Acknowledgements

My warmest thanks for help in writing this book are owed to someone I sadly never met: the late Robert Dimsdale, direct descendant of Thomas and an expert on his ancestors extraordinary life and the wider history of his remarkable family. His meticulous research is the foundation of this account. I am immensely grateful to the Dimsdale family, particularly Annabel, Edward, Wilfrid and Franoise, for their generosity in sharing their collection of Thomass correspondence, medical notes and other papers with me, and trusting me to tell his story. Their help, given amid all the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, was invaluable.

Equally generous was Professor Anthony Cross of Fitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, who passed on to me his bursting file of documents relating to the story of the Empress and the English doctor. His findings gave me a flying start as I began my own research, and his enthusiasm for the lives of the many British citizens who passed through Russia in the eighteenth century captured my imagination.

Many other people freely lent me their time and expertise. Jonathan Ball, Professor of Molecular Virology at the University of Nottingham, was an especially helpful guide on the history of viruses and vaccines, while Professor Ben Pink Dandelion, Director of the Centre for Postgraduate Quaker Studies at the University of Birmingham, shed invaluable light on Thomas Dimsdales Quaker heritage. Owen Gower, manager of Dr Jenners House, trawled the museums archives for me when it was not possible to visit, while authors Michael Bennett, Gavin Weightman and Jennifer Penschow generously shared findings from their own research into the history of inoculation. Helen Esfandiary shared her expertise on mothers and inoculation in elite Georgian society, while Jon Dunn gave me wise authorial advice and ensured the Shetlands made it into this book.

In St Petersburg, Natalia Sorokina provided a home away from home and a sense of personal connection to the city, while Valentina Danilovas historical and cultural expertise brought the Hermitage and the royal estates around St Petersburg to life. Thank you to the curators of the Voltaire Library for hunting down texts on inoculation, complete with Voltaires handwritten notes, and to Harriet Swain for putting up with my relentless palace-hopping.

Back in the UK, I am very grateful to Gill Cordingley for her tour of Hertfords top Dimsdale locations and the loan of her books. Thanks too to Marilyn Taylor and Jean Purkis Riddell, and to Kathie Moy for the introductions. Bonnie West of the Hertfordshire Archives located important Quaker records for me when the archive was closed during the pandemic. Archivists at Yale University, the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (RGADA), the Library at Friends House in London, the Royal Society of Physicians, the University of Aberdeen and University College London (home to the archive of St Thomass Hospital) were all exceptionally helpful in difficult conditions. Hayley Wilson dug out archival treasures and joined me on research visits, while Martyn Everett directed me to the wonders contained in the Gibson Library in my home town of Saffron Walden.

Colleagues at Gonville & Caius College and many others at Cambridge offered me encouragement and expert knowledge. Thank you in particular to Hugo Larose and Valerio Zanetti, and to Dr David Secher. I am also greatly indebted to Tatiana King, who provided the Russian translations for the book and worked through Ospa i ospoprivivane with me. Never have so many hours been spent on Zoom talking about pustules.

Many friends patiently put up with my inoculation fixation. Thank you especially to Sheila Gower Isaac, Victoria Skinner, Alison Mable, Clare Mulley, Sarah Stockwell, Katherine Whitbourn and Joyce Harper. My former Guardian colleague Patrick Barkham and Rebecca Ostrovsky of Pushkin House helped set me on my way and Rachel Wright encouraged me throughout. Simon and Katya Cherniavsky lent me their home and, with the expert help of Irina Shkoda, translated eighteenth-century handwritten Cyrillic, while Tav Morgan kindly paid my RGADA bill (cash only) in Moscow.

Past influences were important too. Beryl Freer, my school history teacher, set alight my interest in Catherine the Great. Sadly she died shortly before publication of this book; I would have loved to show it to her. Sin Busby, too, is no longer with us, but her kindness and her wholly original books had a great impact on me.

When I first proposed this book to Cathryn Summerhayes, my agent at Curtis Brown, the Covid-19 pandemic was just weeks away. Neither of us knew the story would soon have new resonance. I am immensely grateful for her faith in me. Sam Carter, my editor at Oneworld, has been exceptionally patient and generous, supporting me in writing and editing during lockdown and beyond. Holly Knox and Rida Vaquas were perceptive and meticulous. The book is much improved thanks to all of you; its shortcomings are all mine.

Lastly, thank you to my family. Pauline, David and Tom Ward and Robert Smith read, advised and encouraged. Most of all, Liam, Ailis, Maeve and Ned put up not only with a modern pandemic but with a partner and mother obsessed with a previous one. And Rosie, Milo and Mishka sat patiently by my side, wondering if I would ever get up and walk them.

