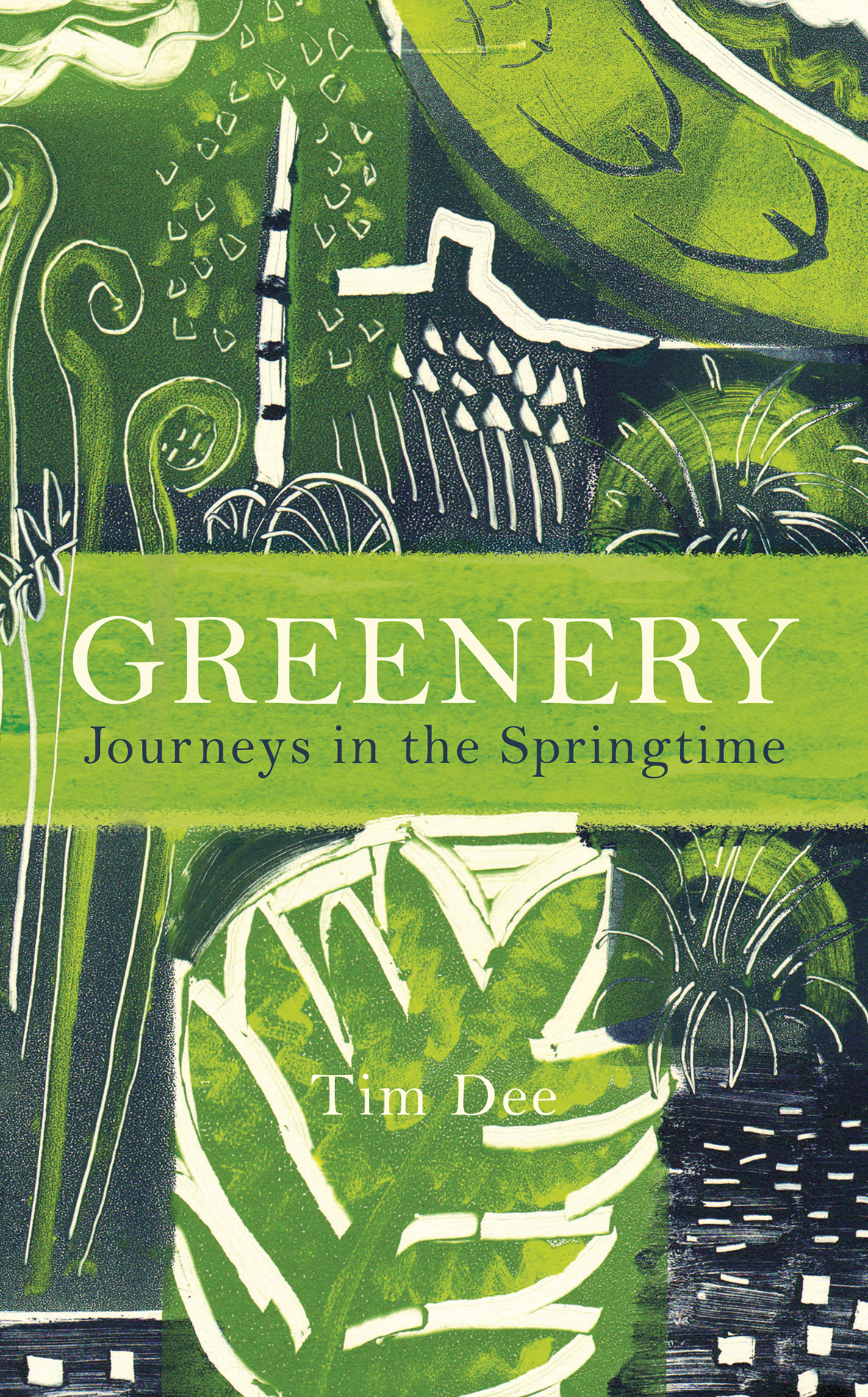

Tim Dee

Greenery

Journeys in Springtime

Contents

About the Author

Tim Dee has been a birdwatcher all his life. His first book, The Running Sky (2009), described his first five birdwatching decades. In the same year he collaborated with the poet Simon Armitage on the anthology The Poetry of Birds. Since then he has written and edited several critically acclaimed books: Four Fields (2013), a study of modern pastoral, which was shortlisted for the 2014 Ondaatje Prize; Ground Work (as editor, 2017), a collection of new commissioned writing on place by contemporary writers; and most recently, Landfill (2018), a modern naturejunk monograph on gulls and rubbish. He left the BBC in 2018 having worked as a radio producer for nearly thirty years. He lives in three places: in a flat in inner-city Bristol, in a cottage on the edge of the Cambridgeshire Fens, and in the last-but-one house from the south western tip of Africa, at the Cape of Good Hope.

A LSO BY T IM D EE

The Running Sky: A Birdwatching Life

The Poetry of Birds (co-editor with Simon Armitage)

Four Fields

Ground Work (editor)

Landfill

For my children

Dominic, 13 October 1993

Lucian, 4 August 1995

Adam, 14 August 2019

offspring

And now in age I bud again

George Herbert

17 March 1780

Brought away Mrs Snookes old tortoise, Timothy, which she valued much, & had treated kindly for nearly 40 years. When dug out of its hibernaculum, it resented the insult by hissing.

