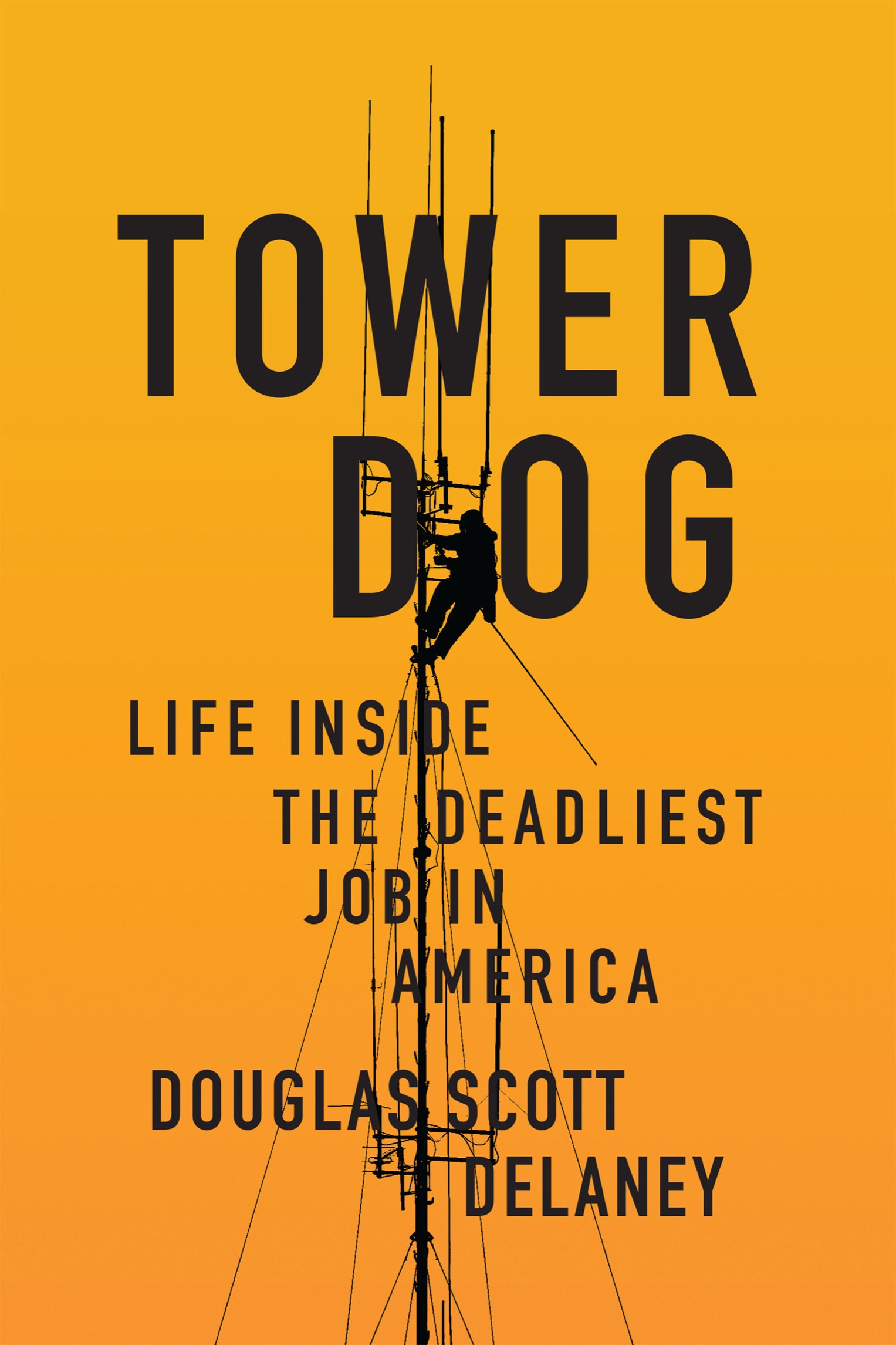

Copyright 2017 Douglas Scott Delaney

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover design by Faceout Studio

Interior design by Tabitha Lahr

eISBN 978-1-59376-676-4

SOFT SKULL PRESS

An Imprint of Counterpoint

560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.softskull.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ali, who made anything possible.

For Brian, so some day he might understand.

Author's Note

I began typing this story on January 4, 2013. Since then, thirty-five of my subjects have died, averaging one every 40 days.

And not from natural causes.

