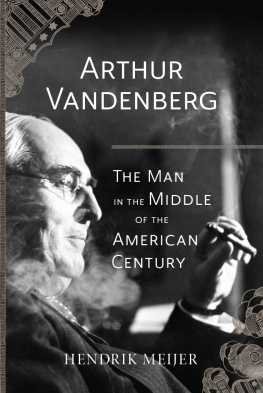

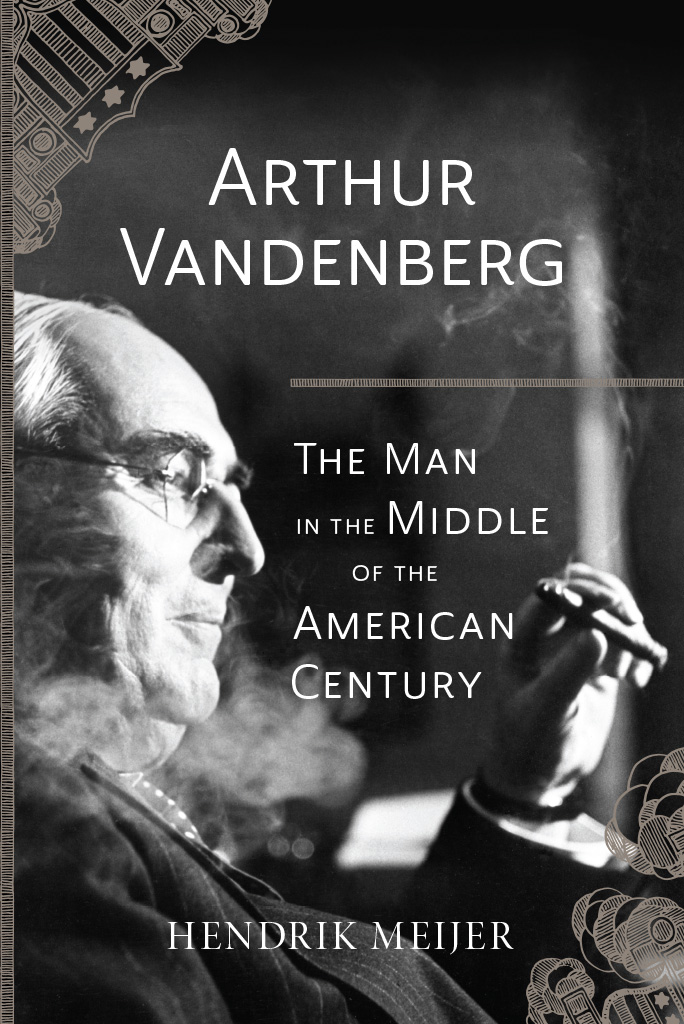

Arthur Vandenberg

The Man in the Middle of the American Century

HENDRIK MEIJER

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by Hendrik Meijer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-43348-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-43351-6 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226433516.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Meijer, Hendrik G., 1952 author.

Title: Arthur Vandenberg: the man in the middle of the American century / Hendrik Meijer.

Description: Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015718| ISBN 9780226433486 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226433516 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Vandenberg, Arthur H. (Arthur Hendrick), 18841951. | LegislatorsMichiganBiography. | United StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E748.V18 M45 2017 | DDC 328.73/092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015718

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Liesel

The sense of danger must not disappear:

The way is certainly both sharp and steep,

However gradual it looks from here;

Look if you like, but you will have to leap.

W. H. Auden, from Leap Before You Look, 1941

What a pity he is so dreadfully senatorial!

said Mrs. Lee; otherwise I rather admire him.

Henry Adams, Democracy

CONTENTS

The American Senator drank a little more than he could conveniently manage, wrote his hostess, the wife of the Argentine ambassador, in her diary in 1934. He had emerged from the embassy library, pale and unsteady after brandy and cigars. He stumbled over the Aubusson carpet, knocked against a slender French chair, but managed to right himself in order to walk out... in proper senatorial dignity. Why is it, she mused, that the American man has never been able to drink? Or is it that he has never learned to drink? Arthur Vandenberg was nothing if not dignified, but she might have asked what else the imposing senator with the bright, dark eyes had to learn, for the answer would have foretold momentous lessons for the American people, too.