20 March 1780

We took the tortoise out of its box, & buried it in the garden: but the weather being warm it heaved up the mould, & walked twice down to the bottom of the long walk to survey the premises.

Gilbert White

The Way Up

Cape of Good Hope

34S

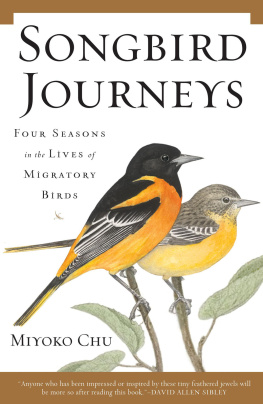

21 December. Midsummer. On the kelpy beach at Olifantsbos there was an ostrich with its head in the sand. I thought it was eating flies. The beach is a few kilometres south of my sometime home at Scarborough, on the western edge of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa. It was a male ostrich, with athletic pinkish legs, a long muscular neck and a heavy bustle of black and white plumes. It could have been Queen Victoria getting ready for a swim. Flying above the unlikely strandloper were three fast-moving small birds, doing battle with the hot buffet of air salted by the Atlantic and gritted by the beach. Heading south, they followed the shore towards the Cape of Good Hope. They were swallows: the gash of dried-blood at their throats told me that, and the blue, metal-shiny crick crack of their sharp wings and deep-cut tails. And they flew, as always, ever so lively.

Cities on the sea, Albert Camus wrote in Summer in Algiers, open out into the sky like a mouth or a wound. The same evening, sitting on the stoep of the house I share with Claire, my South African wife (my only wife she happens to be South African), we looked out west over the Atlantic from our Cape Town suburb into the sloping midsummer sun. There were more swallows and, in identifying them, I saw not only a bird I knew but also how hard it is to see into the heart of anything for sure. A loose flock was moving south between our house and the ocean half a dozen barn swallows (the preferred name today for what I have always called simply swallows) and the same number of greater striped swallows. I knew the barn swallows had left winter behind them in Europe. I knew the greater striped swallows were intra-African migrants that breed (between September and March) across South Africa and then winter further north in Angola, Congo and Tanzania. I was doing my best as a translocated bird-man, living in a world turned upside down, trying to read it right, but, as I looked, I couldnt help but declare my origins and show my head to be, with the ostrich, somewhere in the sand.

The barn swallows flicked low down at the edge of the land between the weedy surf and the white strand. They looked they always do as if they were seeking something. Each knock and slide in their flight appeared an adjustment a correction made with every wing-beat to the delicate blue-black needle of themselves. There wasnt much land left in the direction they flew perhaps ten kilometres of beach and rocky peninsula. And I told them there was nothing where they were going but shipwrecks, whale bones, cold sea and, after that, colder ice, with nothing, absolutely nothing, for them to look forward to, and that theyd do better, on this solstitial evening, to turn and head for home.

I said home. I had lost my foothold on the map. The winter solstice in South Africa is in June. The swallows were where they should be in December, as at home as they could be. But at that moment I couldnt see them as anything but away. Away from a home (in Britain as it happens where some of the swallows that winter in the Cape go to breed) that was mine too, and which, even as I sat next to my wife outside our house, the sight of the birds made me miss.

These Cape swallows in my midwinter (Id left Britain just two days before), in Claires midsummer (which has been written into her for ever hot Christmases), in whatever the time is for the birds there (the non-breeding time, the moulting time, the open-territory time) they tugged at what I have known for all my life, or thought I have known, of birds and how they work in the world. I heard myself say home and laughed aloud to be so found out.

Sometime before 1965, the poet Elizabeth Bishop watched a sandpiper somewhere along the Atlantic seaboard that she knew between Nova Scotia and Brazil. She wrote a poem about the bird. It is very well seen. I suspect the bird is a sanderling, although it is hard to identify as a particular species of peep (which is what American birdwatchers call small shoreline waders). The poem begins on the seas edge and at its breaking waves:

The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

and that every so often the world is bound to shake.

Bishop said that she saw something of herself in the migrant wader working at the wet seam of the shore. All my life, she wrote, of the poem, I have lived and behaved very much like that sandpiper just running along the edges of different countries looking for something.

I have thought the same of myself, but often what I have been looking for, and trying to steer by, has not been a non-specific something, but rather sandpipers themselves, or swallows. For as long as I have been a birdwatcher, birds on the move have given me bearings. If I know how life goes, it is, as much as anything, because of sandpipers and swallows. Thanks to them, Ive heard the roaring of the world too, and I find I know a little of its shakes.

Though the birds I saw were heading south, soon enough all the barn swallows in the Cape will fly north and, eventually, out of Africa and into Europe. They journey in their own time, flying all day, a metre or so above the ground, feeding on flies as they go. Their own time turns out to be the right time and they arrive where they need to be on time. Mostly this is the case. Early in the new year the first barn swallows cross the Mediterranean into southern Europe. This might be one definition of the beginning of spring.

Next page