Contents

About the Author

Michael Simkins is a familiar face on the west end stage and TV screens, usually playing experts, policemen or unsuspecting husbands. Most recently hes played Billy Flynn in Chicago and the Pierce Brosnan role in Mamma Mia (or as hed rather think of it, the Michael Simkins role which Pierce Brosnan subsequently played in the film). Countless TV and film appearances include Foyles War, Minder, Lewis, and Doctors as well as turns on the silver screen in such films as Mike Leighs Topsy-Turvy and V for Vendetta. He is a frequent contributor to Radio 4 and writes for the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian and The Times.

His first book Whats My Motivation? was Radio 4 Book of the Week and his second, the critically acclaimed Fatty Batter, was shortlisted for the 2008 Costa Biography Award.

Michael lives with his actress wife Julia in London.

Michaels website can be found at: http://authorsplace.co.uk/michael-simkins/

About the Book

Michael Simkins has a nagging feeling helpfully upheld by his partner Julia that he somehow lacks worldly sophistication. Hitting middle age, he is beginning to suspect that between county cricket and his M&S weekend casuals he may have missed something.

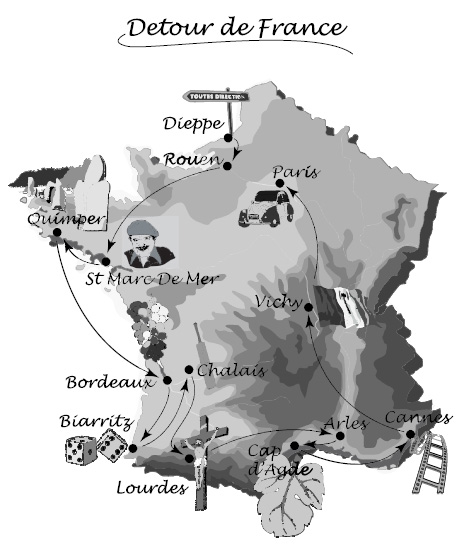

Shaking off the shackles of middle England, Michael takes up the challenge of broadening his horizons. Armed with almost four words of French he sets off on a slightly ill-conceived trip round La Belle France, hoping to pick up a soupon of their god-given cultural refinement along the way.

For Julia

Son et Lumire

MY RELATIONSHIP WITH France began when I was interfered with at the cinema.

It occurred at my local fleapit in Brighton during the summer holidays. I cant have been more than nine or ten at the time. I cant even recall the main feature, but the second film in the programme was a curious French movie with English subtitles I hadnt bargained for: Monsieur Hulots Holiday.

Set in a fictional seaside resort on Frances Atlantic coast, this strange and beguiling comedy depicted the gently anarchic adventures of French comedian Jacques Tatis alter ego during one summer in the 1950s.

The real star of the film was the location itself: a small, sleepy resort, complete with sun, sea, sand, donkeys, laughing children and evening strolls along the prom. It could almost have been Brighton, if it werent for the fact that it was hot, elegant, exotic, timeless, languid, and everyone in it spoke as if theyd bitten on a glue trap.

Midway through the picture, the cinemas only other occupant, a man in his forties with greasy hair whod been sitting a few rows in front, squeezed between the seats, plonked himself down next to me and moved his right hand onto my left knee.

By the time hed manoeuvred it onto the zip of my shorts (just as Hulot commenced his famous game of ping-pong in the hotel lobby), I knew something was wrong. Yet, despite all my parents dire warnings, so entranced had I become by the strange sunlit world that I couldnt bring myself to leave. I merely moved my seat and crossed my legs.

That had been my relationship with la belle France ever since. Fascination mixed with mild anxiety. Even now I can never talk to a Frenchman without feeling Im being molested.

Dj View

EVER SINCE KING Harold sent his army careering after William the Conqueror with the proviso, Mind where you shoot those arrows, you could have somebodys eye out, Englands relationship with that of our nearest neighbour has been all downhill.

Youd have thought that losing a kingdom but gaining a conqueror would have settled the issue: wed take their foie gras, theyd take our fried bread, and wed be one big happy family. But bad blood lingers and ever since 1066 weve been at each others throats. From the Hundred Years War to Waterloo, from the European Union to the Eurovision Song Contest, weve remained the best of enemies.

The French see themselves as natures aristocrat. In cuisine, manners, the arts, fine wines, philosophy and, as if all that wasnt galling enough, now even in football, theyve appropriated the mantle of true class, while England is fighting relegation, both sporting and cultural, in the Beazer Homes League Division II. The French ideal is represented by a piquant blend of Juliette Binoche, Coco Chanel and Arsne Wenger. Fighting for all that we hold dear in the English corner would be Ann Widdecombe, John McCririck and Mister Blobby.

The problem is how we choose to see each other. While we may have beaten them in the run-off to host the 2012 Olympics, Boris Johnsons flag-waving at the closing ceremony in Beijing confirmed everything for which the Brits are known on the boulevards of Paris knock-kneed, pasty, overweight and sartorially about as well turned out as the Mayor of Londons splayed feet.

We, on the other hand, see them as proud, stuck-up, rude, impatient, humourless and bombastic.

They see themselves the same way, of course, but to them these are the things that make life worth living.

MY OWN VIEW of the French, I have to confess, was still stuck in the back row of that cinema and weighed down with years of caricature. I grew up knowing little more than that wed helped them out in two world wars. Whenever France was mentioned in our house, my dad would stare darkly into his tea cup and murmur grimly, Nobody ever forgives you for doing them favours. My elder brother Pete during his college years was briefly part of something called the Reconquer France for Britain Society, although that turned out to be an excuse to go on day trips to Dieppe and get bladdered. Yet the prevailing antipathy chez Simkins towards all things French was at odds with my own flickering, Hulot-kissed memories.

Sadly, I never had a chance to decide for myself. I didnt have a French pen friend, I never went on a student exchange or skiing holiday, and I failed utterly to learn the language. Not that I didnt have the chance. Au contraire: I spent four years studying French at secondary school, but there were just too many other things to do in the back row of the classroom sticking compasses into Lumper Lawrences right thigh or perfecting my Johnny Mathis impression to mention just two.

When I was allowed to give it up aged sixteen I had little more knowledge than the opening lines of Frre Jacques, and thats the way it stayed. I went straight from secondary school to drama school and to my first paid acting work, and the smell of garlic was no match for greasepaint. My wanderlust years slipped by without my noticing. Even into my twenties, my idea of a fabulous trip to foreign climes was playing Wishee Washee in Aladdin.

So the gap between the France of my imagination dreamy, poetic and liltingly beautiful and the image commonly depicted in English culture aloof, snobbish, with a yard brush up their communal derrire remained as wide as the Channel. I could whistle the theme tune from Maigret, but that apart, the strange, sunlit world Id glimpsed all those years ago in the darkness of a provincial cinema remained a distant fantasy. Yet somewhere inside me I still dreamt occasionally about one day finding the France of Hulot.

Next page