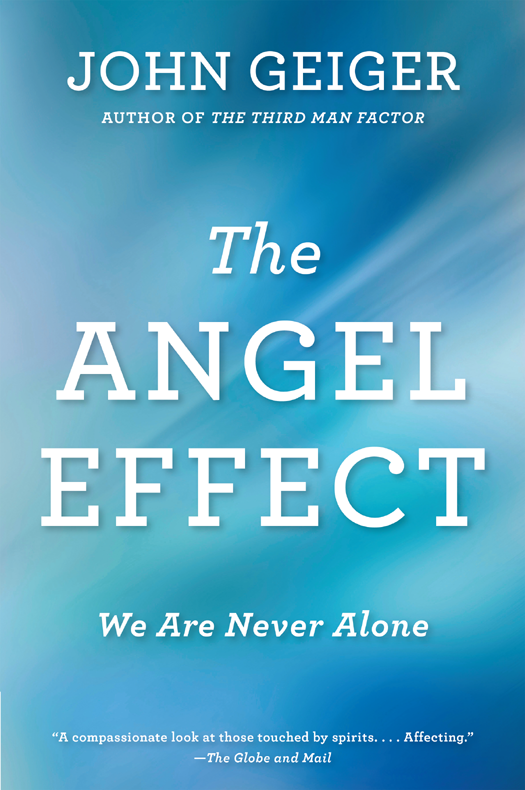

THE

ANGEL

EFFECT

WE ARE NEVER ALONE

JOHN GEIGER

FOR MARINA

In 2008 I experienced something extraordinary at a moment of great pain, something that has altered the way I think about the world and has given me firsthand insight into a profound mystery.

It happened to me when I had nearly completed writing The Third Man Factor: Surviving the Impossible, and it brought the phenomenon of what scientists call the sensed presence vividly to life for me. That book arose from my growing realizationgleaned from my own experiences in the Arctic, my conversations with explorers and field scientists, and reading the published accounts of explorersthat people under enormous stress, sometimes at the edge of death, often experience a sense of an incorporeal being beside them who encourages them to survive. Climbers refer to it as the third man.

I assembled a trove of such stories and investigated religious, psychological, and neurological explanations for the phenomenon. In the process I also published a scholarly study, The Sensed Presence as a Coping Resource in Extreme Environments, with Professor Peter Suedfeld, a renowned expert of the psychological effects of exploration who has also advised NASA.

Suedfeld and I identified four indisputable facts about the sensed presence, notably that they occur to otherwise mentally normal, physically healthy individuals; they arise in stressful situations; they serve as a coping resource in that

The sensed presence is far greater than the simple feeling that we all sometimes have when, alone at night or when walking down an alley, we feel that someone is there. Various reductive explanations have been offered, and although many of those indeed may play some role, none of them comes anywhere near to capturing the richness and profundity of the experience, which person after person describes as among the most important of their lives. Peter Suedfeld and I argued for the need to better understand the dramatic helpfulness of the sensed presence, which includes not only encouragement, but also factual information and, on occasion, physical intervention.

That study, and The Third Man Factor, held closely to the view that you had to be astride Everest or engaged in an equally harrowing pursuit, such as those undertaken by solo sailors, polar explorers, and astronauts, to experience the phenomenon. It worked wonderfully as a way to introduce the radical idea. But in fact, it is not the case that explorers and adventurers are the sole recipients of such interventions. Far from it.

I opened The Third Man Factor with the experience of Ron DiFrancesco, the last person to escape the South Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11, who told me that he survived that day because an angel helped him. DiFrancesco was just going about his routine business when terror struck. He found himself trapped in a smoke-filled stairwell, above the point of impact of United Airlines Flight 175, with flames and a collapsed wall obstructing his escape. Other people were with him on a landing, some apparently unconscious, when, he says, an angel urged him to carry on. It addressed him by his first name and gave him encouragement, telling him, Hey! You can do this.

DiFrancesco felt that he was literally helped to his feet and then guided on, saying, It led me to the stairwell, led me to break through, led me to run through the fire. There was obviously somebody encouraging me: Thats not where you go, you dont go toward the fire. He covered his head with his arms and literally fought through it. He believes the flames continued for three stories. Only after he got safely through the debris, to below the flames, did he sense the angel leave. It had been with him for five minutes. When talking to him, I was struck by the idea that something extraordinary can touch everyday people caught up in crisis situations they werent looking for or were in anyway prepared for.

