Contents

Both lands had once been part of the same. There was sand and rock still fresh from the stars, and a salt desert which writhed and folded and threw fire into the sky. And the desert formed a basin, and beyond the basin to the west was a raging ocean which burst through in a mighty waterfall and poured an entire ocean into the space it found. Then explorers crossed the water, followed by armies. There were battles fought and great ships lost, and conquerors crowned as kings. And the men of the north took all that was good from the land across the sea, all that was laced into the earth, or ripening beneath the hot sun. And when they returned to the north, with all that they could carry, some of those from whom theyd taken decided to follow...

About the Book

Eighty miles off the North African coast, a tiny fibreglass boat is sinking. There are twenty-seven men crammed on-board are desperately trying to bail it out, but the weather is closing in. Then one of them spots a ship on the horizon. They change course and head for their only hope of survival. But when they arrive, theres an unexpected reception.

The men end up stranded on the the floats of a giant fishing net as their boat finally rolls over and disappears beneath the Mediterranean Sea.

Justice Amin, is exhausted, cold and soaked, but at least he has something to cling onto.

As night comes, all hopes of rescue fade and he is left drifting in a hazy place between Africa and Europe, darkness and light, innocence and experience.

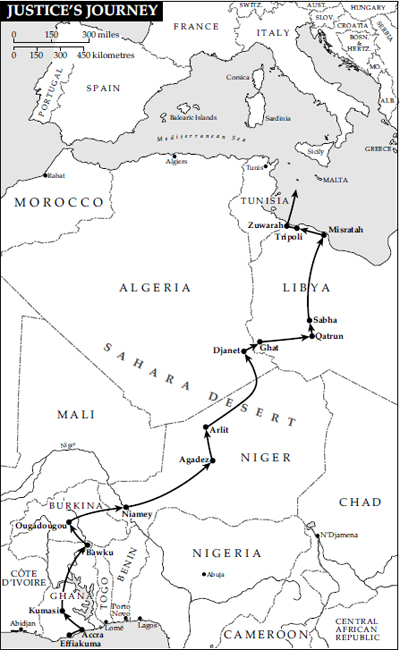

Justices journey began in Ghana, at the hands of his uncle, an abusive medicine man. Determined to make something of his life, he fled across the Sahara Desert, before being captured, jailed and tortured. He managed to escape and headed for the people smugglers of Libya, who he hoped would sail him to freedom and prosperity across the sea to Britain, the home country.

I Am Justice

A Journey Out of Africa

Paul Kenyon

About the Author

Paul Kenyon is an award-winning journalist who has worked for the BBC for almost twenty years. He is currently a reporter for Panorama, and it was whilst making a two-part documentary on African migrants in 2007 that he became friends with Justice Amin.

Chapter One

JUSTICE AMIN HEARD his uncle patting on the goatskin dondo drum. He could taste the boiled tree bark, as the smell drifted in from the cauldron. Today uncle must have customers, he said to Issah, lying beside him on the mat. I will leave before he starts.

He pulled a pair of trousers from a nail on the wall and waited behind the door. On the other side was a dark, windowless porch. It was hammered from planks of wood, which were weathered and broken and patched together so unevenly that the whole structure leaned. In one corner was a piece of board, on top of which sat a clay head. It was smooth and hairless, its mouth and eyes roughly carved with a stick. Down its sides dripped a thick black crust. This was where his uncle carried out the sacrifices.

The hut looked out onto a main road where buses and lorries rumbled through on their way to Accra, five hours drive east. They didnt bother stopping in the small community of Effiakuma. The fresh tarmac with its clean white lines and straight borders was the most orderly, well-designed feature in town. The only other roads were dust tracks, lined with abandoned mountains of cement and gravel, and pitted with holes so large they could swallow a car.

On either side of the road were sloping tin roofs which stretched away to the forest. They were corrugated, bronzed by monsoon, and covered in large boulders which had been carefully positioned to stop them flying off in the wind. The buildings were mostly breeze block smeared with cement. The older ones were made from wood. Some were painted with bright murals, advertising Coca-Cola or Anchor butter. Reach for Greatness read one, and then underneath in black letters, Guinness.

Many of the roadside properties doubled as shops: Ninas wigs, Mabes flour, Madam Odobus herbal centre. Inside there was usually a single windowless room with the wares spread out on the floor. One, called Johns Honourable Venture, was a bare wooden hut which opened directly onto the main road. Inside John sat at a small table, a typewriter in front of him, composing letters for the illiterate of Effiakuma.

Passing beneath the road, and weaving its way between the shacks, was an open sewer. It was deeper than a child and too wide to leap. Narrow wooden planks bridged the gap, allowing residents to pass across in single file. Along its middle ran a continuous stream of liquids. To each side lay discarded clothes, plastic bags and bottles around which the solids gathered and baked in the sun.

Justices hut was sandwiched between the main road and the communal washhouse. He lived with his uncle Ibrahim, his brother Issah who was three years his junior, and Zuleyha his baby sister. Beyond the leaning porch was a single room, where they ate, slept, and carried out any job their uncle demanded. The floor was clay, smoothed by years of bare feet, the walls grey brick. The only furniture was a wooden chair, a knee-high table, and a single bed. The children slept on mats. The bed was for the uncle.

Justice had lived with his uncle Ibrahim since he was five, maybe six years old. He wasnt sure. He never spoke of what went before, of his parents or what had happened. Neither did his uncle. The neighbours knew only that Justices father had been a devout Muslim who studied the Koran and sometimes preached, and that he had lived with Justices mother in the orange city of Agadez, on the edge of the Sahara in Niger. That was all. One day the three children arrived on a bus, with nothing more than a bag of clothes. They had lived with their uncle Ibrahim ever since.

For the first few years, there appeared to be harmony, despite the cramped conditions. It was when Justice reached his teenage years that the relationship with his uncle soured. Neither can finish a sentence without making the other one shout, the neighbours would say. Maybe the boys discovered the nature of his uncles business.

Separating the living area from the porch was a heavy wooden door. Its surface was covered in words. Some were scrawled wild and tall, with flourishes of white chalk, others were small and tidy, and curved down the edge of the frame to finish the thought. One read, The evil that man does lives after him.

The drumming stopped. Justice heard Uncle Ibrahim tap a stick on the side of the cauldron, take a knife from the porch, and set off towards the forest. Then he slipped out, past the mosque and the lotto booth, pausing to queue at the thin wooden plank across the sewer which was livid with flies. The path narrowed. Goats rummaged and women kneaded clothes in giant tubs. He raced down an alleyway, geese and chickens flying from under his feet, past the smouldering rubbish tip, out onto the other side, and finally into a quieter area where there was a church tower made from slatted wood. Beneath it, on the other side of a sandy square was the Reverend Grant Methodist School.

Little strong man, a voice shouted from the balcony. Why do your legs move so quickly around a football, but turn to stone on the way to school?

Justice slowed and walked the last few metres across the sand, taking care to show he was in no hurry. The school occupied the first floor of a narrow brick building, four classrooms long, and one deep. There was no glass in the windows, just slatted wooden shutters, which spent much of the year wide open so any movement of air could pass straight through. Most of the time, the rooms were still and humid, and smelt of damp clothes.

Next page