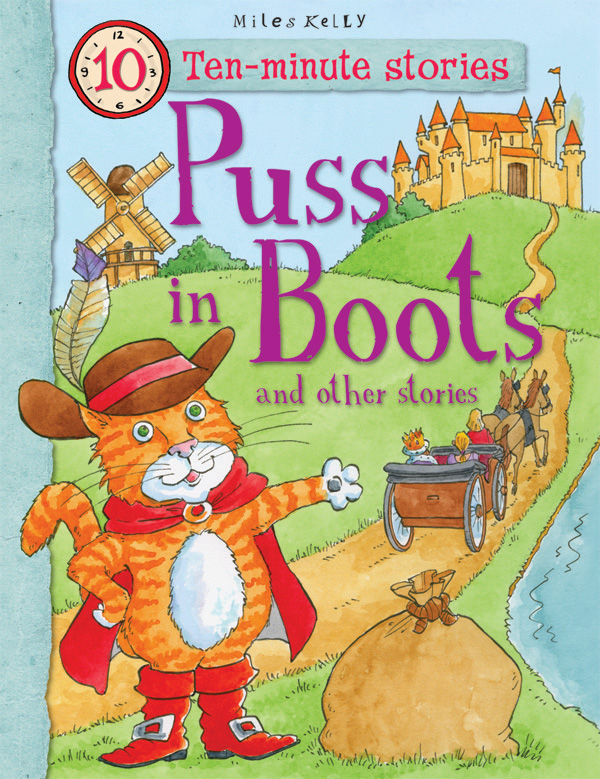

First published in 2011 by Miles Kelly Publishing Ltd

Hardings Barn, Bardfield End Green, Thaxted, Essex, CM6 3PX, UK

Copyright Miles Kelly Publishing Ltd 2011

Publishing Director Belinda Gallagher

Creative Director Jo Cowan

Editor Amanda Askew

Senior Designer Joe Jones

Production Manager Elizabeth Collins

Reprographics Anthony Cambray, Stephan Davis, Lorraine King, Jennifer Hunt

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Artworks are from the Miles Kelly Artwork Bank

Cover artwork by Mike Phillips (Beehive Illustration)

Every effort has been made to acknowledge the source and copyright holder of each picture.

Miles Kelly Publishing apologises for any unintentional errors or omissions.

www.mileskelly.net

info@mileskelly.net

www.factsforprojects.com

The Spider and the Toad

From Wood Magic by Richard Jeffries

O NE MORNING AS LITTLE SIR BEVIS (such was his pet name) was digging in the farmhouse garden, he saw a daisy, and throwing aside his spade, he sat down on the grass to pick the flower to pieces.

A flutter of wings sounded among the blossom on an apple tree close by, and instantly Bevis sat up, knowing it must be a goldfinch thinking of building a nest in the branches. If the trunk of the tree had not been so big, he would have tried to climb it at once, but he knew he could not do it, nor could he see the bird for the leaves and bloom. A puff of wind came and showered the petals down upon him; they fell like snowflakes on his face and dotted the grass.

Buzz! A great humblebee, with a band of gold across his back, flew up, and hovered near, wavering to and fro in the air as he stayed to look at a flower.

Buzz! Bevis listened, and knew very well what he was saying. It was, This is a sweet little garden, my darling; a very pleasant garden; all grass and daisies, and apple trees, and narrow patches with flowers and fruit trees one side, and a wall and currant bushes another side, and a low box-hedge and a haha, where you can see the high mowing grass quite underneath you; and a round summerhouse in the corner, painted as blue inside as a hedge-sparrows egg is outside; and then another haha with iron railings, which you are always climbing up, Bevis, on the fourth side, with stone steps leading down to a meadow, where the cows are feeding, and where they have left all the buttercups standing as tall as your waist, sir. The gate in the iron railings is not fastened, and besides, there is a gap in the box-hedge, and it is easy to drop down the haha wall, but that is mowing grass there. You know very well you could not come to any harm in the meadow; they said you were not to go outside the garden, but thats all nonsense, and very stupid. I am going outside the garden, Bevis. Good morning, dear. Buzz! And the great humblebee flew slowly between the iron railings, out among the buttercups, and away up the field.

Bevis went to the railings, and stood on the lowest bar; then he opened the gate a little way, but it squeaked so loud upon its rusty hinges that he let it shut again. He walked round the garden along beside the box-hedge to the patch by the lilac trees; they were single lilacs, which are much more beautiful than the double, and all bowed down with a mass of bloom. Some rhubarb grew there, and to bring it up the faster, they had put a round wooden box on it, hollowed out from the sawn butt of an elm.

One of these round wooden boxes had been split and spoilt, and half of it was left lying on the ground. Under this shelter a toad had his house. Bevis peered in at him, and touched him with a twig to make him move an inch or two, for he was so lazy, and sat there all day long, except when it rained. Sometimes the Toad told him a story, but not very often, for he was a silent old philosopher, and not very fond of anybody. He had a nephew, quite a lively young fellow, in the cucumber frame on the other side of the lilac bushes, at whom Bevis also peered nearly every day after they had lifted the frame and propped it up with wedges.

The gooseberries were no bigger than beads, but he tasted two, and then a thrush began to sing on an ash tree in the hedge of the meadow. Bevis! Bevis! said the thrush, and he turned round to listen: Have you forgotten the meadow, and the buttercups, and the sorrel? You know the sorrel, dont you, that tastes so pleasant if you nibble the leaf? And I have a nest in the bushes, not very far up the hedge, and you may take just one egg; there are only two yet. But dont tell any more boys about it, or we shall not have one left. That is a very sweet garden, but it is small. I like all these fields to fly about in, and the swallows fly ever so much farther than I can; so far away and so high, that I cannot tell you how they find their way home to the chimney. But they will tell you, if you ask them. Good morning! I am going over the brook.

Bevis went to the iron railings and got up two bars, and looked over; but he could not yet make up his mind, so he went inside the summerhouse, which had one small round window. All the lower part of the blue walls was scribbled and marked with pencil, where he had written and drawn, and put down his ideas and notes. The lines were somewhat intermingled, and crossed each other, and some stretched out long distances, and came back in sharp angles. But Bevis knew very well what he meant when he wrote it all. Taking a stump of cedar pencil from his pocket, he added a few scrawls to the inscriptions, and then stood on the seat to look out of the round window, which was darkened by an old cobweb.

Once upon a time there was a very cunning spider, a very cunning spider indeed. The old Toad by the rhubarb told Bevis there had not been such a cunning spider for many summers; he knew almost as much about flies as the old Toad, and caught such a great number that the Toad began to think there would be none left for him. Now the Toad was extremely fond of flies, and he watched the Spider with envy, and grew more angry about it every day.

As he sat blinking and winking by the rhubarb in his house all day long, the Toad never left off thinking, thinking, thinking about the Spider. And as he kept thinking, thinking, thinking, so he told Bevis, he recollected that he knew a great deal about a good many other things besides flies. So one day, after several weeks of thinking, he crawled out of his house in the sunshine, which he did not like at all, and went across the grass to the iron railings, where the Spider had then got his web. The Spider saw him coming, and being very proud of his cleverness, began to taunt and tease him.

Next page