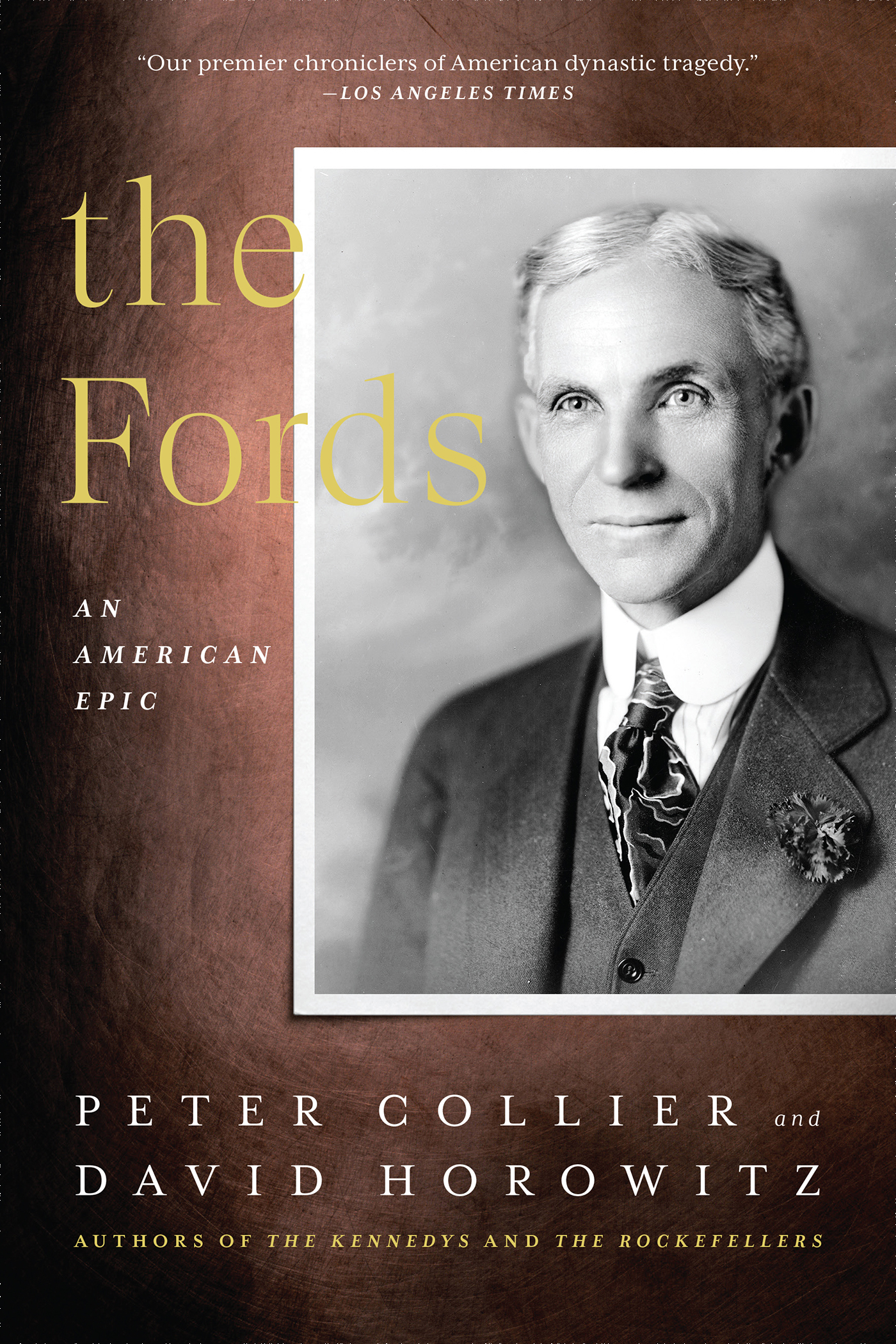

THE

FORDS

AN AMERICAN EPIC

Also by the authors

THE ROCKEFELLERS

An American Dynasty

THE KENNEDYS

An American Drama

DESTRUCTIVE GENERATION

Second Thoughts about the Sixties

THE

FORDS

AN AMERICAN EPIC

PETER COLLIER

DAVID HOROWITZ

ENCOUNTER BOOKS

NEW YORK

Copyright 2021, 2002, 1987 by Peter Collier and David Horowitz

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

Second American edition published in 2021 by Encounter Books,

an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc.,

a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States and printed on acid-free paper.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

First paperback edition published in 2002.

First paperback edition ISBN: 978-1-89355-432-0

Second paperback edition published in 2021.

Second paperback edition ISBN: 978-1-64177-191-7

Second paperback edition eISBN: 978-1-64177-192-4

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

CONTENTS

I T WAS AFTER MIDNIGHT when a light summer mist started to fall outside the backyard workshop and Henry Ford began putting the final touches on the peculiar-looking machine which had obsessed him, in one form or another, all his adult life. On most other evenings, Felix Julien, the old man who lived in the flat next door to the Fords and had cleared out his half of the shed to give the machine more space to grow, would have been there, too, sitting in a corner of the shed, watching the painstaking assembly in silent awe. In fact, Ford had often arrived home from his daytime job as chief mechanic at Detroits Edison Illuminating Company to find Julien sitting alone in the shadows, staring at the odd contraption slowly taking shape, impatient for him to hurry through dinner and get to work. But now, on this night of nights, the old man had unaccountably decided to go to bed early and so he missed the last act of the great drama.

