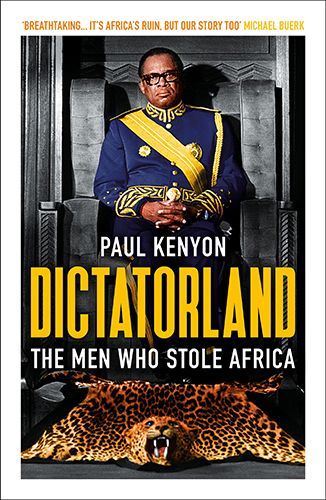

DICTATORLAND

The Men Who Stole Africa

Paul Kenyon

www.headofzeus.com

A vivid, heartbreaking portrait of the fate that so many African countries suffered after independence.

The dictator who grew so rich on his countrys cocoa crop that he built a thirty-five-storey-high basilica in the jungles of the Ivory Coast. The austere, incorruptible leader who has shut Eritrea off from the world in a permanent state of war. In Equatorial Guinea, the paranoid despot who thought Hitler was the saviour of Africa and waged a relentless campaign of terror against his own people. The Libyan army officer who authored a new work of political philosophy, The Green Book, and lived in a tent with a harem of female soldiers, running his country like a mafia family business.

And behind these almost incredible stories of fantastic violence and excess lie the dark secrets of Western greed and complicity, the insatiable taste for chocolate, oil, diamonds and gold that has encouraged dictators to rule with an iron hand, siphoning off their share of the action into mansions in Paris and banks in Zurich and keeping their people in dire poverty.

Contents

To my mother and father, Betty and Neville, who have always encouraged me to be inquisitive, to question authority, and to give a voice to those who do not have one

Also in memory of my father-in-law, Gheorghe, who spent most of his life living under the tyranny of a dictatorship

I T SEEMED A hopeless place to search for human remains, a wilderness of volcanic rock and ancient river sediment on a scorched hillside in East Africa. Everything was lunar grey, not a blade of green, not a glint of water, just the rubble of an ancient planet. Chalachew Seyoum clambered up a slope of slippery scree and found a desolate, windless plateau. It was a January morning in 2013, and he was with a team from Arizona State University, revisiting his Ethiopian homeland for an anthropological dig. Nothing had been found on these remote slopes for more than a decade, but when Seyoum looked down at the bleached stones around his feet, he noticed something out of place.

Jutting from the ground was a small fragment of something smooth and pumice-grey that seemed organic in origin. When he bent down to examine it properly, taking care not to disturb the stones on either side, he saw that it was about eight centimetres in length, a narrow bone-like fragment that was shaped like a beckoning finger. Seyoum lowered his head to the ground, and noticed several protrusions along its length, each about the size of a river pearl, grey, and worn flat on their exposed side. He knew immediately what he had found, although he didnt yet know the age of it.

This was the lower left side of a human mandible with five teeth still attached. Seyoum began shouting for his colleagues.

A man had once sat where Seyoum sat, surveying vast open grasslands where zebras and giant pigs grazed. He may have been up there hunting, when the hillsides were lush green and streams ran along the valley bottoms, before the wild swings in climate and the clashing of the earths plates plunged the region into a barren wilderness. This was an era before man knew how to fashion spears from the branches of a Curtisia tree. Instead they hid in the tall grass, and ambushed their prey with rocks and clubs. If that failed, they would search the caves for remains of a kill by leopards or lions. The meat they scavenged would have been eaten raw. Man still hadnt learned to control fire.

The fragment of mandible represents the burst of evolution that gave rise to humankind 2.8 million years ago, shortly after we had left the forests and stood upright for the first time. Its owner and his tribe were the forefathers of every one of us, chewing raw meat on the gentle, fertile hillsides of East Africa. The rest of the planet was empty of the genus Homo . That fragile stick of bone is the closest we have come to the missing link, the point in time when modern humans split from their more ape-like ancestors. It is 400,000 older than any other found in our lineage. Scientists named it LD 350-1. But we should call him Adam.

When Adams people set off westwards into the scrublands of what is now the Kalahari, and knelt to drink beside a pool of late summer rain, they would have seen sparkling crystals among the sand left in their palms. When they paused at a stream to bathe dust from their rough, chimp-like hair, they would have seen veins of copper-coloured silt, or tiny golden flecks dancing in the currents. The primordial African landscape was full of such wonders: basins of speckled bauxite, pink lakes of trona, canyon walls patterned with livid orange iron ore. Adam might have paused to dip his finger into the glutinous black drips leaking from rock faces near to the coast oil seepages that were already many millions of years in the making.

