The books in this series portray and analyze the experience of Americans in military service during war and peacetime from the onset of the twentieth century to the present. The series emphasizes the profound impact wars have had on nearly every aspect of recent American history and considers the significant effects of modern conflict on combatants and noncombatants alike. Titles in the series include accounts of battles, campaigns, and wars; unit histories; biographical and autobiographical narratives; investigations of technology and warfare; studies of the social and economic consequences of war; and in general, the best recent scholarship on Americans in the modern armed forces. The books in the series are written and designed for a diverse audience that encompasses nonspecialists as well as expert readers.

Editors Preface

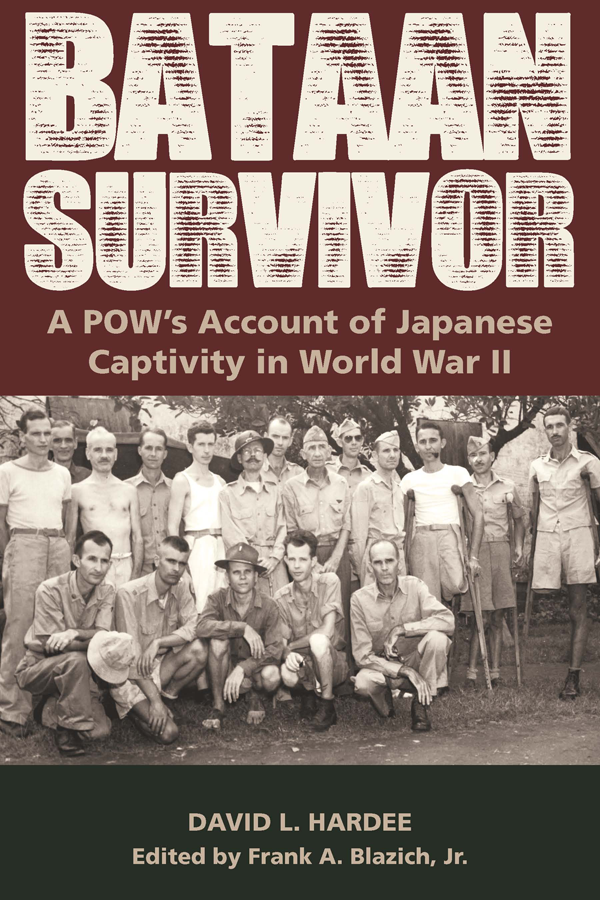

In many respects, this current work is only available due to a series of coincidences and instances of good fortune, not the least of which being Colonel Hardees survival. I stumbled on his memoir in the course of my doctoral studies. While researching the civil defense history of North Carolina in the fall of 2009, I happened upon a small item in the NovemberDecember 1969 North Carolina Civil Defense Agency newsletter, mentioning the passing of the colonel. Two sentences about Hardees life caught my eye: His distinguished military career lasted from World War I to 1949, when he retired with twenty decorations, including the Distinguished Service Cross and Bronze Star. He was a survivor of the Battle of Bataan, the infamous Death March and three years as a prisoner of war.

Thus began my journey back to the dark days of World War II. After an initial internet query proved disappointing, a reference in the footnotes of Duane Heisingers Father Found pointed to a copy of the Hardee memoir located at the U.S. Military Academy Library. Out of sheer curiosity, I hunted through the collections of the various state and university libraries in North Carolina, but I could not turn up a copy of the memoir. It was through working with two fellow graduate students, Geoff Earnhart and Will Waddell, that I finally got my hands on Hardees text. Geoff obtained the memoir for me to transcribe, and Will proofed my typing.

Locating Hardees family initially proved challenging. After finding Hardees 1969 obituary on microfilm archives, I located his son-in-law, Dr. Lee Remmers, who had married Hardees eldest daughter, Elizabeth, at INSEAD graduate business school in Fontainebleau, France. I emailed Dr. Remmers on April 9, 2012, coincidentally, the seventieth anniversary of Bataans surrender.In his reply, he acknowledged awareness of the manuscript but noted the amount of editing required had thwarted previous publishing attempts. Elizabeth Frances Hardee Remmers had passed away in 1979, but Dr. Remmers put me in touch with his late wifes sister, Mary Hardee Stutz.

From my first phone call in April 2012 to the present, I have had the greatest pleasure in working with Miss Mary to bring her fathers story to press. My first visit in June 2012 was an absolute treat as we spoke at length about her fathers service. With her permission, I drove home that evening transporting the personal papers and artifacts her father had carried throughout the war in the Philippines and oversaw their donation to the State Archives of North Carolina and the North Carolina Museum of History, respectively. Through a contact in the U.S. Army Awards and Decorations Branch, I assisted Miss Mary in submitting paperwork for a review of her fathers military service record. This effort resulted in his retroactively receiving the Prisoner of War Medal, a second Purple Heart for gas exposure in World War I, and other additions to his service decorations. Tragically, Miss Mary passed away on October 11, 2016 while the memoir was being typeset, but she went to the Lord knowing her father's story would be told at last.

In presenting this memoir, every effort has been made to retain Hardees original text and structure. Using a blend of primary and secondary sourcesespecially other prisoner memoirsI have attempted to provide for Hardees story a thorough contextual underpinning. I intentionally placed an emphasis on using published memoirs and other scholarly works to make this story as accessible as possible to both general readers and scholars.

As is often the case with an early draft, names and geographical locations were frequently misspelled in the original manuscript, and where I could confirm the appropriate names, these have been amended. In the interest of consistency, terminology and abbreviations have been standardized throughout the text. Other vestiges of the memoirs origins as a seemingly spoken text, such as paragraphs composed of one or two sentences or idiosyncratic punctuation or spelling, have given way to complete paragraphs and regularized punctuation and spelling. In rare instances, subtle editing has provided clarity for inexplicable word choice or sentence structure. Fortunately, little of Hardees writing required modification.

Readers may take issue with the decision to retain the period language, notably Hardees references to the Japanese as Japs. Hardees animosity and racist descriptions of his captors are the products of his experiences during theconflict, and he rarely shares such attitudes toward Filipinos or other cultures in his writing; therefore, I have chosen to leave them as written by Hardee.

Hardees story would not now be in the light of day without the time, energy, and support of countless people. I wish to express my gratitude to my former colleagues at the Ohio State UniversityMajor Geoff Earnhart, for obtaining a copy of the memoir from West Points library, and Dr. William Waddell, for assisting in the location of source material, proofing the manuscript, and assisting in the editing process. Without their work and good counsel, this project would never have advanced beyond an internet search.

In addition, no book comes together without the assistance of the family. From the Hardee family, I wish to thank Dr. Lee Remmers for sharing memories of his father-in-law. Most of all, I am indebted to Mrs. Mary Hardee Stutz, who opened up her home and warmly welcomed me, generously giving her time to provide invaluable insight into her father and clarification of facts about points in his life.

My own family has supported me throughout this project. My older sister, Joan, assisted with editing oversight on the text and notes, and my brother-in-law, Brian, always had a good word when I hit a wall. My father died unexpectedly before this books publication. A keen historian in his own right, he took a great interest in Hardees story and made editorial suggestions after reviewing the manuscript. My mother listened to my research quandaries, supported trips to the archives, and could always be depended upon for an encouraging hug and a supportive chat.

In the course of my work, I crossed paths with a number of archivists, historians, researchers, colleagues, and friends who have all contributed to the final product. Dr. Robert Doyle, Mr. Kenrick Simpson, Dr. Joe Porter, Dr. John McManus, Ms. Sara Davis, Mr. Clair Willcox, Ms. Diann Benti, Ms. Kim Andersen, Mr. Phil Zubiate, Mrs. Mary P. Johnson, and Mr. Wesley Injerd helped with research, literary, or technical questions. To the friends from graduate school and federal service with whom I have shared this memoir I express my deepest appreciation for keeping my spirits up and faith strong. Notably, a gracious thank-you to Dr. James Bartholomew, the late Dr. John Joe Guilmartin, Dr. Peter Mansoor, Mr. Zack Fry, Major Shauna Hann, Mr. Tom Reilly, and Mrs. Sharon Reilly. Finally, a hearty salute to Colonel Hardee for saving his part of the past, thus granting me the privilege of sharing his story with you.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper