Table of Contents

Also by Michael Willrich

City of Courts: Socializing Justice in Progressive Era Chicago

For Wendy

PROLOGUE

NEW YORK, 1900

Manhattans West Sixty-ninth Street no longer runs from West End Avenue to the old New York Central Railroad tracks at the Hudson Rivers edge. In the space now occupied by aging high-rise condominium towers and their long shadows, there once stood a low-slung street of tenements and houses. At the turn of the twentieth century, it was said to be the most thickly populated block in the most thickly populated city in the United States of America. Someone called it All Nations Block, and, being a pretty fair description of the place, for a while the name stuck.

A brisk walk from the fashionable hotels of Central Park West, All Nations Block was a rough world of day laborers, bricklayers, blacksmiths, stonemasons, elevator runners, waiters, janitors, domestic servants, bootblacks, tailors, seamstresses, the odd barber or grocer, and, far outnumbering them all, children. Each morning, the children streamed east to Public School No. 94 at Amsterdam Avenue or to the crowded kindergarten run by the Riverside Association at 259 West Sixty-ninth Street. That same foot-worn building housed the charitable associations public baths; in any given week, four hundred men or more paid a nickel for a towel, a piece of soap, and a shower that had to last. The tenement dwellers of All Nations Block did not choose their neighbors. It was the kind of place where an itinerant black minstrel actor, feeling feverish and far from his southern home, could find a bed for a few nights, in a great warren of rooms whose other occupants were Italian, Irish, Jewish, German, Swedish, Austrian, African American, or simply, so they said, white.

The men of the West Sixty-eighth Street police station knew the block and its ways well. The policemen came when the neighbors brawled, when jewelry went missing in an apartment by the park, or when the Irish boys of the All Nations Gang got too rough with the Chinese laundryman on West End Avenue. The police came once again on the night of November 28. A forlorn and drunken stonemason named Michael Healy, imagining himself to be under attack in his room (Theyre after me, he had shouted, See those black men!), had hurled himself through a fourth-floor window and fell, in a cascade of glass, to, or rather through, the ground below. The Irishman made a two-by-two-foot hole in the surface, breaking through to some long-forgotten trench near the buildings cellar. A neighborhood boy ran to the Church of the Blessed Sacrament on West Seventieth Street and summoned a priest. When the priest arrived, he crawled right through the hole and into the trench, which was already crowded with police, an ambulance surgeon, and Healys broken but still breathing body. Before this subterranean congregation, the priest administered last rites. That was the way things went on All Nations Block. It was the night before Thanksgiving, the first of the new century.

New Yorkers of a certain age would remember that Thanksgiving as the day the smallpox struck the West Side. The outbreak had in fact started quietly a few days earlier, on All Nations Block. The city health officers found the children first: twelve-year-old Madeline Lyon, on Tuesday, and on Wednesday, a child just across the street, identified only as a white boy four years old. For the health officers to diagnose the cases with any confidence, the children must have been suffering for days, with raging fevers, headaches, severe back pain, and, likely, vomiting, followed by the distinctive eruption of pocks on their faces and bodies. Once the rash appeared and the lesions began their two-week metamorphosis, from flat red spots to hard, shotlike bumps to fat pustules to scabs, the patients were highly contagious. The health officers removed the children, stripped their rooms of bedding and clothing, and disinfected the premises.

The health department followed the same procedure with the five other cases that were reported elsewhere in Manhattan within hours of the Lyon case. One was a white domestic servant named Mary Holmes, who worked in an affluent apartment house on West Seventy-sixth Street. The other four were black, evidently from the neighborhood of the West Forties. They were Adeffa Warren, Lizzie Hooker, Susan Crowley, and Crowleys newborn daughterthese last two had been removed in haste from the maternity ward at Bellevue Hospital. Through interviews, health officers had established that the four black patients had come into contact with an unnamed infected negress, who remained at large. How any of these patients might have been connected to the children on West Sixty-ninth Street, about a mile and a half uptown, remained uncertain. But the authorities were working on the assumption that the outbreak started on All Nations Block.

The officers of the internationally renowned New York City Health Department, medical men given broad powers to police and protect the public health in one of the worlds most powerful centers of capital, were not easily shaken by the odd case of smallpox among the wage earners. Now and then an infected passenger got past the U.S. government medical inspectors at Ellis Island or crossed into the city on one of its many railroad tracks, waterways, roads, footpaths, or bridges. Most New Yorkers had undergone vaccination for smallpox at one time or anotheron board a steamship crossing the Atlantic, in the public schools, in the workplaces, in the city jails and asylums, or, if they possessed the means, in their own homes under the steady hand of a trusted family physician. When an isolated case of smallpox triggered a broader outbreak, the health officials took it as an unmistakable sign that the populations level of immunity had begun to taper off, as it did every five to ten years. The time had come to sound the call for a general vaccination. We are not afraid of smallpox, said Dr. F. H. Dillingham of the health department, when the news broke that smallpox had reappeared on Manhattan. With the present facilities of this department we can stamp out any disease.

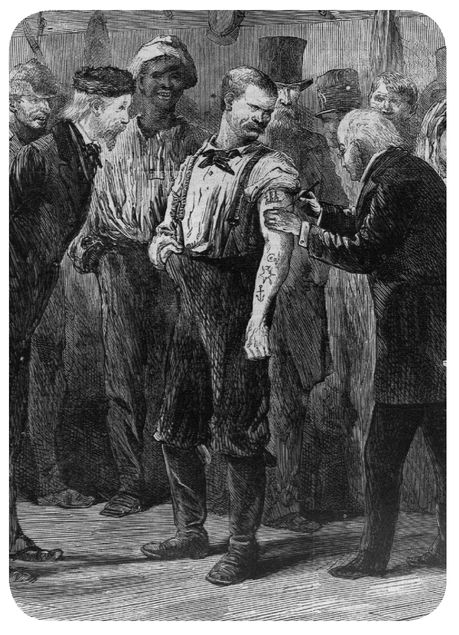

On Thanksgiving Day, as the Columbia University football team took the field against the Carlisle Indian School and three thousand homeless people lined up for a hot dinner at the Five Points House of Industry, a vaccination squad from the health departments Bureau of Contagious Diseases moved into West Sixty-ninth Street. The four doctors began a quiet canvass of All Nations Block, starting with the immediate neighbors of the infected children. Health department protocol called for a thorough investigation of each case, in order to trace its origin, followed by the immediate vaccination of all possible contacts. In a place as densely inhabited as All Nations Block, everyone would have to bare their arms for the vaccine.

With a willing patient, the vaccination operation, as doctors called it, lasted just a minute or two. The doctor took hold of the patients arm, scoring the skin with a needle or lancet. He then dabbed on the vaccine, either by taking a few droplets of liquid lymph from a glass tube or using a small ivory point coated with dry vaccine. Either way, the vaccine contained live cowpox or