Contents

Guide

Discourse Particles

Linguistische Arbeiten

Edited by

Klaus von Heusinger, Gereon Mller,

Ingo Plag, Beatrice Primus,

Elisabeth Stark and Richard Wiese

Volume 564

ISBN 978-3-11-048882-1

e-ISBN [PDF] 978-3-11-049715-1

e-ISBN [EPUB] 978-3-11-049348-1

ISSN 0344-6727

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

www.degruyter.com

Josef Bayer and Volker Struckmeier

The status quo of research on discourse particles in syntax and semantics

Josef Bayer: Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft, Universitt Konstanz, Konstanz, e-mail:

Volker Struckmeier: Institut fr Deutsche Sprache und Literatur I & Englisches Seminar I, Universitt zu Kln, Kln, e-mail:

What are discourse particles (DiPs), also known as modal particles (German Modalpartikeln ) or downtoners (German Abtnungspartikeln )? Morphosyntactically, they are simply non-inflecting parts of speech. In this sense, they pattern with prepositions, complementizers, adverbs, focus particles and various other categories. However, DiPs are noticeably different from most of those elements: They show some similarities with the class of higher adverbs and with the class of focus particles. Their grammar is, nevertheless, quite different, as has often been noted: DiPs depend syntactically on sentence types and/or semantically on the speech act that a sentence type represents. DiPs are, however, extra-propositional themselves, in many ways. To give an example, consider rhetorical questions. In English, the question in (1) can be interpreted as a rhetorical question:

| (1) | Who likes to be criticized? |

The expected answer Nobody! is already suggested by the question itself. The reason for this expectation is probably just world knowledge: Most people simply do not like to be criticized. However, there is no linguistic device in (1) which would enforce this interpretation. As a consequence, the more far-fetched interpretation as an information-seeking question is at least technically still possible. Compare (2):

| (2) | Who wants to go shopping today? |

Here, it is not obvious at all that the question should be interpreted as a rhetorical question. It could be, technically, but such an interpretation seems to be rather far-fetched. Again, the interpretation depends on how we see the world: Since many people like to shop, the rhetorical question interpretation remains in the background.