This story is true. Some names have been changed to protect the moronically guilty, the chronically modest, and the otherwise disengaged. Some locations have been changed as well.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

THE GREEKS HAD A WORD FOR IT

Kansas used to be an ocean. Stick a shovel deep enough in any part of the state and you are likely to unearth some plankton-sucking platywhoozitz big as Wall Street. On the weekends you can find geology and paleontology students lined up along the jagged cuts in the blue highways digging out the fossilized florand fauna from eighty-five million years ago. Rudists, crinoids, squid, ammonites, sharks, bony fish, turtles, plesiosaurs, pteranodons, andbe still, my beating heartgiant clams. When the ocean receded it left behind a topography no one ever associates with Kansas, for

Kansas is many countries. It is Ozark Country, high desert, expansive prairie, Monument Valley, Yorkshire Dales, wildflower heaven, and, in places, even deeply forested. People think Kansas is flat and unpleasant, and that is fine with Kansans because as Doc Wimmer, my biology teacher at Southwestern College, would say, If Kansas still had an ocean, everyone would live here. Part of that residual topography is the continents largest remaining tract of tallgrass prairie, four million acres of it, that lies in the eastern third of the state. These are the Flint Hills.

The Flint Hills stretch almost border to border from Marshall County up by Nebraska to Cowley County in the south before extending down into Oklahoma. A portion of I-35 slices through the heart and most scenic section of the Flint Hills for 117 miles. The first time I ever drove through the Flint Hills, I had to pull over and stop to admire the austere beauty of it all. My typing cannot do the place justice. William Least Heat-Moon devoted 624 pages to the hills in his New York Times bestseller PrairyErth , so I am not even going to try to match words with that guy. But for those with an affinity toward the unforeseen density of empty places, the Flint Hills are the place to be, even though if you took your kids there on vacation they would seek to have you committed or at least sanctioned by the Ministry of Fun.

Each April during the burning season, the fires can be seen from space, and if you are fortunate enough to view this from ground level, you would get a new appreciation of hell on earth. This burning, which for tens of thousands of years was a natural occurrence, has only changed in its method of ignition. It used to be lightning (and still can be), but in our intrinsic human quest to control everything, the burning is now carefully orchestrated between the farmers and ranchers and several bureaus of land management, the fires started with various homemade and store-bought contraptions. But the end result is the same. Dazzling.

It took a while for the early homesteaders of the mid-1800s to appreciate this. Shortly after they slapped together sod houses along one of the few flowing creeks and began to turn the land, representatives of the Kiowa, Osage, or Kansa dropped by to tell them, You might want to rethink this one . The settlers did not take this in the spirit of high-plains fellowship it was meant, but (the white mans burden lying heavily on their shoulders) instead as being warned off the land by a bunch of Christless savages, a matter they would have to attend to as soon as the crops were in and they could scrape up enough wood to build a church. What the Kiowa, Osage, or Kansand their progenitors had known for about twelve thousand years was that the creeks would dry up for months come the summer, the land was not very good for raising crops, and when the spring conflagration came, the settlers would be hauling ass back to the Missouri River landings up in St. Jo faster than they could say land grant. After they figured out that the fires were not being caused by hostiles, the settlers settled and each year tried to raise the same unraisable crops and went nearly insane with thirst and dug holes in the earth to escape the yearly inferno. Any wood for churches was soon resigned to keeping the hearths crackling throughout the heartless plains winters. But they stayed anyway.

The Greeks had a word for that. They called it akrasia . Loosely translated it means the tendency to gravitate toward danger when there are safer alternatives available . Socrates (in Platos Protagoras ) asks precisely how this is possible because if one judges action A to be the best course of action, why would one do anything other than A? I asked this question of myself on my very first tower just north of El Dorado, Kansas, in the winter of 1997. I looked up at the 240-foot guyed-wire tower and thought, Why would one?

Second thoughts? Angelo Kilfoyle said.

Angelo Kilfoyle, a.k.a. Power, due to what we yelled every time we needed some real heft behind a chore, had the teeniest I know something you dont know smile on his face when he said that.

No shame in it, he said. Just the dog.

At the time I lived about ninety minutes from that spot, so getting the dog did not concern me at all. Getting up that tower did. I did not want to do it. I had been trained days earlier at my house, hanging from the pecan trees in my belt as Angie and Hangman familiarized me with the equipment. I had no problem with that; they told me I was a natural. They held back the fact that twenty-foot pecan trees shared little in common with 240-foot guyed-wire towers. They knew, though they admired my self-deceiving confidence, that I would have to figure that out for myself. I had met Angie in a bar in Astoria, Queens, shooting pool, and for reasons we still cannot agree upon he threatened to kick my ass. Not in eight-ball but to kick your igrant Yankee ass right here and now . He was fifteen. I was twenty-seven. Power was what my dad would call a fireplug. Five-foot-nine-inches tall and stout from neck to ankles, biceps like hams and thighs like bigger hams. He had straight brown hair down to his ass that he put in a ponytail and, when it reached his butt-crack, he would cut it off and donate it for wigs for children undergoing chemotherapy. And he had a crystalline outlook on the world as a whole. Life was two things: fucked-up or hilarious.

Next page