Then, following the publication of that book, hundreds of people began to step forward with their stories, accounts that do not involve high-altitude climbsthough I do still get plenty of those. Intriguingly, however, these stories often include quite routine stresses, the sorts of hardships that we all potentially face in our lives when confronted by grief, physical and sexual assaults, automobile accidents, raging fires, and bank heists as well as a result of long illnesses, the pain of childbirth, the despair of alcoholism, and even in cases of persistent loneliness.

Others sent me testimonials handed down from loved ones who had served in war or survived other personal calamities. They wrote to me from Australia, the UK, Spain, the United States, and Israel, and they were men, women, teenagers, and seniors. Some of my friends and acquaintances also came forward to say it had happened to them. These stories are every bit as compelling as those of the explorers and adventurers. This phenomenon is universal; it can happen to any one of us.

And then it happened to me.

J AMES ENTERED OUR LIVES AT 1:26 A.M. on Friday, June 15, 2007, three minutes after his brother Sebastian. Despite a diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a rare congenital heart condition first detected in an ultrasound, he declared himself a strong little boy, very much a fighter. He was fine when inside my wife, Marina, and indeed he had thrived, surprising us by coming in at four pounds, nine ouncestwo ounces heavier than his older brother.

J AMES ENTERED OUR LIVES AT 1:26 A.M. on Friday, June 15, 2007, three minutes after his brother Sebastian. Despite a diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a rare congenital heart condition first detected in an ultrasound, he declared himself a strong little boy, very much a fighter. He was fine when inside my wife, Marina, and indeed he had thrived, surprising us by coming in at four pounds, nine ouncestwo ounces heavier than his older brother.

He was a gorgeous baby. He looked normal; in fact, he was normal in every other way, but basically James had half of a heart, as his left ventricle was severely underdeveloped. From the moment of his birth the clock started ticking.

We had been trying to have a second child for five years. After our first was born, Marinas obstetrician said that if we wanted another, we should not delay, that time was not our friend. But the demands of new parenthood overwhelmed us so much that we set aside the thought of immediately having another child.

By the time we were ready, the ground rules had changed, and we needed fertility treatments. Finally, after much effort, we produced a pregnancytwin boys. This was joyous news, but the very serious diagnosis that an ultrasound delivered after twenty weeks soon tempered our happiness.

Among the options presented to us was the selective termination of the second fetus, a procedure that would also have had a slight risk of jeopardizing the healthy child. Even without the risk to the other twin, it was an unacceptable option for us both. We opted to see the pregnancy through, bracing for the trauma that lay ahead. We read everything we could find about the condition. We met with a couple who had a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and whose son was doing quite well given the severity of the medical journey he was on. The boy was in school. Looking at him you wouldnt know, they said. But we also understood that his was an exceptional case.

The twins were born prematurely, and this further complicated Jamess condition. At his birth, James cried briefly, the only noise I ever heard him make. He was literally rushed from the delivery roomeach was. The two boys were then immediately placed in separate incubators. I was unable to photograph them together. Shortly after their birth James was whisked away to the Critical Care Unit at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Sebastian remained across the street in the Intensive Care Unit of Mount Sinai Hospital. Marina was also hospitalized for several days.

J AMES ENTERED OUR LIVES AT 1:26 A.M. on Friday, June 15, 2007, three minutes after his brother Sebastian. Despite a diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a rare congenital heart condition first detected in an ultrasound, he declared himself a strong little boy, very much a fighter. He was fine when inside my wife, Marina, and indeed he had thrived, surprising us by coming in at four pounds, nine ouncestwo ounces heavier than his older brother.

J AMES ENTERED OUR LIVES AT 1:26 A.M. on Friday, June 15, 2007, three minutes after his brother Sebastian. Despite a diagnosis of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a rare congenital heart condition first detected in an ultrasound, he declared himself a strong little boy, very much a fighter. He was fine when inside my wife, Marina, and indeed he had thrived, surprising us by coming in at four pounds, nine ouncestwo ounces heavier than his older brother.