the phenomenon has not been investigated in detail for European languages, in which the use of final particles appears to be increasing. At least some FPs have been part of everyday be occupied by an increasingly larger set of elements over the history of English, some of which developed later than others, the youngest type being retrospective contrastive markers (then, though, actually, after all). The use of final particles is thus probably the result of ongoing syntactic changes that are interwoven with changes in discourse organization. This shift, which may well be ongoing in other European languages as well, has not been widely recognized and is therefore worth studying.

While most research on FPs has been done for East Asian languages (e.g. Luke 1990; Okamoto 1995; Sohn 1996; Onodera 2000; Strauss 2005; Wu 2004; Li 2006; Lee 2007; Kita and Ide 2007; Sybesma and Li 2007; Haugh 2008; Yap, Wang, and Lam 2010; Davis 2011; Saigo 2011; Rhee 2012, and the references therein), little of this is known to researchers of European languages. Unifying the studies on FPs allows for a cross-fertilization of Asian and European linguistics and for truly integrative approaches to the study of the syntax of spoken language: hypotheses formulated for the development and the function of FPs in different languages can be tested against each other, and descriptions of the function of FPs in one language often find their proper place if judged against other languages, especially when they are genetically unrelated. Most of the contributions to this volume suggest that the factors underlying the development and the use of FPs are similar in typologically distinct languages since FPs are not necessarily licensed by syntactic rules, but motivated by discourse needs and turn-taking) that hold for all speakers irrespective of the underlying language. On these grounds, a typological perspective seems justified.

The study of FPs has a lot to offer for linguistic description and studies on discourse structure. There are at least six domains in which the study of final particles sheds new light on linguistic theory:

- (i) Theories of categorization.

- (ii) Syntactic Theory: The syntactic status of FPs is far from clear. The role of the final position (or right periphery, or post-field) in the construction of a sentence or a structural unit of any type (an utterance or unit of talk) needs to be rethought in order to encompass FPs.

- (iii)

- (iv) Discourse Analysis and Conversation Analysis: FPs are used to structure jointly produced discourse. They have a cohesive function that needs to be explored and related to the conditions of turn-taking system that regulates interpersonal communication.

- (v) Discourse-Pragmatic Variation: Both the initial and the final position are preferred places for the indication of information that is relevant for the processing of a message. More attention needs to be paid to the question if, and in what way, the initial and the final position differ in their communicative function.

- (vi) diachronic pathways.

generative approaches), others more on theories of grammar and grammaticalization (e.g. Heine, Kaltenbck and Kutevas article), and many of them include data and discussions that are relevant for hypotheses and theories in several domains (e.g. Hancil on final but, Urea Gmez-Moreno on final adverbials in English).

A challenge for linguistic description is how to define the class of final particles in opposition to other elements that may potentially be used in final position (e.g. adverbs or tags), and how to integrate the great collection of items that have been identified as final particles in different typologically and genetically unrelated languages into a single category. The discussions of FPs include various types of linguistic items (e.g. adverb-like or conjunction-like elements, or question particles, see Soare, this vol.; Bailey, this vol.) with various kinds of functions (e.g. connective, expressive, modifying, see f.i. Nikolaeva 1985; 2000; Dedai and Miskovi-Lukovi 2010: 2). A further problem is that FPs are usually described as language-specific items (e.g. sentence-final particles in formal criteria and form-function mappings of the respective language. The difficulty thus lies in mapping a supposedly cross-linguistically relevant category to a number of language-specific categories. Moreover, even the most essential formal criterion for an FP, namely the type of unit to which it is final, has not been defined in a uniform way: some authors use the term clause-final, others speak of sentence-final, utterance-final, turn-final or prosodic-unit-final particles.