Published by Stackpole Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2021 by Claire E. Swedberg

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Swedberg, Claire E., author.

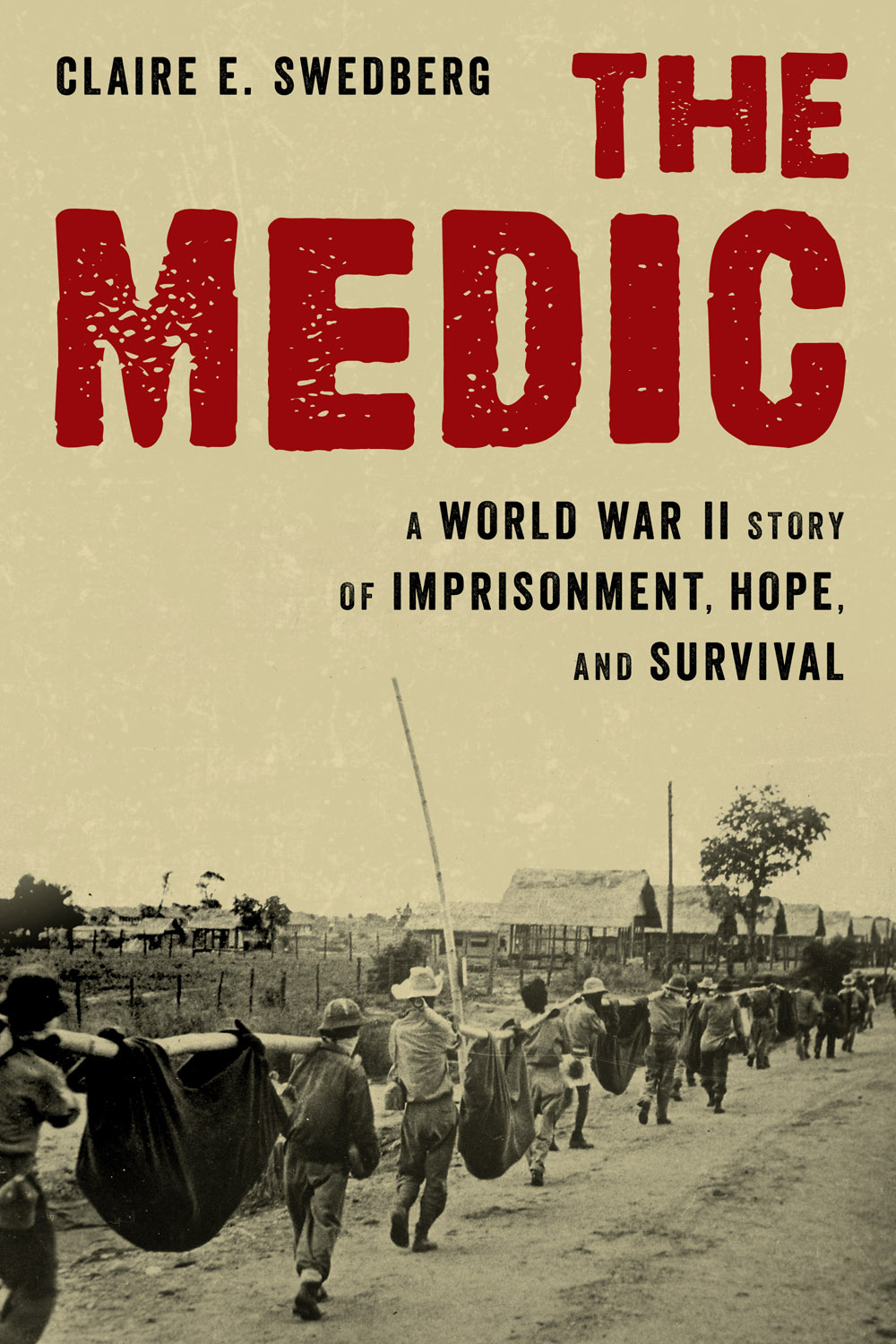

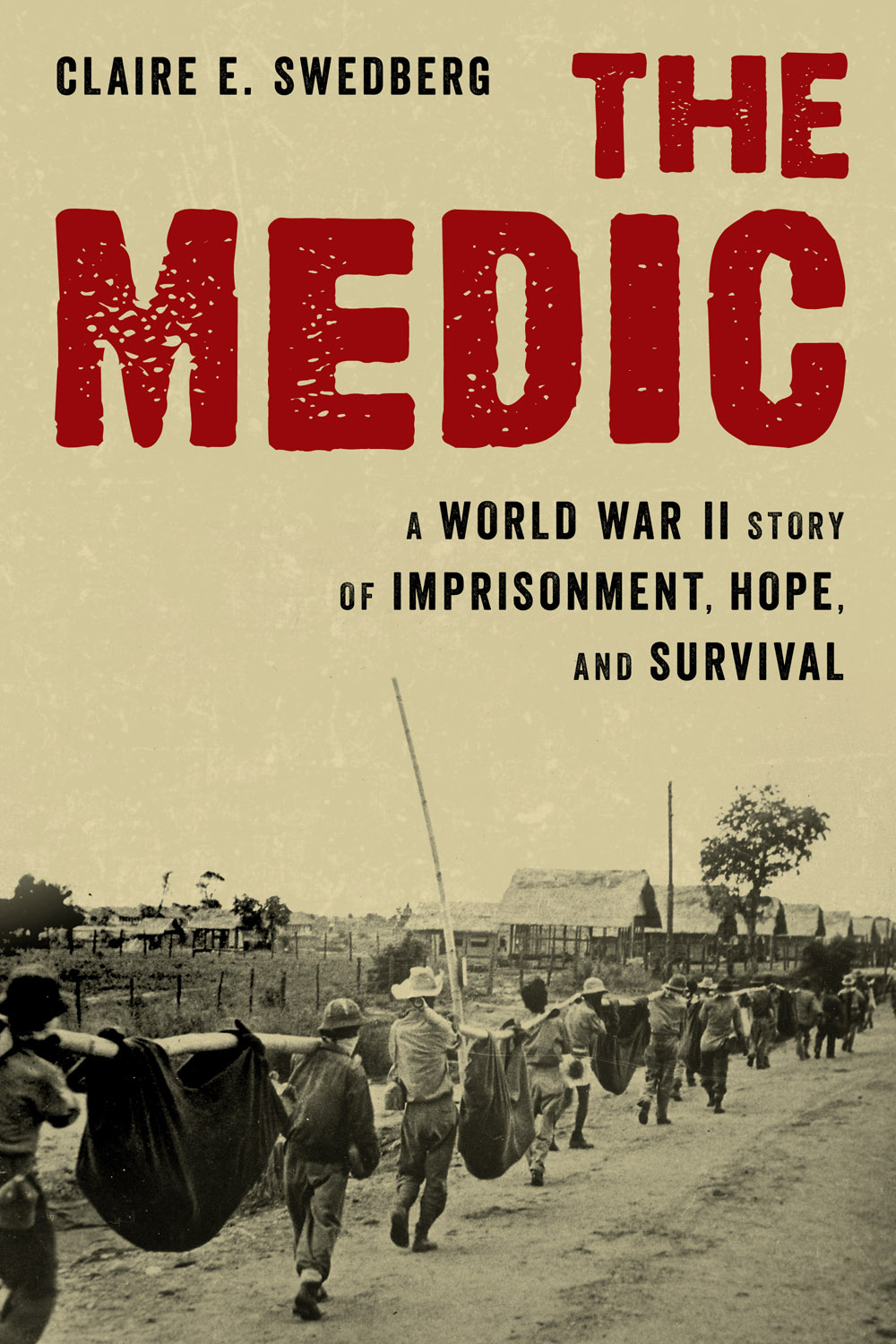

Title: The medic : a World War II story of imprisonment, hope, and survival / Claire E. Swedberg.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Stackpole Books, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: From the Bataan Death March to Japanese prison camp to a hell ship and forced labor, American medic Henry Chamberlain survived the horrors of three and a half years of imprisonment during WW II. Claire Swedberg tells his story of excruciating hardship, abiding endurance, and transcendent courage beautifully, with great style and deep pathos Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020057891 (print) | LCCN 2020057892 (ebook) | ISBN 9780811739955 (cloth) | ISBN 9780811769839 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Chamberlain, Henry Tilden, 1922- | World War, 1939-1945 Prisoners and prisons, Japanese. | Prisoners of warPhilippinesBiography. | Prisoners of warUnited StatesBiography. | World War, 1939-1945 Concentration campsPhilippines. | World War, 1939-1945Medical care Philippines. World War, 1939-1945Concentration campsJapan. | World War, 1939-1945Medical careJapan. | Bataan Death March, Philippines, 1942. | United States. ArmyMedical personneBiography.

Classification: LCC D805.P6 S94 2021 (print) | LCC D805.P6 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/7252092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057891

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057892

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

I dedicate my story to those former American prisoners of war who gave their lives to protect their families, friends, and our country.

Henry T. Chamberlain, Staff Sergeant, USAF (ret.)

CONTENTS

Guide

T his story is based on the life and recollections of World War II US Army Medic and surgical technician, Henry T. Chamberlain. The events here are true and based on his personal accounts, as well as corroborative research. Several names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals families.

A project such as this relies on the support of innumerable, international researchers, historians, authors, and witnesses to these events. Throughout the entire process of collecting and writing Henry Chamberlains stories, I was assisted by a knowledgeable team of historians from Japan, the Philippines, and the United States who supported the writing process by providing context, background, and fact-checking. Im especially grateful to all the POWs and veterans who published or otherwise shared their stories. Each individuals experience is both personal and universal and Im grateful for every story I had access to. Special appreciation must be mentioned to historians Desiree Benipayo, Cecilia Gaerlan, James Zobel, The MacArthur Museum, Bob Hudson, Mine Takada, Sanders W. Marble, and the US Army Medical Department Museum. Thanks go to the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor and its dedicated members and officers for keeping history alive. Thanks to Joe Brown who shared the story of his father Charles Brown, a POW of Cabanatuan. My gratitude also goes to the Chamberlain family, all of whom supported Hank in retelling his story and ensured we had space, time, and support to carry on our unending conversations. Editorial and personal support came from my family and most especially my husband, Michael Wirth.

Finally, I thank Henry Chamberlain for having the gracious generosity to tell his story without hesitation and without filters. He proved throughout this process to have patience, humility, and patriotism. Through telling his story I have learned that he has lived his life and especially his war years with bravery, selflessness, and nobility. I am no hero, he often declared. Ultimately, I leave it to the readers to make their own conclusions. I hope those who read this story gain an appreciation for this history, find the spirit of survival embraced by these POWs, and can share Hanks goal that nothing such as this ever happens again.

2017, SENDAI, JAPAN

S eventy-five years had passed since Henry Chamberlain last laid his eyes on the mine god that presided over the shaft of the Mitsubishi lead and zinc mine. The contrast between that timeWorld War IIand today couldnt have been more striking. Now, as a ninety-six-year-old, he rested between the support of his daughter on his right and his Japanese interpreter on his left. The rain fell softly on the small huddle of dignitaries around himMitsubishi executives, as well as a group of historians and diplomats, none born yet when hed left this place. One member of the delegation raised a wide umbrella over Chamberlains head.

The former POW gazed at the empty frame that had once contained a shiny, towering Japanese deity, guarding the entrance, installed to ensure good fortune for the mine and the men working inside. Chamberlain had cursed that symbol, day after day.

What are you remembering? his guide asked through an interpreter. He pointed.

We had to bow to a figure there, his voice was calm and steady, no anger left in him. Every day we bowed on our way in, and then we turned and bowed again on our way out, he said. The interpreter repeated his words in Japanese. The group listened with sober expressions, a few nodding their heads. Chamberlain was staggered by the contrast between his considerate hosts and the barbarism of his past. So he told them the rest, the part he hadnt mentioned for decades: about the last time he had seen the figure, on liberation day. He described the way he glared at that silent figure consumed with rage of the past wars injustice. At that time, in 1945, he had lifted his middle finger high over his head I shouted, F-you! his eyes shone with the memory of that triumph. This too was interpreted to his hosts, and no flash of anger, no objections arose. This was history now.

The mine was now in disuse but tidy, silent, while the mountainous landscape loomed around, lush in its greenery. But memories clamored around Hank. He could feel, he could see, the presence of several hundred men, all dead now, but standing there beside him, some Americans, some British, in various stages of starvation and sickness, all faces raised to the god.

Those prisoners spirits around him were dressed in the ragged remains of what had once been starched Army uniforms, now just a few scraps knotted around their waists to cover their privates. Some wore clogs theyd hammered out of discarded chunks of wood, others stood on their bare, calloused, or bleeding feet. Their hollow eyes seemed to consider another twelve hours in an endless litany of long days labor underground. Chamberlain, the only medic working the mine, was there to help those who collapsed, if they were still alive.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.