Table of Contents

Guide

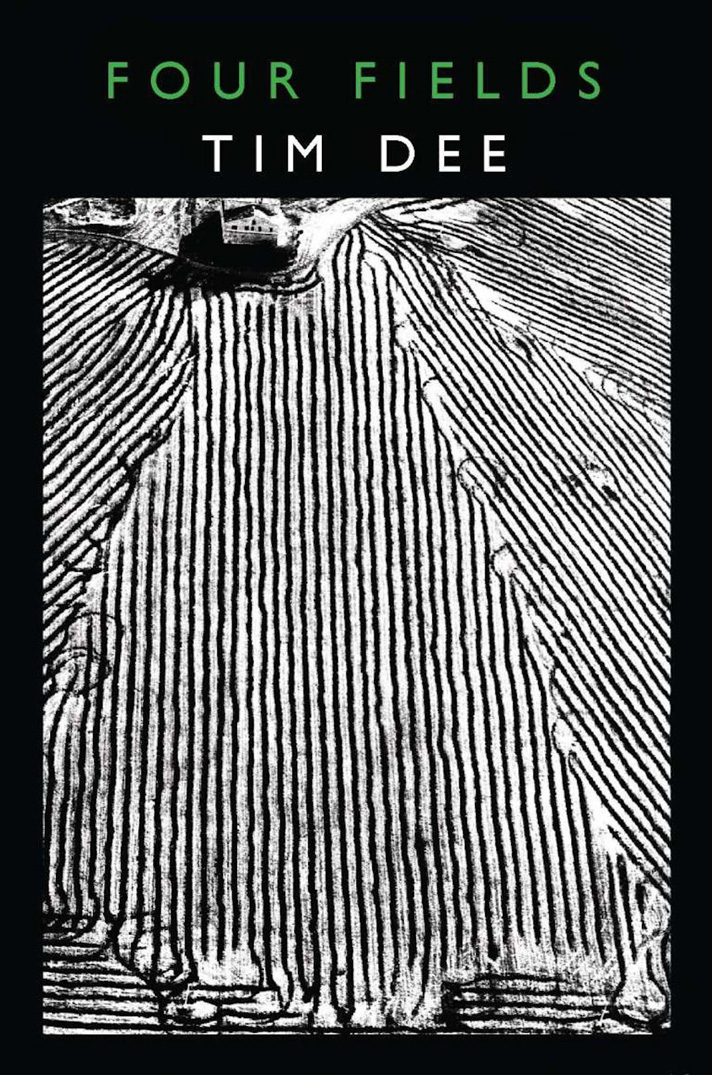

FOUR FIELDS

ALSO BY TIM DEE

The Running Sky: A Birdwatching Life

The Poetry of Birds (co-editor with Simon Armitage)

Copyright 2015 Tim Dee

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Is Available

ISBN 978-1-61902-507-3

Cover design by Julia Connoly

Interior Design by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Counterpoint Press

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

husbandry

for Claire

CONTENTS

A man keeps and feeds a lion. The lion owns a man.

Diogenes

I was driving home in the dark. The stop-start charms of the A14. Lorries, boxy with containers heaving into the night, metal bergs not long off the sea struggling over the land, Stonehenge and Easter Island heads to be delivered to the interior. Body shunts and heart attacks on every incline. The Midlands up in front. Dusk had taken the fields next to the hurrying road out of sight. The lit trench was all. I was thinking of nothing, as you must to survive, when stems of grass suddenly glanced in my beams and crowded at my windscreen, their straight thin bars of strobing light tinkling against the glass. Somewhere in front of me a hay lorry was travelling and throwing behind it this green storm. The traffic slowed. As I braked, the hectic sprinkle fell away and I could see in my headlights and then feel beneath my tyres that the whole of the roads surface was covered in the thinnest spread of hay. A cigar butt or two of the stuff must have bounced from the back of the lorry and split on the road. We were all driving on grass. It brought a smile to my face. I might have strayed into some nativity scene of straw carried into a church and spread across a stone floor to make a point. I might have drifted into the story of the Princess and the Pea. The road had been transported or turned over into a kind of field and the grass was announcing itself in our ungreen and ungrowing world. My car and all the cars and lorries around me inched forward over the strange luxury beneath our tyres and, though the hay blades were thin and crushed thinner, I could still feel the new field under me with its tiny ridges and furrows briefly repossessing the road.

