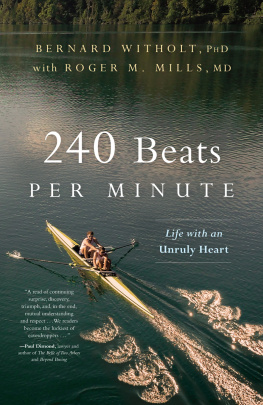

Praise for 240 Beats Per Minute

This absorbing, ambitious blend of memoir, science, and friendship, traces in two voices the journey of Bernard Witholt, an eminent Dutch biologist with a diseased heart and his lifelong friend, cardiologist Roger Mills. Witholt grapplessometimes unconventionallywith years of tachycardia while stubbornly attempting to sustain a vigorous life. One cannot reflect on this compelling account without saying that it has heart in more ways than one. Witholt brings a scientists curiosity into how the heart works to his problems, while Mills interspersed, accessible reflections on his friends journal entries are fascinating, compassionate, and clear. This book is a gift to health care professionals treating heart patients, to patients facing their own conditions, and to readers open to a story about resilience in the face of challenge, about the mechanisms of an unruly heart, about the power of friendship even after death, and about the dignity of a life well-lived.

JAN WORTH-NELSON , Editor, East Village Magazine, poet, author, and lecturer emerita, University of Michigan, Flint

Kudos to Drs. Witholt and Mills for bringing to light one of the most important issues in contemporary medicine: the psychological impact of sophisticated medical treatments. This book is a must-read for those of us who practice high tech medicine and for our patients who spend their (remaining) lives on the cutting edge.

PETER KOWEY, MD, FACC, FAHA, FHRS , Emeritus Chair, Cardiology, Lankenau Heart Institute, William Wikoff Smith Chair, Cardiovascular Research, Lankenau Institute of Medical Research, Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology, Jefferson Medical College

Persons referenced in this book may be composites or entirely fictitious, thus references to any real persons, living or dead, are not implied.

Published by River Grove Books

Austin, TX

www.rivergrovebooks.com

Copyright 2018 Roger Mills and Renske Heddema

All rights reserved.

Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright law. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright holder.

Distributed by River Grove Books

Design and composition by Greenleaf Book Group

Cover design by Greenleaf Book Group

Cover images iStockphoto.com/simonkr

Publishers Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

Print ISBN: 978-1-63299-186-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-63299-187-4

First Edition

Contents

A Note from the Editor

In 1999, my close friend, the Dutch scientist Bernie Witholt, received a device, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), to control ventricular tachycardia, a potentially fatal heart rhythm problem. I had completed my formal training as a cardiologist at Harvards Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1975 and had spent three decades working with seriously ill patients. As I watched Bernie living with his ICD, I realized that no one really understood how patients adjusted to these devices. Cardiologists implanted the devices and said, There, thats fixed. Next.

Bernie quickly realized that his problem was not fixed. With his ICD, he had just traded one very serious problem for a new one (also serious but less likely to be fatal).

Today, almost twenty years later, theres growing medical literature on the quality of life for patients with implanted cardiac devices. A consensus has emerged that depression and anxiety are common problems in patients whove received an ICD. Nonetheless, this literature inevitably reflects a medical viewpoint, not the patients. Bernie was a scientist and teacher; he wanted to share his thoughts about his heart and his ICD with others. He wrote extensively over several years, with every intention of putting his thoughts together into a book. He did not have the opportunity to do that, but his wife has allowed me to edit and arrange what he wrote.

Bernie had a PhD in biology and achieved great success in research and teaching, but when he wrote about circulatory physiology (how the heart works) and, most notably, his speculations on his arrhythmias origin and regulation of body temperature, his ideas did not always follow currently accepted medical understanding. I have made some corrections to his notes, but they are minimal. First, because he was very smart and doctors are not always right, and second, because the critical purpose of this book is to recount how one particular patient dealt with his illness over fifteen years. This is not a physiology text.

I attempted to structure Bernies book as a continuation of a conversation that we carried on over decades. That conversation began at Amherst College, so some background about the college in the 1960s is important. I have also added some technical information and, from time to time, made comments when, based on my thirty years of clinical practice, some particular understanding of the doctorpatient relationship is important.

To make it clear whether you are reading Bernies words or mine, his material will appear in regular font and mine in italics.

Acknowledgments

If I attempt to thank every individual who has played a part in the genesis of this book, the acknowledgments will stretch almost as long as the narrative itself. This section is, by necessity, selective.

Dr. Tom Jacobs, professor of clinical medicine at Columbia and one of Bernies roommates at Hopkins, reviewed my arrangement of Bernies papers.

Dr. Peter Kowey, electrophysiologist and mystery writer, read an early draft of the manuscript, offered his insight, and encouraged me to keep on working. Paul Dimond, lawyer and author, read a later draft, made critically important suggestions, and encouraged me to keep on working, as did Jan Worth-Nelson, lecturer emeritus in creative writing at UM-Flint, and Tom Sullivan, career reader and teacher of English poetry. I thank all of you for your friendship, your criticism, and your support.

My wife, Katherine, cheerfully put up with my hours in front of the computer; Posie, our Labrador, demanded her regular walks and helped to keep me fresh. For the uninterrupted time, and for the interruptions, thank you both.

Finally, I give my heartfelt thanks to Bernies wife, Renske Heddema, for her confidence and trust in sending Bernies writing to me, allowing me a free hand in editing his work, and encouraging me to add my comments.

Roger M. Mills MD, FACP, FACC

Dexter, Michigan

Prologue

Strangers once, we came to dwell together...

Now were bound by ties that cannot sever

All our whole life thro...

Those lines begin the Amherst College Senior Song. In 1960, we freshmen were strangers, each of us unsure of ourselves and the other 282 members of the class. We dwelt together in the freshman dorms, we ate together in Valentine Hall, and we attended classes together. The academic environment catalyzed the bonding process. In the early 1960s, all-male Amherst still followed the New Curriculum of 1947 (8 a.m. classes, Saturday morning classes, required twice weekly chapel attendance, and a required swimming test). Core courses were English 12, History 12, and Physics 12, with no electives except the foreign language of your choice. Very soon, we were no longer strangers. Although we may not have known each others backstories, we knew we were all in it together.

Under the circumstances, it seems odd that I did not get to know Bernie Witholt that first year. He was part of a quiet and studious crowd. In contrast, I studied hard but was drawn to the opportunity to try new athletic and social opportunities. I had never ice-skated but joined the freshman hockey team; I had never seen a lacrosse stick but joined the freshman lacrosse squad. I also had the requisite false ID and classmates who enjoyed pizza and beer at the local bar.

Next page