Vandenberg knew how to oppose things, certainly. But that was easy. One could just say no. He had said no to FDR and much of the New Deal. He had opposed as well any compromise of American independence in foreign policy. He pounced on any hint of a treaty or alliance, any foreign entanglement, in a world growing ever more dangerous.

Within five years the ambassadors wife noted in the margin of her diary, alongside the earlier entry, How this particular Senator has changed! He has become little by little a man of the world. Never again had she seen him tipsy. Indeed, his prospects were bright: He is, at the moment, she wrote, the leading aspirant for the Republican nomination in 1940. She wrote this late in 1939. Hitler had invaded Poland only weeks before, triggering a second world war. As leader of the Senates isolationist bloc, Vandenberg had fought unsuccessfully to keep the United States out of war. His opposition brought him notoriety and stature, but he had sacrificed his electability. Wendell Willkie swept to the nomination instead.

Yet Vandenbergs odyssey had only begun. Five years later, in 1945, as the war neared its end, his speech heard round the world changed his lifeand the American political landscape. In it he proposed a postwar treaty among the victorious allies, the very foreign entanglement that he, like George Washington and so many who followed him, had been so wary of. The isolationist had turned world statesmanand the capitals darling.

In quick succession came his appointment as delegate to the United Nations organizing conference, his role in postwar peace talks, his success in steering through Congress the Marshall Plan and the resolution to create the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. With George Marshall, Vandenberg helped save a continent. The Economist urged Europeans to consider the christening of a Rue Vandenberg or a Vandenbergplatz. Harry Truman was in trouble without him.

All too soon, peace gave way to the Cold War, with the Soviet Union and its satellites ranged behind the infamous Iron Curtaina coinage Vandenberg employed before Winston Churchill made it famous. The Kremlin decried the sinister influence of the senior senator from Michigan. He was a bogeyman, the devil on Trumans shoulder, an exemplar of American imperialism. For the Western world, however, Vandenberg became the voice of an American people groping for new answers, for a shared voice in foreign policy, for a politics that stopped at the waters edge.

When Truman addressed a joint session of Congress to urge passage of the Marshall Plan, Vandenberg, as president pro tempore of the Senate, occupied the vice presidents seat above him on the dais. The presidents speech fell flat. This was a setting for a roaring lion, high in spirits... , bursting with determination, wrote a reporter for Time. In contrast to Truman, A Vandenberg, a Roosevelt or a Churchill would have played Congress like a harp, and spoken in tones of thunder, defiance, confidence. Todays reader might find that sequence of statesmen somewhat jarring. Roosevelt, Churchilltheir eminence is understood. But Vandenberg?

Not only did the senior senator from Michigan reflect and express the anxieties of the American people; he worked with politicians across the aisle in a search for national security. He was trusted by colleagues and presidents and no small portion of the press. He had come by the sort of gravitas that led some to think him the steadiest leader in a time of crisis. A young Democratic senator named William Fulbright had the temerity to suggest that the untested President Truman, thrust into office with so little preparation, appoint the Republican Vandenberg as his secretary of stateand then resign. In the absence of a vice president, Vandenberg would succeed him. (Truman, not amused by the suggestion, dismissed the ideas proponent as Senator Halfbright.)

One pundit proposed Arthur Vandenberg for president of the world. Edward R. Murrow called him the central pivot of the era. With the advent of the Cold War, Americans turned to him for guidance and wisdomfor the very security that had been his lifelong obsession.

Decades later, the qualities that defined him are again in demand. But who was he?

The Cause of Ruin

We hunt the cause of ruin, add,

Subtract, and put ourselves in pawn;

For all our scratching on the pad,

We cannot trace the error down.

Theodore Roethke, from The Reckoning, 1940

CLASS OF 1900

The Panic of 1893 ruined the brisk harness trade of Aaron Vandenberg. His son, Arthur, nine years old, was profoundly affected. I had no youth, he insisted decades later, with typical hyperbole. I had one passionto be certain that when I grew up I would not be in the position my father was.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).