Throughout my life much of my happiness has come from being outside. That brief smile on the A14 was declaring it. I became a serious birdwatcher at the age of seven in 1968. Ive grown less serious with time but, ever since my childhood, going out into the field has been part and parcel of what I do. The field might mean the fields of a farm but it can also mean anywhere that birds live and especially places where you deliberately look for them. Mostly this has been away from towns and cities, but not always: a back garden would do on a good day, or a park. My wanting to see birds simplified the world: if you didnt go out, you didnt see anything; if you did go out, regardless of what you saw, you seemed to have been somewhere and to have done something. Thoreau used the same phrase having spent a day kneeling to the earth to collect fallen sweet chestnuts in October 1857. Any day out for me, any day in the field, was better than a day indoors I think that is what Thoreau meant too. Being outside was never a waste of time: even a day in July in a wood in the middle of England at the years green midnight, when no birds sing; even an expedition in February with a grumpy girlfriend to an urban sewage farm; even a day with only a pitiful species list or wet feet to show for your efforts. Without any fieldwork of this kind, life inside stalled. Long before I read it, I knew the damp grey constriction in my chest and between my eyes of the first page of Jane Eyre: There was no possibility of taking a walk that day.

Indoors, looked at from the field, seemed at best to be talk about life instead of life itself. Rather than living under the sun it fizzed if it fizzed at all parasitically or secondarily, with batteries, on printed pages, and in flickering images. I realised this around 1968 in my seven-year-old way. At the same time, however, I learned that I needed the indoor world to make the outdoors be something more than simply everything I wasnt. I saw it was true that indoor talk helped the outdoor world come alive and could of itself be living and lovely, too. Words about birds made birds live as more than words. Jane Eyre, held inside by bad weather, takes Thomas Bewicks History of British Birds to the window and reads looking out into the wind and rain.

A yellowhammer on a flaming gorse a mile from my childhood home, my first ring ouzels on spring migration on the grassed bank of a slurry pit these birds, once found and named (real, flighty, not interested), started something off like a shock into living. The world leaned on me, as it were, and the green gears of outside became part of the machinery of my mind, and a language of my whole life, as Ted Hughes described animals in his. Ever since, being in the field, following the fields seasons and its birds, and, at the same time, moving words from indoors out, and outdoors in, has more or less dominated my years.

Without fields no us. Without us no fields. So it has come to seem to me. This green plot shall be our stage, says Peter Quince in A Midsummer Nights Dream. Fields were there at our beginning and they are growing still. Earth half-rhymes with life and half-rhymes with death. Every day, countless incarnations of our oldest history are played out in a field down any road from wherever we are. Yet these acres of shaped growing earth, telling our shared story over and over, are so ordinary, ubiquitous and banal that we have mostly stopped noticing them as anything other than substrate or backdrop, the green crayon-line across the bottom of every childs drawing. It is in the nature of all commonplaces that they are overlooked, in both senses of the word: fields are everywhere but we dont see them for they are too familiar and homely; being the stage and not the show, they are trodden underfoot, and no one seeks them out, no one gives a sod. For Walt Whitman, prairie-dreamer of the great lawn of men, grass fitted us and suited; it was a uniform hieroglyphic. It grew and stood for us and, because it goes where we are, we tread where it grows. Yet because it meant everything it could easily mean nothing.

Might it be possible to look again and to see the grass and the fields afresh? Our making of fields, first of all from that grass, has tied us to nature more than any other human activity. The relationship is rooted yet simple, ancient yet living. Fields offer the most articulate description and vivid enactment of our life here on earth, of how we live both within the grain of the world and against it. We break ground to lay foundations, sow seeds and begin life; we break ground to harvest life, bury our dead and end things. Every field is at once totally functional and the expression of an enormous idea. Fields live as proverbs as well as fodder and we reap what we sow.

The fields! urged John Ruskin, early conjuror of cultural landscapes, follow but forth for a little time the thoughts of all that we ought to recognize in those words. What follows here is an attempt to say some more about the fields in my life; to understand why these four fields mean as much to me as they do and how they have given me the sentimental education, the hearts journey, that they have; to explore what they have meant to others; to discover the common ground they make, the