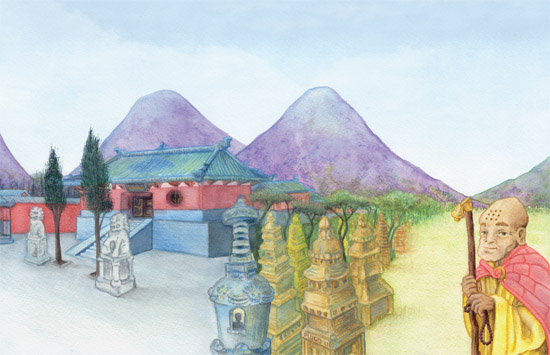

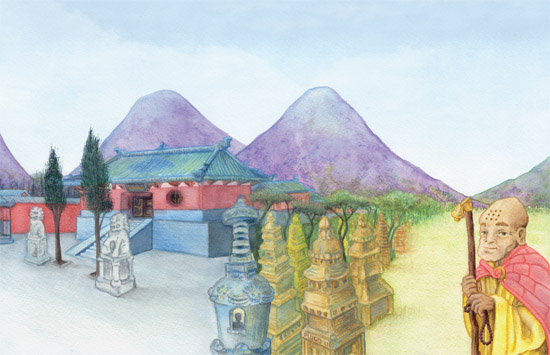

L ong ago in Old China, at the foot of Song Mountain, sat a quiet place called the Shaolin Temple. Shaolin was a monastery where monks lived in peace, tending to gardens and praying by candle and leaving no tracks where they walked. There were student monks, big brothers, uncles, and the master monkswise old men like Master Feng.

And then there was Wong Long, the small orphan boy who was left on the steps on a long night in the Year of the Monkey.

Wong Long loved his life in Shaolin Temple. He loved lighting the incense for Master Feng; he loved feeding the birds and learning their songs as he walked the mountain trails to gather tea leaf. He even liked sweeping snow from the temple steps. But mostly he loved Kung Fu.

Kung Fu, said Master Feng, is a gift from our grandfather monks, an ancient secret that we practice to keep our minds at peace and our bodies strong.

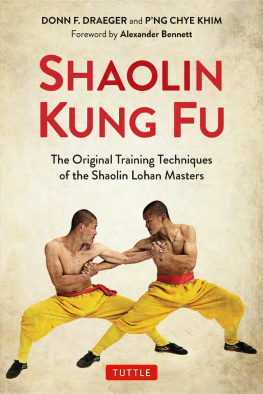

Wong Long knew that his beloved temple had been burned down by bandits and raiders many times in the past. But the monks always forgave the enemy and rebuilt their walls. They did not want to fight, only to defend the child monks and the old ones and the pagodas where they buried the priests. For all life was sacred to a Shaolin monk. Wong Long was taught that the secret ways of Kung Fu were hidden deep in nature. Each monk chose an animal style and studied the ways of that creature so that he might move like it and understand its being and become part of nature as he practiced. This was called the

Five Animal styles of Shaolin. It was said that it took half a lifetime to master even one animal.

And so the monks would practice. Practice. Practice. And practice. And when they were done at the end of each day, Master Feng would say, Practice some more.

L ike painting or music, it was beautiful art. Kung Fu, said Master Feng, does not mean fighting. It means accomplishing a skill through hard work over time. A masterful gardener could be said to have good Kung Fu. A flute player who has studied well can have good Kung Fu. So can a cook, or a mother of children, or the man who carves walking sticks.

