As I drove eastwards on the M1 highway through the farms of Gippsland, the expansive fields rushed past and blended into the vast grey skies. There were few travellers along this slice of rural and coastal beauty in the south-east of Victoria on this autumn weekday in 2015, and I hovered on the 100 kilometre-per-hour speed limit, confident there would be little reason to slow or stop.

I was grateful for the journey time. A long drive ahead of knocking on someones door for a story is a gift. Its the perfect opportunity to relax and consider your approach, as you start mulling over the mindset of the person you want to talk to.

Ive always been a confident reporter but a nervous door-knocker. I need thinking time. Its an uncomfortable task to ring a doorbell and then ask the person who answers to tell you their deepest secrets, or perhaps relive a buried moment of trauma, then to depart as quickly as you arrived, scoop secured on a voice memo.

Its easier to phone, of course. News outlets have digital platforms so fast, so vast, they eat stories quicker than reporters can produce them. But going to someones home for a sensitive story, instead of calling them or sending a message on Facebook, is often the way to make a viable connection. To have a real-life conversation in person is often a better way to persuade someone to open up.

Better, definitely, but it still doesnt make the mission feel natural, or comfortable. Sometimes, after making your introduction, the door slams in your face amid expletives, threats and a report to the local police. You make a hasty, embarrassed retreat feeling shameful and small. Other times you find yourself invited in for tea and biscuits and treated like a visiting celebrity, which always comes with great relief. But you cant predict what will unfold until you knock.

Some reporters get such last-minute nerves that they knock the grass as its known in the trade, pretending to their editors the target wasnt in without even having tried to make contact. Ive never knocked the grass, but Ive been near enough to smell it.

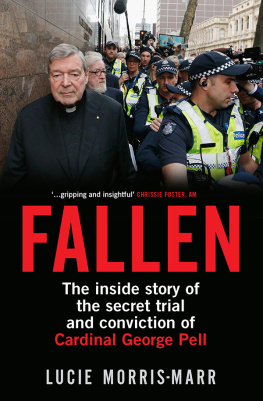

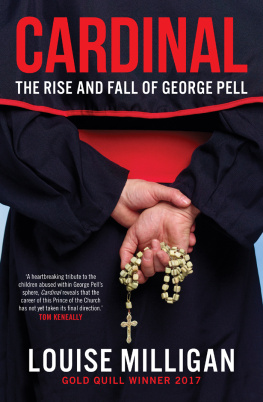

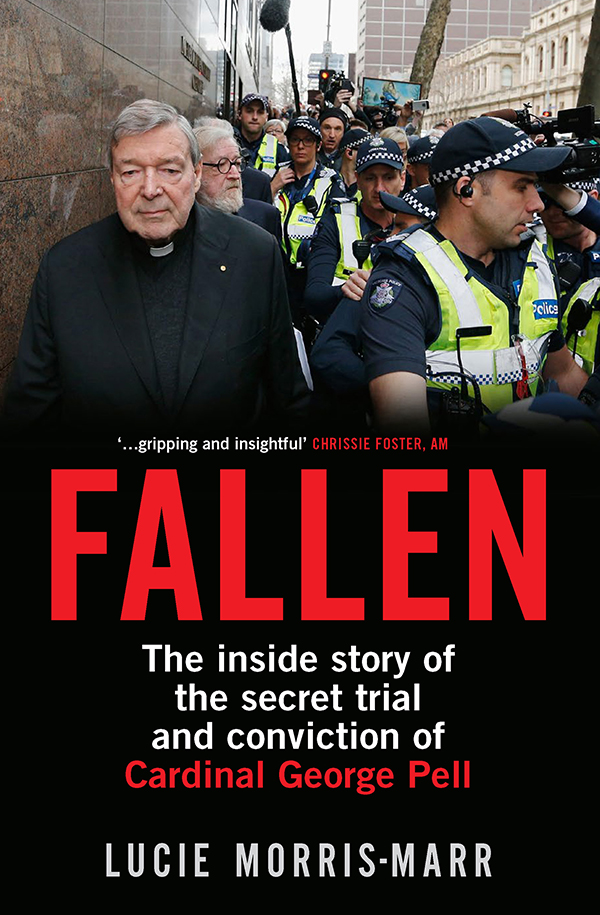

As you get more experienced, you start to only want to knock on the door if its really necessary, really vital to a bigger story or issue. I had already decided that this drive and this knock was very necessary indeed. It was critical, because behind the door was someone who may have some essential information about Cardinal George Pell.

