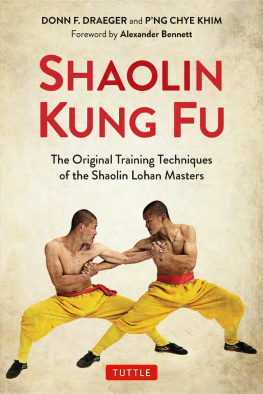

MANY PEOPLE were responsible for making this book possible, some more directly than others. We extend our gratitude to all who contributed so generously of their time and experience while this book was being prepared. Special thanks go to Yuk Yin, priest of the Song Kheng See in Penang and patron of the Hood Khar pai; to Chew Ah Pee and Lee Ah Choo, who served as the models, together with the Chinese coauthor, for many of the illustrations of training exercises and techniques; to Khoo Kay Chee, who translated the technical portions of the text; to Pye Ling Shan Rur, who painted the likeness of Ta Mo, and to Shi Mit Tu, who was the calligrapher for the painting; to D'Arcy Champney, whose skillful artwork heightens the explanations of fundamentals and techniques; to Kobayashi Ichiro and the members of his photographic staff for the special care taken in preparing the photographic illustrations; and to Gail Brooks, who typed the final manuscript.

Background of Shaolin

Legend

Oral tradition tells us that about A.D. 520 an Indian Buddhist monk arrived in China. He eventually settled at the Shaolin Temple at Sung Shan in Honan province. This monk was P'u-t'i-ta-mo, or Ta Mo (Bohdidharma), as he is more popularly known. It is said that the original Shaolin Temple ( Shaolin-ssu ) was located just below the peak and on the northern side of Sung Shan, one of the great mountains in Honan. This temple was allegedly built by Emperor Hsiao Wen of the Northern Wei dynasty (A.D. 386-534).

Ta Mo introduced some very conservative Buddhist doctrines at the Honan Shaolin Temple, as he was opposed to the highly ritualistic and extravagantly ceremonial religious practices that he found there. He held that the practice of sitting in solitude for the purpose of meditating was the core of a superior kind of religious Buddhism, and in support of his belief he allegedly sat in meditation for nine years while facing a wall in the courtyard of that temple. Ta Mo's kind of Buddhism is said to be the basis of what is today known as Ch'an, and he is considered its First Patriarch.

At the Shaolin Temple in Honan, Ta Mo became disturbed over the fact that monks there frequently fell asleep during meditation. He thereupon designed special exercises by which the monks could increase their stamina and so stay their weariness. In the I-Chin Ching (Muscle-Change Classic), a work that is attributed to Ta Mo, we find described and illustrated eighteen such basic exercises for the purpose of improving one's general health. These exercises are believed by some people to be the basis of shaolin, a category of hand-to-hand arts, so named after the temple at which Ta Mo meditated.

Thereafter, the Honan Shaolin Temple attracted men from all walks of life, and became a source of and training ground for persons who engaged in the practice of fighting arts. Many of the exponents of fighting arts who trained at the Honan Shaolin Temple became involved in the political intrigues of the various Chinese dynasties that were constantly seeking to become the absolute ruler of China. For example, during the T'ang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), heroic fighting monks such as Chin Ts'ao, Hui Yang, and T'an Tsung of the Honan Shaolin Temple were instrumental in the T'ang defeat of the rebel Wang Shih-ch'ing.

A second Shaolin Temple, supposedly constructed over a thousand years ago at Chuan Chow in Fukien province in South China, is also recorded in Chinese legends. A Buddhist priest named Ta Tsun-shen is believed to have founded it. This temple, too, eventually became a center for combative activity, and consequently is said to have played an important role in the political histories of various dynasties.

Both temples, the one at Sung Shan in the north and that at Chuan Chow in the south, were, during years of warring, frequently razed on the grounds of alleged sedition against the government. Only a few of the occupants of these temples managed to escape the wrath of the imperial troops sent to destroy them. The more fortunate of these fugitives avoided detection by going their separate ways to other areas of China and elsewhere, where they continued their study and practice of fighting arts.

The fame of the Fukien Shaolin Temple became particularly widespread as exponents of combative arts converged there to further their skills. The Ch'ing (Manchu) government (1644-1911) was grateful to this temple when, during the reign of Emperor K'ang Hsi (1672), 108 Shaolin Temple monks volunteered for military service against the marauding bands of barbarians who were massing on China's western borders. These monks displayed skill and heroism in expelling the invaders. But a short time later, when it was discovered that the Fukien Shaolin Temple monks were actually rebels who dreamed of restoring the Ming government and who were searching for an opportunity to launch their own uprising, the Ch'ing ordered the destruction of the Fukien Shaolin Temple and the massacre of its occupants. Five monks, later honored as the Five Early Founding Fathers, escaped by hiding under a bridge, and were taken into hiding by five brave men who were subsequently referred to as the Five Middle Founding Fathers. In turn, these ten rebels were joined by five other monks, the Five Later Founding Fathers, and together with the priest Wan Yun-loong (Ten-Thousand-Cloud Dragon) and Ch'en Chin-nan (Great Ancestor), did battle against the Manchu forces in the northern province of Hopei. The spirit of their uprising spread rapidly southward and inspired others to join in the fight against the Manchu government. Each of the five original monk fugitives from the Fukien Shaolin Temple is believed to have established his own particular kind of shaolin, and collectively these five kinds of shaolin are traditionally held to be the prototypes of shaolin as we know it today.

History

Most of what is traditionally said about the Shaolin Temples is unconfirmed and unverifiable ; it is the basis of endless variations on colorful but highly improbable happenings such as form the bulk of plots of Chinese folklore and the dramatized versions of heroics that take place on the modern Chinese popular stage. But, because there may be some factual basis for even the most exaggerated of these stories, modern exponents and scholars of Chinese hand-to-hand arts continue their efforts to discover the truth about the Shaolin Temples and their effect on Chinese society.

The traditional date of Ta Mo's arrival in China (c. A.D. 520) is suspect; recent investigations made by historians indicate that he may have come to China as early as A.D. 420-79. We know little beyond the facts that he actually lived and that he came to China. There are no historical records of his existence in India. Further, there is no proof of his authorship of the Muscle-Change Classic ( I-Chin Ching). Nor are the eighteen basic exercises in that book directly related to Chinese combative arts, being more concerned with calisthenics performed from static stances and postures and designed to strengthen the body and mind so that the performer will be more receptive to meditative discipline. It is now known that combative arts of a shaolin-like nature existed long before Ta Mo came to China, and that at least some of these arts were initially practiced in places other than the Shaolin Temples. Scholars, therefore, generally agree that Ta Mo did not introduce shaolin methods to China.