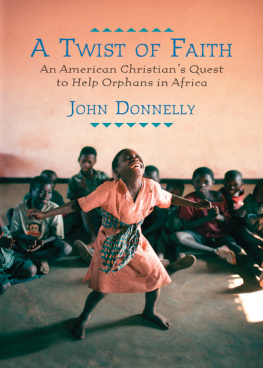

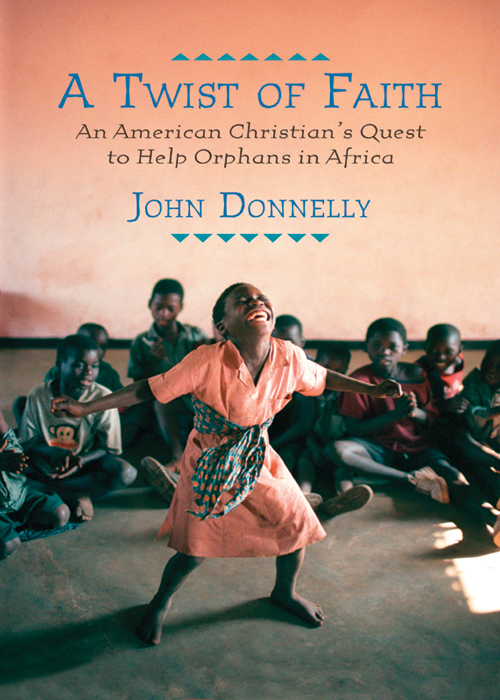

To my parents, Michael and Mary Donnelly,

and to my mother-in-law, Lois Markt,

for raising children well.

Chapter 1

A Moment in an African Field

T his was all new. The country, the people, the big sky, the red-clay road that was so narrow it seemed to have been built for bicycles. Just being in Africa made him want to praise the Lord, which he did frequently and with great feeling. David Nixon Jr., an evangelical Christian and a do-it-all carpenter from a suburb of Charlotte, North Carolina, couldnt have been more excited, or more on edge, as he rode in the back seat of a long white Toyota Hiace van into the African bush.

He was traveling deep into the backcountry of a nation he had first heard about only months beforelandlocked Malawi in southeastern Africa. He was in the middle of nowhere as far as he was concerned, about an hours drive west of Lilongwe, the countrys quiet capital. And he was with five fellow American missionaries, including two friends who, like him, were on their first trip to Africa. They had all come in the middle of the summer in 2002 with a loose plan to find local churches and work with them to help orphans. The six of them werent sure if that meant contributing money and whatever expertise each of them had to offer, or if it meant diving in and doing it all themselves.

Nixon was of average height and weight: five foot eight, 165 pounds. He shaved his head every day so close that his scalp shone, a habit he had begun a decade earlier when hed spent months living in a tent, studying the Bible, and trying to figure out how he would follow Gods word. He had strong arms, a broad chest, a linebackers shoulders, a booming baritone voice, and eyes that could be as playful as a childs or as stern as a drill sergeants. He was not good at hiding his emotions. When he was having a good day, he was full of energy and vim, ready to attack life. When troubles got him down, his shoulders slumped as if he were Atlas carrying the weight of the world. Those dark moods would come and go, but they didnt stay as long as they had when he was a young man hounded by trouble. He attributed the elevation of his mood to his trust in God. God was his Father, and when Nixon said grace, he praised God so thoroughly that the food would often get cold.

On this day in a field in Malawi, he felt vaguely like one of those explorers from a distant era. But he and his partners werent looking for gold or diamonds, or for tribes that had had little contact with the outside world; they were hunting for a community in dire need of help. These men knew every community could use some assistance, so they needed to find a local organization they could feel comfortable with to act as their on-the-ground contact. They believed fervently they had to do all the good they could do for poor Africans, the polar opposite of the goal of most of those whod come before them, decades and centuries earlierpeople who wanted to pillage the continents riches or enslave its inhabitants.

Their mission couldnt have come at a more urgent time. According to estimates put forth by the United Nations, in recent years the number of orphans in Africa had grown to 34 million, a huge jump from a decade before, due to the AIDS pandemic, which had hit sub-Saharan Africa with greater force than anywhere in the world. In 2002, AIDS treatment was available to people in wealthier countries but to only a tiny percentage of HIV-positive people in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Just fifty thousand out of the millions of HIV-positive people in developing countries were receiving life-extending treatment. As a result, mothers and fathers in Malawi and throughout Africa were dying at alarming rates. Every day across Africa, relatives carried thousands of their near-to-death loved ones to hospitals that had no supplies or medications to save them. Hospital morgues stacked bodies in refrigerated and unrefrigerated rooms. The international community was just beginning to mount a response to this humanitarian emergency, forming the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in 2002; in 2003, the Bush administration committed billions of dollars to an ambitious program called the Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR.

But government programs and the continued work of well-established charities and nongovernmental groups that had labored for decades to deliver aid on behalf of wealthy nations werent the only responses. Mostly hidden from public view and rarely recorded or tracked by government or independent evaluators, thousands of private American groups, the vast majority of them faith based, were stirred to action. According to academics who studied development assistance, those faith-based groups gave several billion dollars a year to African causes, a stunning amount that likely surpassed the contribution of the U.S. Agency for International Developments funding of African projects.

Over the past decade, Ive often crossed paths with this underground movement of mostly untrained aid workers who arrived in countries across Africa. Five years ago, I decided to take a much closer look. In the fall of 2007, supported by a global-health reporting fellowship from the Kaiser Family Foundation, photographer Dominic Chavez and I started to document what exactly was going on with the torrent of American do-gooders traveling around Africa to help children. I wanted to determine if these disparate efforts were making any difference, either positive or negative. I decided to go to Malawi first, a country I knew well from previous visits for my newspaper, the Boston Globe. And from the moment I started my journey, I saw American do-gooders everywhere. They were on every plane trip I took. In African countries, I ran into them at shopping malls, in government offices, in bars and restaurants at the end of long days. Usually within the first ten minutes of conversation, they brought up their deep Christian faith. More often than not, they extended an invitation for me to come see their work firsthand.

I also spent hours with the U.S. embassy employees who were the architects of the massive American response to fight AIDS. These were some of the most dedicated government workers I have ever met. In the early days of the PEPFAR initiative, they all seemed to work sixty or seventy or eighty hours a week. They were so dedicated because they knew the better the job they did, the more lives theyd save. There was no doubt in their minds. How could there be? If you lived in sub-Saharan Africa in 2003, all you had to do was go to a morgue or a coffin makers shack or the adult wing of a city hospital to be confronted by the inescapable truth: AIDS was destroying the population of young adults in Africa. The PEPFAR workers were fascinated by, and sometimes more than slightly uneasy about, all the private Americans from faith-based groups who were requesting information or showing up at embassies asking how they could help African children. Several longtime U.S. foreign-service officers estimated that the number of private do-gooders was two to three times higher than it had been in the 1990s.

As the members of these faith-based groups boarded planes for faraway destinations like Lilongwe, Addis Ababa, Nairobi, and Dar es Salaam, they imagined themselves building orphanages. Some of them anxiously awaited the culmination of months of planning to be allowed to adopt parentless children. David Nixons group from Monroe, North Carolina, was, in many respects, not so different from thousands of others. They were people with big hearts and big ideas. But like many of the others, they came without much else: without knowledge and, perhaps, without enough humility.