This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1943 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

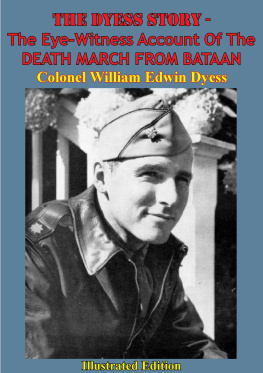

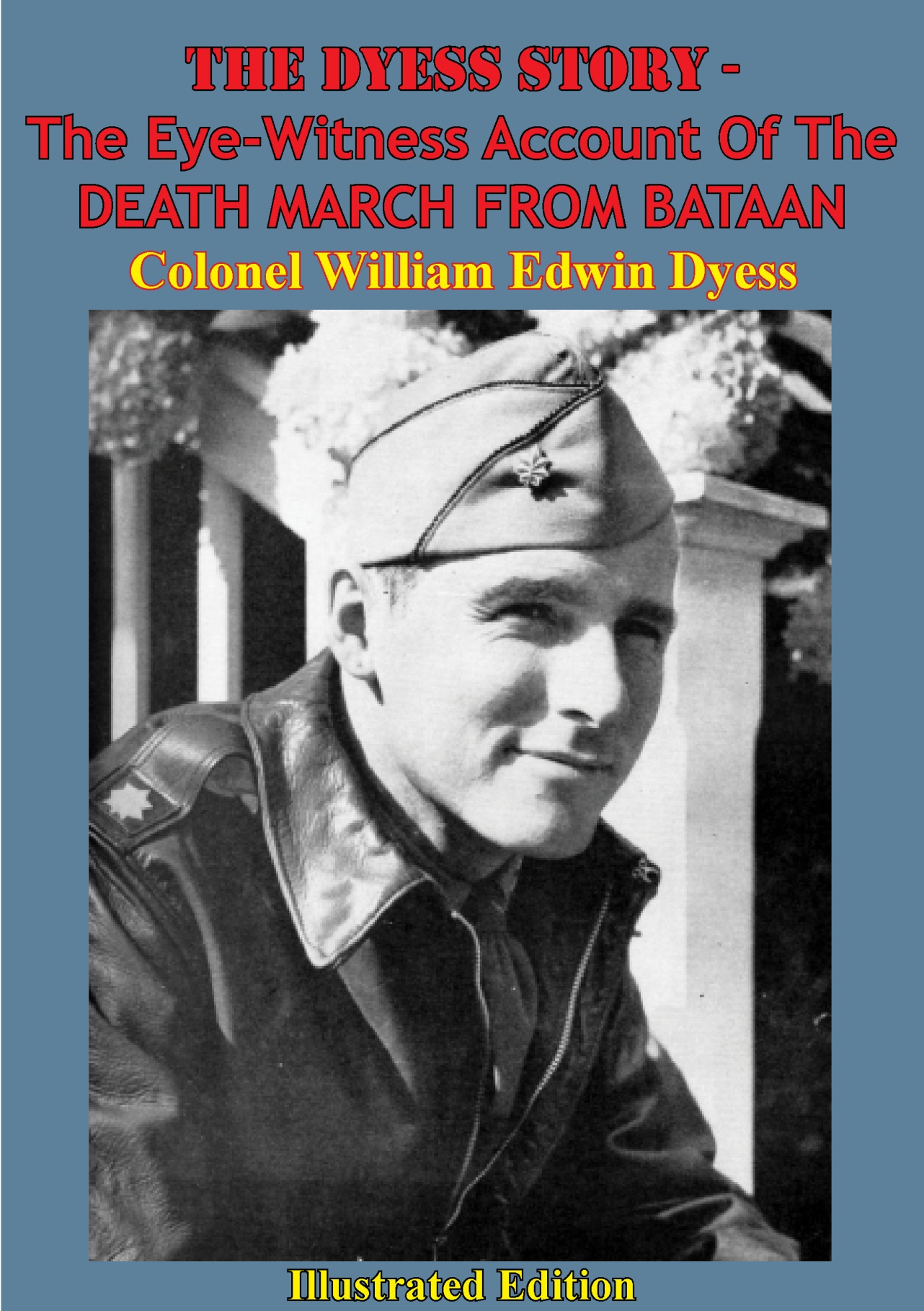

The Dyess Story

The Eye-Witness Account of the DEATH MARCH FROM BATAAN

and the Narrative of Experiences in Japanese Prison Camps

and of Eventual Escape

BY

LT. COL. WM. E.J. DYESS

Edited, with a biographical introduction, by CHARLES LEAVELLE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

TO THE AMERICAN HEROES OF THE PHILIPPINES LIVING AND DEADAND THEIR GALLANT FILIPINO COMRADES, THIS BOOK. IS HUMBLY DEDICATED.

