Yet it was not consumed.

Prologue

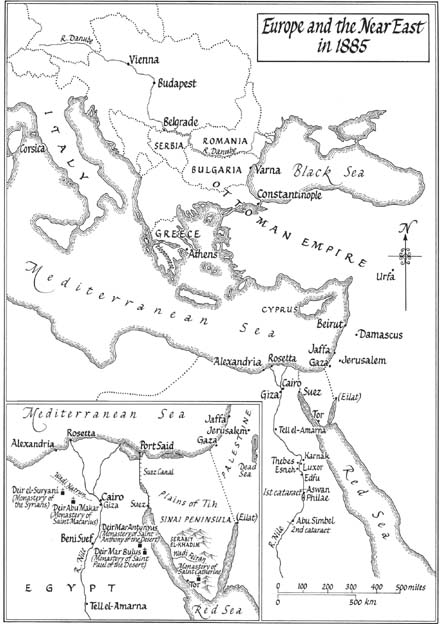

The latter half of the nineteenth century was a time of anxiety over the Bible. This concerned not only the Scriptures factual claimssuch as that the Creation had been subjected to a Universal Flood and the Israelites had fed on manna in the desertbut also bore upon the integrity of the text itself: was what had percolated down through the centuries still the same now as it was in the beginning? This uncertainty particularly affected the trustworthiness of the New Testament. Biblical scholars had long been questioning the accuracy of what was taken for granted in every pew. But from the 1850s what had been known only to a few became disturbingly public, and propaganda for those who wanted to beat the Churches. Specifically, the Greek text on which the King James Bible and many other European Bibles were based was widely known to be highly imperfect. You stand on the authority of Scripture, said the critics, but you cannot deter mine what was originally written. Although scholars were agreed in calling for a revision of the standardised Greek text, they lacked the manuscripts against which to check it. A fine early copy was known to exist in the Vatican Library, but its keepers did their best to prevent anyone from seeing it. The impasse was broken when, in 1859, Constantin von Tischendorf disclosed a biblical manuscript of unsurpassed antiquity, which he had tracked down at Mount Sinai in Egypt. On the basis of this and the Vatican manuscript, whose custodians eventually relented somewhat, two Cambridge scholars, Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort, prepared a new, authoritative edition of the Greek of the New Testament which was used by a revision committee that released a new English translation on 17 May 1881.

There was intense public interest in the new arrival. A bribe of 5,000 was offered (and refused) for an advance copy. On publication, the text was telegraphed immediately to the United States; and, in England, the Oxford University Press alone sold a million copies on the first day. Wagons waiting to take away copies for distribution jammed the London streets surrounding the printing houses.

Not everyone was pleased. The scholars declared themselves content with the Greek, but in the new translation many cherished phrasings had been lost. Most Englishmen, it was agreed, would have rather seen a revision of Shakespeare than of the King James Bible. But despite a mixed reception, it was hoped that, with an authoritative Greek text in place, uncertainties could finally be put to rest and sceptics confounded. Thus it was with considerable interest, and not a little anxiety, that in the spring of 1893 a public sensitised to the disruptive consequences of biblical manuscripts received news from the Holy Land of a major find that was almost as old as von Tischendorfs.

CHAPTER ONE

Cambridge, 13 April 1893

O n 13 April 1893, the London Daily News brought an extraordinary storyfresh from its Berlin correspondent. Two ladies, a Mrs. Lewis and her sister, Mrs. Gibson, had travelled to Mount Sinai in Egypt and discovered an ancient manuscript of the Four Gospels. Although Sinai had been searched for written treasures many times since von Tischendorf, the present discovery had remained hidden from former investigators. Professor Rendel Harris of Cambridge, on first hearing the news, had set off for Mount Sinai where, for forty days, he and the two ladies had sat in the convent deciphering the manuscript, and they were now on their way home with the results. It is a palimpsest manuscript, wrote Professor Harris in a letter to a German friend (the source of the Berlin correspondents scoop), and When Mrs. Lewis first saw it, it was in a dreadful condition, all the leaves sticking together and being full of dirt. She had steamed its pages apart with her camp kettle and, finding that the underwriting of the manuscript contained a very early text of the Gospels, had photographed the lotsome 300 to 400 pages. As to who this Mrs. Lewis and her sister might be, or what credentials they might have for the study of ancient books, the Daily News said nothing other than that both were fluent in Arabic and Greek and that Professor Harris had instructed them in the photographing of handwriting.

A further letter from Professor Harris, posted from Suez and published that very day in the British Weekly, had the same exciting story, but an equally frustrating lack of explanatory detail. It was left to the Cambridge Chronicle of the following morning, in its coverage of the breaking story, to say that as our readers are aware, Mrs. Lewis is the widow of the Rev. S. S. Lewissufficient information to identify the two ladies to the insular world of 1890s Cambridge.

An undergraduate, cracking open his Cambridge Chronicle in the Central Coffee Tavern, might recognise the Reverend S. S. Lewis as the very recently deceased Latin tutor at Corpus Christi College, and suppose his widow to be one of the two remarkably similar-looking ladies often to be found awaiting him at the college gates.

The shopkeepers on the Kings Parade could report to customers that they were indeed well acquainted with Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Gibson, for few Cambridge ladies had Paris frocks and bonnets, let alone a private coach and coachman. The two were alike in most every waytrimly built, not in their first youth, but fine-looking and energetic, with brown eyes and chestnut hair piled on their heads la mode. They would often stop by for gloves, hats or hose, ordering their goods in brisk Scottish accents, and not occasionally countermanding each other as they spoke. The two ladies had been prominent features of the town for the last few years as well as good customers, recently fitting out a grand house they had built for themselves at the foot of Castle Hill.

Members of the towns Presbyterian congregation remembered well the first appearance amongst them of the two sisters in January of 1887, both wrapped in furs and one in deep mourning. They were twins and alone in the world and, it was said, very learned. Their father was reputed to have settled an enormous fortune on them, on condition that they never live apart from each other.

The residents of the fine, newly built houses of Harvey Road recalled Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Gibson living briefly there while the largesome said pretentioushouse at Castle Hill was being built. It was reported that they had astonished their neighbours by taking exercise on parallel bars in their back gardenin their bloomersand that their new house avoided the cause of this distress by incorporating a tower with gymnastic ropes so that the two sisters could exert themselves in privacy.

Many knew that the two ladies were keen travellers, but few imagined they would venture as far as the Sinai, a region known to be rugged and dangerous and where, only ten years before, the universitys Professor of Arabic had been murdered by bandits.

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE