Praise for Honeymoon in Purdah

With an open heart, a sharp eye and a fine-tuned ear, Alison Wearing lets the Iranians she encounters create with their own words a kind of collective self-portraita vocal mosaic of a misunderstood people. Honeymoon in Purdah is lively, moving andlike most books that offer genuine insightsextremely funny.

Steven Heighton

An engaging and lyrical work. Its sharp yet sympathetic eye for detail allows the everyday citizens whom the author encounters and observes to emerge from behind the stereotype and reveal what Wearing herself calls the poetry of their lives. Calgary Herald

Bright and searingly observant, [Wearing] paints indelible moments from her honeymoon with Iran. The cumulative effect is like reading Alice in Wonderland.The Toronto Star

Alison Wearing has assembled a series of rich and funny anecdotes about Iran, a nation few Westerners get beneath the surface of, let alone visit. Macleans

Honeymoon in Purdah is the perfect travel memoir: Observant, wise and very funny. Chock-full of descriptive narrative, it is so evocative I ended up craving pistachios and could almost feel that chaador. The Calgary Sun

Alison Wearing is a great guide for the armchair tourist. Best of all, she helps Western readers see, hear and smell this Middle Eastern nation that is a crossroads between ancient and ultra-modern cultures. Entertaining and informative. The Toronto Sun

Honeymoon in Purdah is a luminous account of travel into territory unknown to most Westerners, a warm and affectionately descriptive trip that was meant to be shared. The Record (KitchenerWaterloo)

Wise, compassionate, amused and amusing, Alison Wearing is the ideal travelling companion, and this is the most vital account of contemporary Iranin all its tragic-comic dimensionsI have read.

Paul William Roberts

for my mother

AUTHORS NOTE

This is a sketchbook, a collection of my impressions of Iran and its people. For the most part, I have painted situations as they occurred, presented voices as precisely as possible. At times, I have made collages of stories and faces, as often to protect the identities of people as to lend artistry to a scene. As is the case with many portraits, their truth is not in their detail, but their spirit.

CONTENTS

T HIS IS THE ROOM that leads to Iran. It is oblong. A door at each end. Bare, but for two portraits, one above each doorway. General Kemal Atatrk watches over the edge of his land from the western door. The Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini from the east. I walk to what feels like the middle of the room and stand like a flamingo, balancing between countries.

I fall back onto both feet when a group of women blows through Atatrks door. They are ancient and wizened, tiny, all of them, and wrapped in white veils. They flutter around each other, then squat on the floor holding fistfuls of fabric under their chins. Their teeth act as an extra set of fingers, gripping and tugging their covering constantly, obsessively, as though they could work at it all day and never get it quite right. They are so skittish that the slightest thinga door opening, someone walking too close to them, a question directed at themsends them scurrying off in all directions. Startled chickens. They shriek and scatter, veils flapping, feet shuffling; then, gradually, they regroup, their pitch drops, the movement settles, and they return to quiet chatter and the business of covering themselves.