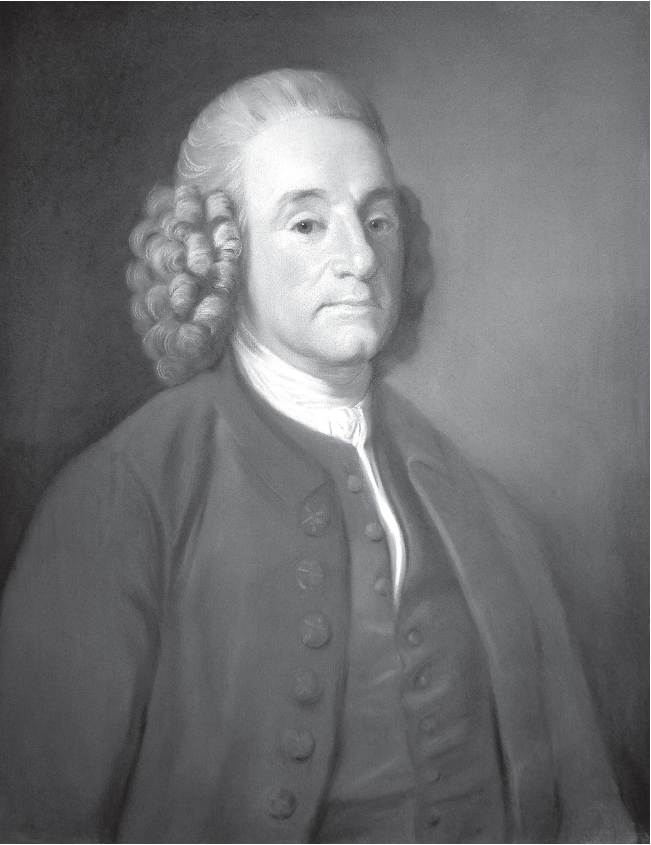

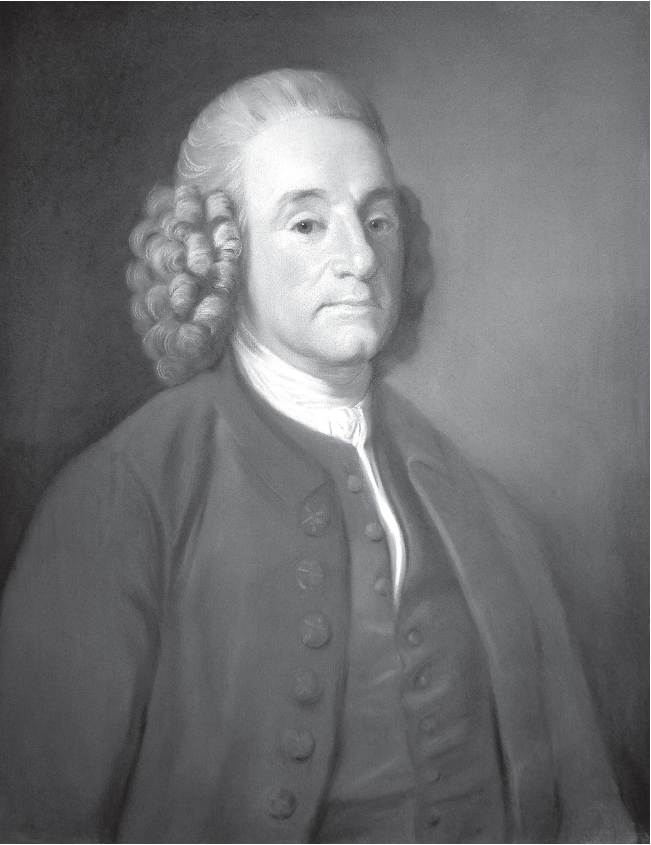

Baron Thomas Dimsdale, Portrait by Carl Ludwig Christinecke, 1769.

Bronze medal reading She herself set an example, commissioned by Catherine to commemorate her inoculation. Engraved by Timofei Ivanov.

The Doctor

A gentleman of great skill in his profession, and of the most extensive humanity and benevolence.

Little Berkhamsted Parish Register, 1768

The birth of Thomas Dimsdale was recorded in the form of a neat, handwritten certificate. The new baby came into the world on 29 May 1712, the sixth child and fourth son of John and Susannah Dimsdale of the parish of Theydon Garnon in the county of Essex, England. The document was signed by seven witnesses.

A second scrap of paper also listed on one side the birth dates of Thomas and some of his siblings. On the other was something unexpected: a medical recipe. To cure kidney stones, it instructed, mix saffron, turmeric, pepper and elder bark into three pints of white wine, and take the mixture first thing in the morning and last thing at night. It is proper, the note concluded, to take a vomit first.

The scribbled remedy was one of many in the Dimsdale household. Thomass father, John, was a doctor, as his own father, Robert, had been before him. A generation further back, at the time of the English Civil War, Thomass great-grandfather an active supporter of the Parliamentarian cause had combined running an inn in the Hertfordshire village of Hoddesdon with a trade as a barber-surgeon. John Dimsdale had established himself in practice at Epping, a small market town lying among pastures and scattered hamlets in the countryside some seventeen miles north-east of London, just at the tip of the long strip of ancient forest that still bears its name. There, as well as treating those who could afford to pay for his services, he worked on behalf of the Overseers for the Poor of Theydon Garnon, providing basic healthcare for the many impoverished households whose only safety net was parish welfare.

The home-made birth certificate offered another clue to the Dimsdales heritage. The family were Quakers: members of the dissenting Puritan sect that had emerged from the Civil War the century before. Refusing to recognise the authority of the Church of England and its hireling priesthood, members of the Religious Society of Friends, as the Quakers were formally known, rejected parish registers and kept their own independent records of births, marriages and deaths. God was within every individual, the sect believed, and its worshippers trembled at his word.

Next page