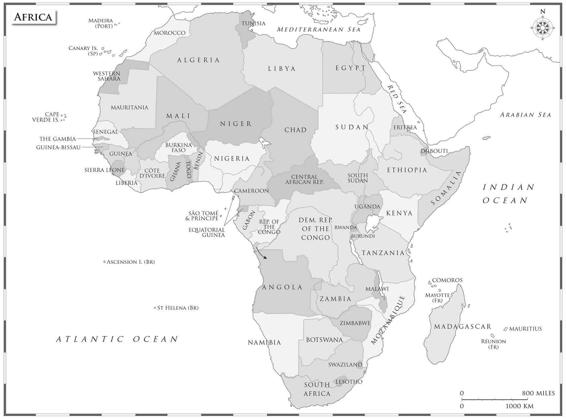

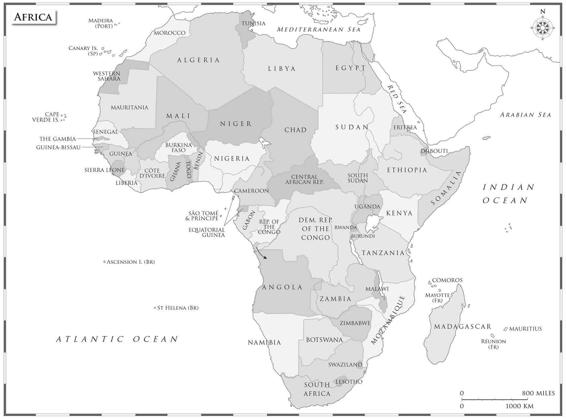

Adam expired on that Ethiopian hillside when he was no more than forty years old, birds of prey circling overhead. It would be several millennia later that his ancestors would undertake the great migration, driven from their land by endless drought and volcanic eruptions, to discover new territories beyond Africas shores. The scattering of mankind to every corner of the earth began relatively recently, just 70,000 years ago. One group crossed what is now the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the pinch-point between East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, sculling across the shallow seas on rafts secured by vines. Others headed north, to milder and more fertile climes. When they found their route blocked by the Mediterranean Sea, they were forced across the Sinai into the Middle East, and then spread into the tropics of central Asia. Others edged closer to the ice, and the snowy wilderness of the north, finally pushing over the top of the world from the East Asian Arctic to the Americas. But wherever mankind travelled and prospered, nothing would match the natural riches that they had left behind in Africa.

By the time Adam was born, the continents wealth was already ancient, mostly created as the earth cooled and a crust formed over its molten rocks about 3.5 billion years ago. Diamonds were forced to the surface when dinosaurs still grazed the grasslands, and when Africa was still attached to the Americas, 150 million years ago. Formed in a furnace of carbon just above the earths mantle, they were blasted to the surface from spectacular diamondiferous volcanoes that hurled them a mile into the Jurassic sky. In the middle of the nineteenth century our most respected geologists would have scoffed at the idea that diamonds were showered over the landscape by explosions deep inside the earth. They believed the gems came from alluvial deposits, dislodged from the earth by ancient rivers, and swept along in the mud and silt. But then came an event that changed all previous scientific thought, and led to a diamond rush like no other.

A group of prospectors known as the Red Caps were passing through a barren, rock-strewn wasteland in southern Africa, just beyond the border of Britains Cape Colony, when they stopped for a half-hearted inspection of the land. It was 1871, and a series of high-profile finds along the banks of the Vaal and the Orange rivers had attracted diggers from around the world. Some became rich with a single, spectacular discovery; most returned home exhausted, disease-ridden and penniless. The Red Caps were on their way to join the hopeful throng, and had no intention of starting a dry dig away from the waters edge. They had stopped for a rest when their leader, Fleetwood Rawstone, sent his cook to the summit of a small hillock, known in Afrikaans as a kopje , as punishment for being drunk the previous night. While up there, in the searing afternoon heat, the cook kicked the dusty soil and felt something hard beneath his boot. It was a large, translucent stone. He shouted for the others to join him, and within hours they had found many more. The hillock was, in fact, the peak of the first diamondiferous volcano ever found, and was sitting on top of a diamond pipe that stretched almost a quarter of a mile down, its contents studded with gems like raisins in a cake. Tens of thousands of prospectors descended on the kopje from Europe and America. Diamond fever gripped the region. The land where the volcano stood was part of a farm owned by two Boer brothers who began renting out plots for excavation. Their name was de Beers.