FOREWORD

This book is based upon a series of stories first published by The Chicago Tribune, whose kindness in permitting their reproduction here is gratefully acknowledged, and special thanks should be given to Melvin H. Wagner of the Tribune, who drew the maps, and to Swain Scalf, also of the Tribune, who took, both at White Sulphur Springs and Champaign, the photographs here reproduced which are not otherwise credited.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Lieutenant Colonel William Edwin Dyess Officers Mess at Bataan Field Dyess Celebrates Raid

Captain Dyess after His Bombing Raid in Subic Bay A Shelter near Bataan Field

Major General King and His Staff after Capture by the Japanese

Prisoners Being Disarmed by the Japanese at Mariveles

Articles Carried on Death March

Dyess Trophy: A Moro Kris

The Dyess Diary

Captain Samuel C. Grashio

A Message from the Prison Camp

General MacArthur Greets Escaped Heroes

Dyesss Cablegram Announcing Escape

The Prison Food

How He Downed a Jap Fighter

Col. Dyess in Hospital

Dyess Relates His Experiences

In the Summer of 1943

At White Sulphur Springs

INTRODUCTION

In the humid heat of an Australian field hospital on a day in July, 1942, the late Byron Damton of The New York Times was talking to Lieutenant (now Major) Ben S. Brown, fighter pilot of the United States Army Air Forces. Brown, awaiting a minor operation, had been one of the last American officers to be evacuated from the Philippines before the fell of Bataan.

I didnt want you to come to see me so I could talk about myself, Brown was saying. I want to tell you about Captain Ed Dyess. I dont think his story has been told back in the United States and I think it ought to be. Ed is a Texas boy, over six feet tall. He was twenty-six years old this month. Boy! Was he the ideal officer!

Brown talked on and Damton took notes, though the story already was more than three months old. The dispatch he sent was printed throughout the country, then it was clipped out and buried with a million other items in newspaper morgues. Damton was killed three months later in an airplane crash somewhere in New Guinea.

But the stage had been set for one of the most dramatic news breaks of the war. Nineteen months later, in January, 1944, the Dyess story burst upon a shocked nation. It was acclaimed by statesmen, clergymen, editors, and the American people as an historic document which would figure decisively in the shaping of peace terms for Japan; one whose full significance could be measured by time alone.

The story of Dyess and his companions and the atrocities they had witnessed had been withheld for months by the government in the fear that its publication would result in death to thousands of American prisoners still in Japanese hands. When all hope of aiding the prisoners passed, the story was released.

The swift recognition of the Dyess storys importance is due largely to Byron Damtons dispatch, which might never have been written, except that World War II has been the most fully reported conflict in history. The army of newspaper and magazine correspondents and photographers is the greatest ever assigned to a war. Their intensive coverage of even the most remote sectors on the battlefronts of the world has unearthed and preserved thrilling and historical chapters by the thousands. It was this new standard of war reporting that took Damton to the isolated Australian hospital where he met Ben Brown.

It was a year later, in July, 1943, that a brief telegraphic dispatch chronicled the safety and good health of one Major William Edwin Dyess, of the army air forces, who for many months had been a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese army. In some newspapers the dispatch appeared as written. In many others it did not appear. Certain-editors sent the dispatch to their morgues with the scribbled query: Who is he? And when the Damton clipping was laid before them, the Dyess item became big news.

Ed was the commanding officer of the field squadron, the Times correspondent had written in the words of Lieutenant Brown. Ed had a lot of work to do, but nine times out of ten when a dangerous mission came up he would take it. There wasnt anything the pilots wouldnt do for Ed, because he never asked them to do what he wouldnt do.

We got word one day that three 12,000-ton tankers and transports, a cruiser, and some destroyers had pulled into Subic bay on the western coast of Luzon island. Ed took a P-40, hung a 500-pound bomb onto its belly, and started out to bomb and strafe the Japs. He made three trips. I was his relief pilot, but he wouldnt let me fly. He did it all himself.

He missed the ships with this bomb but hit a small island on which supplies were stored and blew them up. By strafing, he blew up one 12,000-ton ship, beached another, and sank two 100-ton launches. And he strafed troops and docks and caused a lot of casualties.

Next day the Japanese radio reported that Subic bay had been attacked by a big force of four-engined bombers and forty or fifty fighters. I tell you that to give you an idea of the sort of guy Ed is.

The time came when we had to get out of Bataan. We had only a few planes left and the jig was up. Ed gave orders for all of his pilots to leave. But he refused to go himself.

There were 175 men and 25 officers who could not possibly get away because there was nothing to take them away in. And Ed wouldn't go unless they could. I tried to get him to, but he wouldnt.

Dyesss importance as an American heroas established by Damtons dispatchwas responsible for a concerted rush to obtain the full story. And when, in the course of their efforts, newspapers and magazine editors learned something of Dyesss appalling experiences in Japanese prison camps, the struggle for the right to publish them grew epochal.

By September 5, 1943, when Dyess was recuperating in the armys Ashford General Hospital at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, the stiffening competition had narrowed the field of bidders to a national weekly magazine and The Chicago Tribune , representing 100 associated newspapers. The Tribune was successful, not because it outbid the magazine, but because it could promise Dyess, now a lieutenant colonel, a daily circulation of ten million and an estimated daily audience of forty million against the magazines circulation of about three million weekly and estimated reader audience of twelve million. Colonel Dyesss consuming determination to expose to the world Japans barbaric treatment of American war prisoners decided him in favor of the daily newspapers and their vastly larger audience.

Next page