The cardinal had fallen off my reporting radar somewhat until that point in April 2015. When Id been living in Sydney, Id known him as the citys archbishop. As my son was being born in July 2008, the streets were closed around the womens hospital in Randwick for Pope Benedicts grand visit for World Youth Day. A delighted Pell was front and centre, playing host to the whole, colourful event as over a million young people from 200 countries attended over several days.

Pell made a speech at the opening mass preaching the need for young people to practice self-control in their lives. The practice of self-control wont make you perfect, it hasnt with me, but self-control is necessary to develop and protect the love in our hearts and prevent others, especially our family and friends, from being hurt by our lapses into nastiness or laziness, he said.

He also struck a serious note and encouraged the young people gathered to do their duty, saying: To the young ones, I give a gentle reminder that in your enthusiasm and excitement you do not forget to listen and pray.

The event, controversially, cost the NSW government over $200 million. But for the Australian Catholic Church energised by the youthful PR boost, it was a huge success. With the eyes of the worlds media focused on the spectacle as Pells career was catapulted to new heights as he walked alongside the Pope.

It wasnt surprising that by 2014 the Prince of the Australian Church had moved to Rome as a permanent resident and a trusted adviser to the Pope. He had already been appointed by Pope Francis the year before to a group of nine senior cardinals, to advise on the government of the universal Church and to study a plan for revising the Apostolic Constitution of Roman Curia. At 73, Australias most senior Catholic was in the inner sanctum of power in the Vatican.

Pell was the new boy in town, working in a lavish sixteenth-century tower and enjoying the lofty title of the Holy Sees Prefect of the Secretariat for the Economy. There are a number of handy abbreviations for this elaborately named role, Gods treasurer being one of them. It was clear Dr Pell had become a very powerful man since packing his case in Sydney and getting on a plane to Italy. Very powerful indeed.

The hugely ambitious priest from the Victorian gold-rush town of Ballarat had scaled the heady heights of the Catholic career ladder: he was now in charge of his own vaults of gold; nuns brought him espressos and dainty Italian biscuits; home was a comfortable apartment at Number 1, Piazza Della Citta Leonina, just outside the main walls of the Vatican. In short, life and work for Pell in his new city was more than sweet, it was bella belissimo.

He was even being touted as a possible candidate to be the next Pope; he had participated in the conclave that elected Pope Francis over two days in March 2013 and obtained two votes in the first ballot, when one out of every five prelates got a vote. He then received one vote in the 2nd ballot and one vote in the third ballot.

One glowing article from the UKs Catholic Herald two months later concluded that Pell was an ideal new asset for the new pontiff.

It was reassuring to observe that, as a pillar of the church he [Pell] was open, direct and also humble. The reporter concluded, One can see why he will be a welcome member of Pope Franciss new committee.

So all was going swimmingly for the son of a Ballarat publican; Big George, as he was known in his younger years by fellow priests and parishioners.

All except for one troubling, irritating little caveat circling Pells impressive new life among the romantic cobbled streets, servants and Da Vinci paintings. It was a trailing cloud of scandal on his otherwise impressive CV regarding what he may have seen, heard or ignored regarding historic child sexual abuse in his homeland. Particularly, what he may have witnessed during his time living in his hometown of Ballarat, which had increasingly become recognised as the dark epicentre of clergy wrongdoing towards minors, and what he may have known regarding paedophile priests while working in the Archdiocese of Melbourne.

The anger and innuendo among survivors and advocates had followed him like an annoying wasp. No matter how many miles he travelled or how powerful he became, the questions from back home, including those from two official abuse inquiries, would follow his every step. They had started as whispered allegations and outrage, but had picked up volume, and very soon they would get even louder.

Pells life and career were about to change direction. And so was mine.

Pells name had come up completely by chance the morning before the drive to Gippsland. It was a Monday in my second week as a reporter on the Herald Sun newspaper in Melbourne, a top-selling Murdoch tabloid. My priority at that point was just getting stuck firmly into exciting and important stories, going back on the road as a reporter as I had done in my twenties in London before moving to Australia.

Would your prison contact be able to help with something to do with George Pell? asked Chris Tinkler, the head of news at the time, during a brief chat by his desk.

Next page