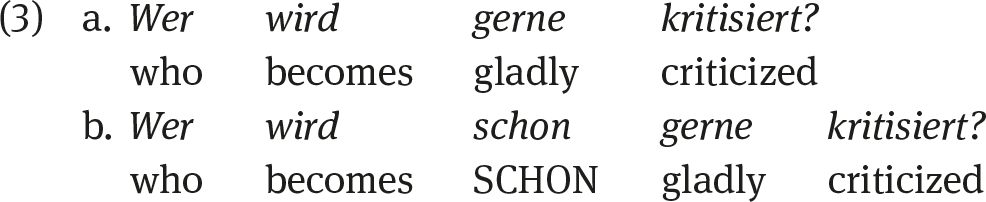

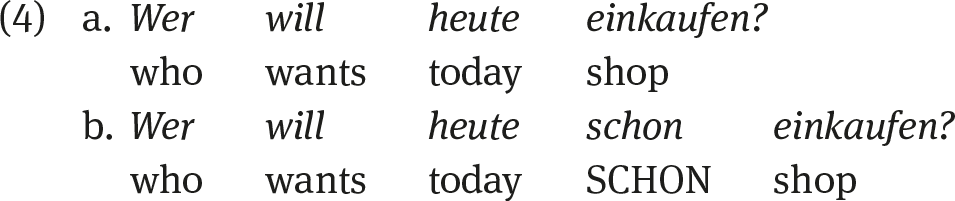

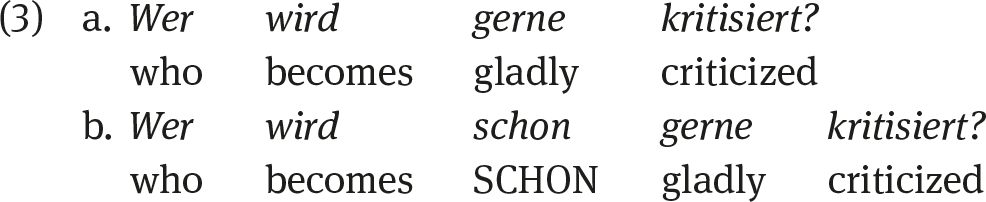

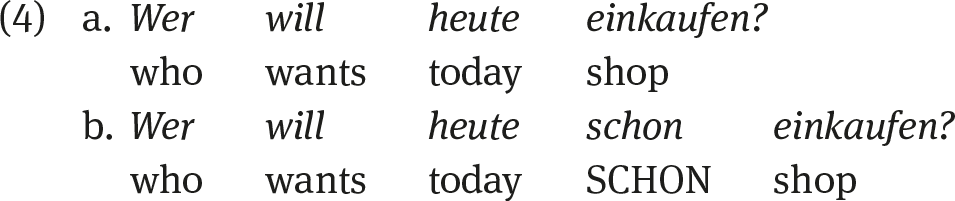

Consider now the following contrasts in German in which the b-examples involve the particle schon (lit. already).

(3a) compares to the English example in (1): World knowledge may easily lead the listener to interpret it as a rhetorical question. (3b), however, only allows for the rhetorical interpretation. The DiPs role becomes even more obvious in (4): A rhetorical interpretation of (4a) appears to be even more far-fetched than for the English example (2). (4a) Who will go shopping today? is quite clearly an information-seeking question. When schon is used, however, as in (4b), it turns unambiguously into a rhetorical question. This demonstrates that the DiP schon is a formal device in the formation of a special interrogative sentence type with a highly specific semantic interpretation. It seems, then, that DiPs do make contributions to the interpretation of sentences, e.g. in relation to sentence types even though their semanto-pragmatic contributions are not always as easily described.

It could be suggested that expressions like on earth or the fuck are English equivalents of certain DiPs in German. Although there are some interesting similarities, the two kinds of expressions do not seem to be completely equivalent. Consider questions as in (5). These can still be considered as information-seeking questions albeit very emotional (or rude) ones:

| (5) | a. Who on earth will go shopping today? |

| b. Who the fuck will go shopping today? |

In the history of linguistics, DiPs have received relatively little attention. In some research traditions, they seem to have remained unidentified or ignored altogether. One reason for this may be that languages differ with respect to the occurrence of DiPs. German is known for its rich inventory of DiPs, whereas English Another reason may be that linguistics is still more in the grip of the grammar of written language than many of its practitioners would like to admit. Since DiPs are dependent on speech acts, they tend to be dominant in spoken language more than in certain written styles. Note, however, that DiPs are clearly attested in certain genres and styles of written language, such as drama, modern prose and quite generally texts that use direct speech. In this sense, they are certainly not to be discarded as some sort of performance phenomenon (such as an overuse of tags, hesitation markers, etc.). A third (and maybe more serious) reason may be that they have so far presented researchers with distinctions that do not always fit neatly into those categories we have come to employ in established frameworks in formal syntax and semantics. From this point of view, DiPs either seem to be too complex to deal with, or researchers believe they can ignore them because they belong to performative aspects of communication rather than to language as a formal system (core grammar). As the present volume attempts to demonstrate, both of these views are probably untenable. More recently, linguists have developed theories, methods and techniques to describe and explain DiPs functions and formal properties in such a way as to integrate them into formal grammatical and compositional semantic frameworks more than ever before.

The study of German DiPs has yielded an impressive body of work in a relatively short time. However in its earliest beginnings, this linguistic endeavor concentrated almost exclusively on the pragmatic or discourse functions of DiPs. Scientifically valid descriptions begin with the (quite insightful) remarks by von der Gabelentz ([1891] 1972). His observations later on became central to authors like Weydt (1969, 1977) who had a strong influence on the pragmatic turn of the 1970s. Strikingly, syntax and formal semantics were almost completely neglected in these early research contributions. While the choice to exclude syntactic and semantic properties was probably, to put it politely, very much in line with the overall aims of this line of research, it also must have seemed difficult, if not altogether impossible to the field in those times to actually get to grips with DiPs from a formal, syntactico-semantic point of view. According to Altmanns (1980) review of Weydt (1977), there was a lack of satisfying semantic analysis which would be able to pick up on speech act theory and Gricean principles of conversation. Simultaneously, there was an increasingly critical evaluation of transformational grammar. One point of criticism was that it was supposed to be inadequate for the description of DiPs.