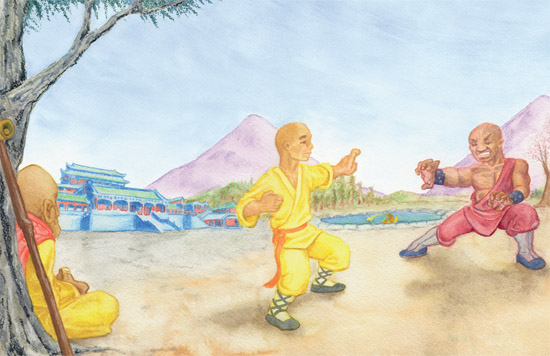

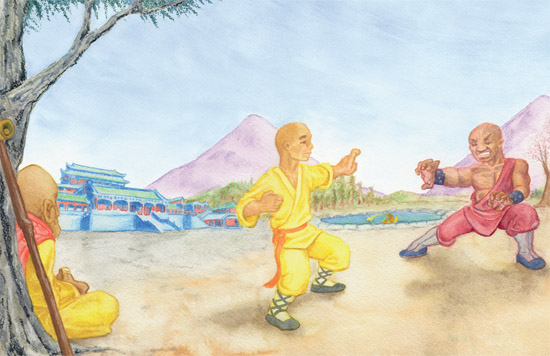

On the day of the First Plum Flowers of the Spring Wind, Master Feng called Wong Long to the courtyard to observe his martial art. He also summoned Brother Zhu and both young monks bowed deeply to the old master and then to each other, for respect was part of the Kung Fu code.

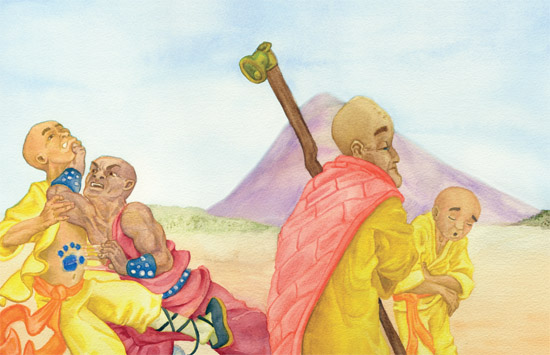

Some day, said Master Feng, the Manchus may come again and attack us while we pray or tend to the gardens. We will always ask them to leave and offer them food. But if they do not leave and insist on harming us, we must stand up and defend what is right.

Master Feng sat on the soft earth in the shade of a cypress tree and was quiet for a time. Show me what you have learned, he said.

Wong Long took his fighting stance. Brother Zhu did the same. It was now time to spar. Brother Zhu moved first. A student of Tiger Style, he held his hands like mighty paws and made his stance rooted yet light. The Tiger style was the way of strength and inner power and Brother Zhu let that force flow through him.

L ike a jungle king he whirled and he twirledHe unfurledTIGER CLAWS! And when Wong Long tried to strike him he was not therebut behind him! He appeared so big and strong to the littlest monk that fighting back seemed useless. Still, Wong leapt into the air and launched a powerful kick.

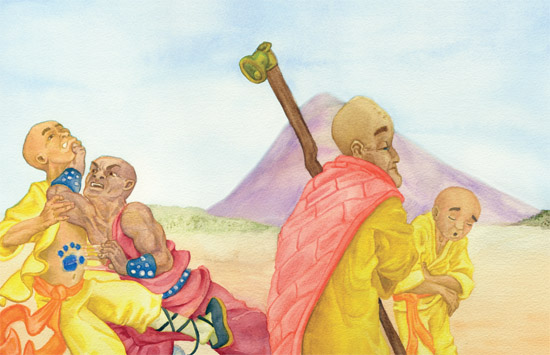

But Tiger Way does not defendOne swift attack will bring the endSee him bendinto stripes and tailor so it seemed to Wong Long who was no longer fighting a student, but a real tiger! What happened next he could not remember. For he was on the ground, looking at the sky, hardly able to breathe.

Brother Zhu, student of the Tiger Style had defeated him. When it was over, the senior brother helped Wong Long to his feet and then bowed to him. Wong Long felt shame, but he returned the honor.

There is no shame. This is how we learn, said Old Feng. Brother Zhu has listened to the ancient voice of nature. You must practice more.

