PRISON JOURNAL

GEORGE CARDINAL PELL

PRISON JOURNAL

Volume 1

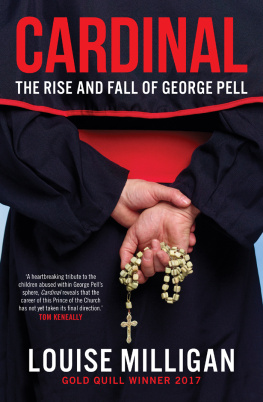

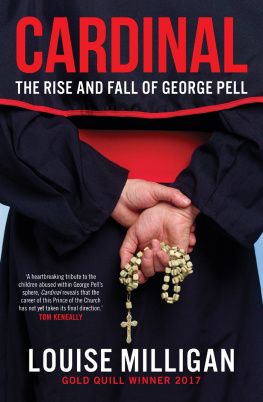

The Cardinal Makes His Appeal

27 February13 July 2019

With an introduction by George Weigel

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Quotations from George Cardinal Pells breviary are from The Divine Office , 3 volumes (Sydney: EJ Dwyer, 1974).

Cover photograph courtesy of George Cardinal Pell

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

2020 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

Introduction 2020 by George Weigel

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-448-4 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-64229-142-1 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number 2020945860

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

by George Weigel

This prison journal should never have been written.

That it was written is a testament to the capacity of Gods grace to inspire insight, magnanimity, and goodness amidst wickedness, evil, and injustice. That it was written so beautifully bears witness to the Christian character that divine grace formed in its author, George Cardinal Pell.

How and why the author found himself in prison for over thirteen months for crimes he did not commit, and indeed could not have committed, is another story, far less edifying. A brief telling of this tawdry tale will, however, set the necessary context for what you are about to read, even as it underscores just how remarkable this journal is.

On April 7, 2020, the High Court of Australia issued a unanimous decision that quashed a guilty verdict and entered a verdict of acquitted in the case of Pell vs. The Queen . That decision reversed both the incomprehensible trial conviction of Cardinal Pell on a charge of historic sexual abuse and the equally baffling decision to uphold that false verdict by two of the three members of an appellate court in the state of Victoria in August 2019. The High Courts decision freed an innocent man from the unjust imprisonment to which he had been subjected, restored him to his family and friends, and enabled him to resume his important work in and for the Catholic Church.

Close students of Pell vs. The Queen knew that the case ought never have been brought to trial. The police investigation leading to allegations against the cardinal was a sleazy trolling expedition. The magistrate at the committal hearing (the equivalent of a grand jury proceeding) was under intense pressure to bring to trial a set of charges she knew were very weak. When the case was tried, the Crown prosecutors produced no evidence that the alleged crime had ever been committed, basing their argument solely on the testimony of the complainanttestimony that was inconsistent over time and that was shown to have been deeply flawed. There was no corroborating physical evidence, and there were no witnesses to corroborate the charges.

To the contrary. Those directly involved in Melbournes cathedral at the time of the alleged offenses, two decades earlier, insisted under oath and during cross-examination that it was impossible for events to have unfolded as the complainant alleged: neither the time frame used by the prosecution to describe the alleged abuse nor the complainants description of the layout of the cathedral sacristy (where the crimes were said to have been committed) made sense. This extensive testimony in the cardinals defense was never seriously dented by the prosecution. Moreover, the sheer impossibility that what was alleged to have happened actually happened was subsequently confirmed by objective observers and commentators, including those who had previously held no brief for Cardinal Pell (and one who was a severe critic).

Pell vs. The Queen was also prosecuted in a way that raised grave doubts about the commitment of the Victoria authorities to such elementary tenets of Anglosphere criminal law as the presumption of innocence and the duty of the state to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. In this regard, Justice Mark Weinberg, the dissenting judge in the August 2019 appellate decision, made a crucial jurisprudential point while eviscerating his colleagues rationale for upholding Cardinal Pells conviction: by making the complainants credibility the crux of the matter, both the prosecution and Weinbergs colleagues on the appellate panel rendered it impossible for any defense to be mounted. Under this credibility criterion, no evidence of an actual crime was required, nor was any corroboration of the allegations; what counted was that the complainant seemed sincere. But this was not serious judicial reasoning according to centuries of the common law tradition. It was an exercise in sentiment, even sentimentality, and it had no business being the decisive factor in convicting a man of a vile crime and depriving him of his reputation and his freedom.

As Justice Weinbergs extraordinary, over two-hundred-page dissent was digested by jurists and veteran legal practitioners in Australia, and as the post-appeal lifting of a press blackout on coverage of the Pell trial exposed the thinness of the prosecutions case, a rising tide of concern among thoughtful people, convinced that a grave injustice had been done, could be felteven at a distance of thousands of miles from Melbourne. That concern may have been reflected in the decision by the High Court, Australias supreme judicial body, to accept a further appeal (which need not have been granted).

Similar concerns were evident from the bench in the sharp grilling of the Crowns chief prosecutor when the High Court heard the cardinals appeal in March 2020. That two-day exercise made it plain, again, that the Crown had no case that would meet the standard of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt; that the jury in the cardinals second trial (held because of a hung jury at his first trial) returned an unsafe and, indeed, insupportable verdict; and that the two judges of the Victoria Supreme Court who upheld that conviction (one of whom had no criminal law experience whatsoever) made grave errors of the sort that their colleague, Justice Weinberg, identified in his dissent.

The High Courts decision to acquit Cardinal Pell and free him was thus both just and welcome. The question of how any of this could have happened to one of Australias most distinguished citizens remains to be examined.

The vicious public atmosphere surrounding Cardinal Pell, especially in his native state of Victoria, was analogous to the poisonous atmosphere that surrounded the Dreyfus Affair in late-nineteenth-century France. In 1894, raw politics and ancient score-settling, corrupt officials, a rabid media, and gross religious prejudice combined to convict an innocent French army officer of Jewish heritage, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, of treason; Dreyfus was cashiered from the army and condemned to imprisonment in the fetid hell of Devils Island, off the coast of French Guiana. The Melbourne Assessment Prison and Her Majestys Prison Barwon, the two facilities in which George Pell was incarcerated, are not Devils Island, to be sure. But many of the same factors that led to the false conviction of Alfred Dreyfus were at play in the putrid public atmosphere of Victoria during a Pell witch-hunt that extended over several years.

The Victoria police, already under scrutiny for incompetence and corruption, conducted a fishing expedition that sought evidence for crimes that no one had previously alleged to have been committed; and, by some accounts, the police saw the persecution of George Pell as a useful way to deflect attention from their own problems. With a few honorable exceptions, the local and national press, abandoning all pretense to journalistic integrity and fair-mindedness, bayed for Cardinal Pells blood. Someone paid for the professionally printed anti-Pell placards carried by the mob that surrounded the courthouse where the trials were conducted. And the Australian Broadcasting Corporationa taxpayer-funded public institutionengaged in the crudest anti-Catholic propaganda and broadcast a stream of defamations of Cardinal Pells character (one of which was aired during the deliberations of the High Court).

Next page