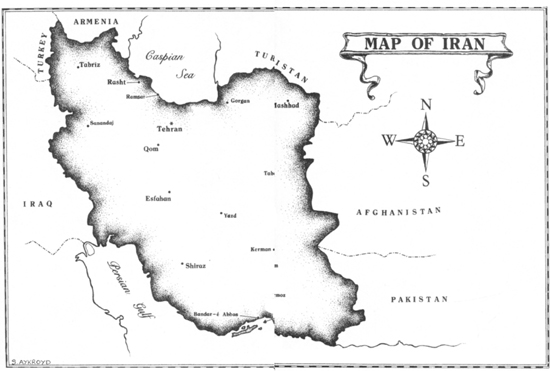

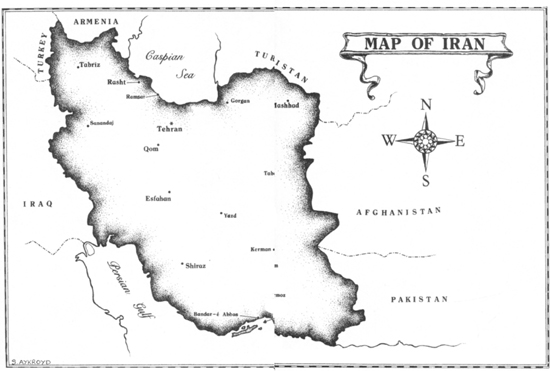

When we bought our bus tickets in Istanbul, we were told the trip to Tehranapproximately two thousand kilometres southeastcost the equivalent of twenty-five US dollars and took twenty-four hours. Wed be getting off early, in Tabriz, just over the Iranian border. About eighteen hours away, by rough calculation. We ate a big meal at the nearest food stand and spent the last of our Turkish money on a bit of fruit and bread for the journey.

Eventually, somewhere in hour thirty, we asked our neighbour in the seat behind why we were still on the Anatolian plain. He smiled and explained that twenty-four hours is the poetic time, the time it would take, say, a good car, if it drove without stopping. Maybe a German car. But you see this is an Iranian bus, with many old parts and small speed, and we will stop for toilets and praying, and then there is the border, which can be very slow. So the real time is more like two or three nights.

Khosro befriended us the moment we got on the bus in Istanbul. Excuse me, he said when he heard us speaking English. Will you travel to Iran? We nodded. He sat back and translated for his friend, Hossein. A few seconds later, Khosro sat forward again and poked his head over the tops of our seats. Excuse me, your choice it is?

We were not out of Istanbuls city limits before the first person walked to the front of the bus with a box of cookies and offered one to every passenger. A few hours later someone else offered dates, then sunflower seeds, then something that resembled candy floss. Khosro and Hossein passed bread, cheese and vegetables up to us at regular intervals. When I thanked them for the eggplant caviar, which was delicious, they insisted that we take three cans. No, four. Heres another. The old women in front of us stuck their hands through the seats from time to time, reached for my hands and filled them with nuts. The couple across the aisle handed us a bottle of orange soda every time we looked in their direction.

We were also not out of Istanbuls city limits before the bus had its first of Im not sure how many collapses. More than five. Each breakdown prompted men to get off the bus, gather around the engine with one hand up to their chin and look perplexed. Some prayed by the side of the road. I never saw anyone but the drivers do anything to the engine but stare.

The rest of us stood off to the side and got acquainted.

Khosro was in Istanbul to apply for a tourist visa to the United States. He took the bus from Tehran (poetic time 24 hours; real time 75 hours), spent two days making his visa request at the American embassy in Istanbul and is now on his way back to Tehran. His visa request was denied, but he plans to try again next year. Hossein came along to keep Khosro company. Did he enjoy Istanbul? Yes, very beautiful, though he only saw the Blue Mosque and the American embassy.

Most of the other passengers had gone to Istanbul to apply for visas to Emrika as well. No one had been successful, but most were planning to try again next year. Everyone brought at least one friend or family member along for company; one man brought six of his cousins. There was a family on holiday, several people on religious pilgrimages and a young couple returning from their honeymoon.

They were proud and nervous, this couple, awkward with each other, giddy at the idea of each other. He was older, much older, and tried to look confident. She was younger, youngmaybe fourteenand in awe of the world. They kept to themselves during the trip, spent a lot of time smiling, and spoke to each other through quick, shy whispers. Occasionally touched hands in public. Prayed at every opportunity. She was the only woman on the bus in full hejab, the covering prescribed by Islam to protect female modesty: a black floor-length coat and headscarf, folded tightly around the face, covered by a chaador, the swath of black fabric draped over the head and arms. The older women wore white veils, the colour of mourning. The younger women dressed in shirts and trousers, some in dresses, one in jeans. A handful wore headscarves.