Yes, Master, said Wong Long.

T hat night, Wong Long sat by the two candles in his tiny room near his sleeping mat. Monks did not keep much, for it was the way of a monk to live spare and not want for things. But Wong Long kept one possession that had belonged to his mother. It was a small and delicate bamboo bird cage that he would sometimes take from the window sill and admire. Sometimes he would imagine the song bird it once held, and he would try to remember his parents before they were lost to the Fever and he was taken in by his uncle. It was whispered that Wong Long had become angry when he lost his parents and hed become hard to manage. And so his uncle had left him at the Shaolin Temple, hoping that the monks would take pity on a child.

Now Wong Long looked out his window at the night sky and saw the Seven Stars.

When he thought about how many people around the world could see the same stars it made him dizzy. The world was a big place and uncertain. He felt safe high up on the mountain in Shaolin Temple with his brother monks and the kind old masters and the smell of incense and spices.

Yet he felt unworthy. He was too small and did not feel as smart as the other students. He wondered if that was why his uncle left him on the steps and never looked back. He tried hard to learn martial art, but he was always defeated in the matches. What good was heto anyone?

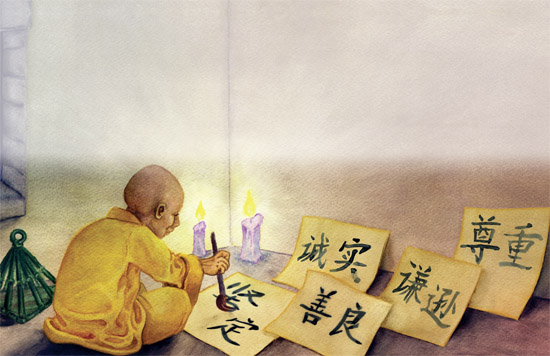

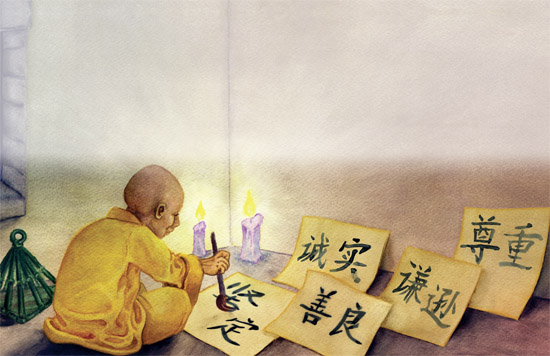

Sitting in his room and looking at the Seven Stars, he wanted to cry. Instead, he took up his brush and silk, and painted the Chinese characters for the Kung Fu Code:

RespectTo consider yourself and others worthy of high regard.

HonestyTo be truthful.

KindnessTo be gentle and helpful.

HumilityNot to think or consider yourself better than others.

PerseveranceTo continue despite opposition, hardship, or discouragement. To never give up.

As he carefully painted each character, he felt his tears disappear like clouds split by the sun.

Perseverance, he whispered to himself. I must not give up.

T he next day, and for weeks after, the little monk observed Brother Zhu and the Tiger Way. He spent hours in his low stances, developing strong legs and the inner force from deep down in the belly called chi. And when he meditated in the quiet gardens, he thought for hours of Tigers strong bones but fluid grace and what it teaches a human. It is like the Yin and the Yang, he heard Master Feng tell Brother Zhu. The hard turns into the soft, and the soft turns into the hard. There cannot be one without the other just as there can be no light without the darkness before. All things contain their opposite. That is the Yin and Yang.

Soon it felt so good in practice, that he ROARED when he threw his palms out and SCREAMED when he threw his spinning kicks. Im King of the Beasts! he shouted out one day and the senior students chuckled.

He felt ready when Master Feng summoned him to the yard on a chilly morning. Waiting there was Brother Ming, as tall and willowy as bamboo. He and the smaller monk bowed deeply to Master Feng and then to each other.