Bee Wilso n

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFOR D

Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press (??)

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilson, Bee.

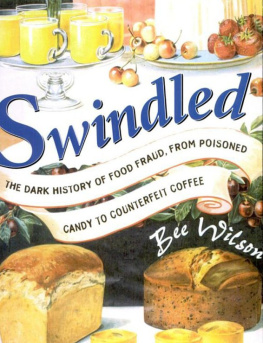

Swindled : the dark history of food fraud, from poisoned candy to counterfeit coffee / Bee Wilson.

p. cm. Previously published: London : John Murray, 2008. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-13820-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Food contaminationHistory.

2. Food industry and tradeHistory . I. Title. TX531.W688 2008 363.1926dc22 2008009688

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For David, Tom, and Natash a

Do we recognize the dishonesty of our tradesmen with their advertisements, their pretended credit, their adulterations and false cheapness?... It is not of swindlers and liars that we have need to lie in fear, but of the fact that swindling and lying are gradually becoming not abhorrent to our minds.

Anthony Trollope, The New Zealander, 1856

Content s

| Preface | xi |

|

| German Ham and English Pickles | 1 |

| 2 |

| A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread | 46 |

| 3 |

| Government Mustard | 94 |

| 4 |

| Pink Margarine and Pure Ketchup | 152 |

| 5 |

| Mock Goslings and Pear-nanas | 213 |

| 6 |

| Basmati Rice and Baby Milk | 272 |

| Epilogue: Adulteration in the Twenty-first Century | |

| Notes | |

| Bibliography | |

| Acknowledgments | |

| Picture Credits | |

| Index | |

Preface

None of us likes being swindled, particularly when all we were try ing to do was buy something nice to eat. The feelingof mortification mingled with furyis wholly disagreeable, but it is also very familiar. Being cheated over food is one of the universal human experiences. We have all been overcharged for a quart of milk; or shortchanged on a pound of strawberries; or sold an additive-laden loaf of bread that pretended to be natural; or served a home-made soup in a diner that came from a can; or eaten bacon that turned to water in the pan. Sometimes we gaze, bitterly, at the shoddy or overpriced food on our plate and wonder if there were older, simpler times, when honesty reigned and both food and its sellers had real integrity. Having researched the question for this book, I can only say that these idylls, if they existed at all, were very infrequent and short-lived. Food fraud has a long history, and it is mixed up with all the other forcesscientific, economic, politicalthat went together, for better and worse, to create the world we live in. In many ways, the history of food fraud is the history of the modern world.

Food has always had the power to kill as well as cure. All things are poisons; nothing is without poison; only the dose permits something not to be poisonous, said the alchemist Paracelsus in the sixteenth century. Perhaps; but some foods are much more poisonous than others. If you drink enough carrot juice, you can make yourself ill; in 1974, a health nut called Basil Brown drank ten gallons of carrot juice in conjunction with ten thousand times the recommended dose of vitamin A; he died as a result. But the really dangerous poisons are those whose dose is a normal portion. There are plenty of these in this story: childrens candies dyed with copper and mercury; diseased meats dosed with chemicals to look fresh; wine sweetened with lead.

Not all poisons in food are swindles: some are entirely accidental. But what makes adulteration (deliberately tampering with food) worse than contamination is the element of intent. Behind every poisonous swindle is another human being (oft en, a whole team of them), who was prepared to damage your health if it meant a quick buck for them.

Adulteration is an ungainly word, and it can seem hard to pin down at times. What counts as tampering? Am I adulterating a cake recipe when I add some extra vanilla to it? someone asked me recently. No, you are cooking, I replied. It is true, though, that ideas of adulteration have changed radically over time. In the 1850s, salt was listed as an adulterant of butter (partly because it was used to disguise butter that was going rancid). Now, salty butter is sold to those who enjoy it without any intention to deceive. By the same token, hops are now considered an essential ingredient in beer. But when first introduced, hops were viewed with deep suspicion as a rogue element in a true Englishmans ale. It took a century for hops to cease being an adulterant and become an innocent ingredient. The opposite pattern prevails now, as many ingredients once seen as harmlesssaccharine, food colourings, trans fats (the hydrogenated fats that, until recently, were a routine ingredient in biscuits, cakes, and breakfast cereals)come to be redefined as adulterants.

Yet for all these fluctuations, adulteration can be reduced to two very simple principles: poisoning and cheating. In the old common law, it was an offence to sell food that was not wholesome for mans body, assuming that the seller knew what they were doing. Common law also made it an offence to sell food as something other than what it actually waswhether because it was of short weight, or padded or diluted, or because a cheap food had been substituted for an expensive one. Although the laws against adulteration have varied widely at different times and places, they have always had these two basic ideas at their core: Thou shalt not poison and Thou shalt not cheat.

These are not just personal matters, between a buyer and a seller; they affect an entire society. Adulteration is one of the longest-standing concerns of law and government, not only for its own sake but because it impinges on so many other matters of grave importance. It is a question of public health, but also of economics. From the earliest times, governments have seen swindling as a threat to economic order and to their own authority. In addition to the more immediate victims of the crime, food cheats damage the exchequer, since they avoid paying the full taxes they would have been liable to pay on the real food or drink. Adulteration is a threat to civilized politics, too. Governments have sought to police food fraud because to permit it to carry on unpunished is a sign of anarchy. A society in which swindling is rife is one in which fundamental trust between citizens has broken down. It is therefore a vital concern of politics to stop it.

Even so, for the past two hundred years many governments have allowed swindlers to get away with outrageous crimes. This is a story of turpitude and greed, of the vile indifference with which some human beings will treat the health of others if it means making money. But it is also a story of a failure of politics; of the deep reluctance of postindustrial governments to interfere with the markets in food and drinksomething earlier governments were happy to doeven when those markets have become dishonest and dangerous. The heroes of the story are not for the most part politicians, but scientistsdetectives of the kitchenwho have dared to use every tool at their disposal to expose the manifold ways in which food is tampered with, padded, dyed, faked, diluted, substituted, poisoned, mislabelled, misnamed, and otherwise falsified.