It was almost 2 A.M. when Henry and his friend Jim Bishop finished work. Although he was haggard from having gone two nights without sleep, Fords recessed gray eyes flashed with excitement. His invention was finally ready for a test. But as he began to maneuver it toward the door there was a revelation of the myopia everyone who knew him accepted as a paradoxical part of his visionary nature: the machine was too big to fit through the doors of the shop. Without hesitating, Ford seized a maul and began to knock out an opening in the brick walls.

Henry rolled the vehicle he later referred to as the baby carriagea light chassis on four bicycle wheelsout into the night. The metaphor came naturally: it was as if the womb of his creativity, gravid since boyhood, was finally opening. Ford would tell what happened next thousands of times in the coming years, never tiring of the repetition and always speaking in the tones of wonderment most men used to describe the birth of their firstborn. As it became worn smooth with frequent retelling, the story eventually came to have the understated simplicity of a Creation myth:

It was raining. Mrs. Ford threw a cloak over her shoulders and came outside. Mr. Bishop had his bicycle ready to ride ahead and warn drivers of horse-drawn vehiclesif indeed any were to be met with at such an hour. I set the choke and spun the flywheel. As the motor roared and sputtered to life, I climbed aboard and started off. The car bumped along the cobblestones of the alley, as Mr. Bishop rode ahead on the bicycle to warn any horse-drawn vehicles. We went down Grand River Avenue to Washington Boulevard. Then the car stopped. We discovered that one of the ignitors had failed. When we had repaired it, we started the car again and drove back home. Both Mr. Bishop and I went off to bed for a few winks of sleep. Then Mrs. Ford served us breakfast and off we went to work as usual.

The following day Henry took his wife for her first ride. Clara Ford had sacrificed, too, during the past few years, begging the neighborhood hardware store to increase its fifteen-dollar limit on credit purchases so that her husband could buy nuts and bolts, occasionally helping with his experiment on the gasoline engine, and worrying about his health as he worked in the freezing backyard shop night after night. Now she climbed up onto the narrow seat of the machine grimly clutching their two-year-old son, Edsel, her prim round face and heart-shaped mouth almost obscured by her bonnet and veil. By the time they had returned from the harrowing trip over the cobble-stone streets, their landlord, William Wreford, was standing in front of the Bagley Avenue house, indignant at the damage that had been done to the backyard shed the night before. But after Henry showed him the horseless carriage and breathlessly explained its wonders, Wreford was so completely won over that he not only rejected Fords offer to repair the damaged brick but insisted that the opening be widened to allow the quadricycle easy entry and exit.

The rest of the week Ford drove all through Detroit. Jim Bishop bicycled ahead of him as a flagman, stopping at saloons and stores to tell people to come out and hold their horses. One day the little vehicle knocked a man down; by the time Ford had turned off the engine and climbed down, the victim lay on the ground, caught between the front and rear wheels. Ford leaned over and discussed the problem with him. Should he start the engine again and finish driving over him, or should he try to move the car? Finally another man appeared and helped Ford pick up the quadricycle and move it off the prostrate man, who stood up, dusted himself off, accepted Fords apologies, and walked off, victim of the first recorded auto accident.

Seeing the strange little car coughing and wheezing along the narrow streets during the next few days, people would sometimes yell out the nickname his obsessive drive to build a horseless carriage had earned FordCrazy Henry! But whenever he stopped, crowds immediately surrounded his invention, examining it with such enthusiasm that he finally had to begin chaining it to lightposts for fear they would carry it off. Yes, crazy, he sometimes said, tapping his temple with a forefinger. Crazy like a fox.

On the first weekend after the birth of his car, Henry drove out to the family farmstead where he had been born, Clara sitting beside him holding Edsel, who still wore babys dresses. The deep ruts worn into the road during the spring rains had not yet been filled in and the little car tilted, the wheels of one side sinking down in the tracks worn by wagon wheels, while those of the other side rode higher up on the center of the road. With several stops along the way to adjust the engine, the ten-mile trip took better than an hour. When they arrived, Clara and Edsel dismounted so that Henry could give rides to his family. One of his sisters, Margaret, always remembered the great speed and the sense of bewilderment she experienced while in his car, although after the ride was over she felt that this was just another interesting toy her clever brother had built.

The only one who refused a ride was Henrys father, William. His sons desertion of the farm had been a disheartening experience for him. Unlike his brothers, Henry seemed incapable of settling down, because of the obsession with the horseless carriage; at thirty-three, he was already on the edge of middle age, a failure by his fathers definition and by anyone elses except his own. William Ford stood silently in the doorway watching the noisy vehicle kick up dust. Soon neighbors began crossing the fields to see what was causing all the commotion; eventually a dozen or so were standing there looking laconically at the car and then sympathetically at William Ford as if commiserating with him for Crazy Henrys strange behavior.

Next page