Lawrence J. Haas

2016 by Lawrence J. Haas

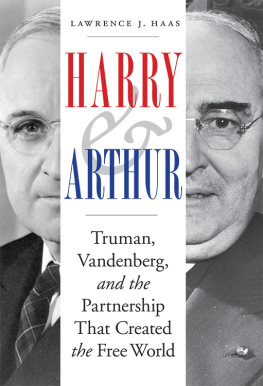

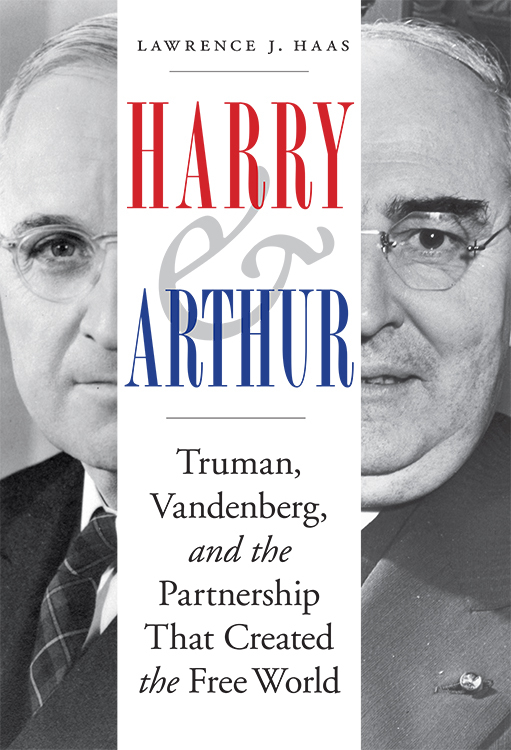

Cover image: Truman photo (left) courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ 62-13033; Vandenberg photo (right) The Granger Collection, New York

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Names: Haas, Lawrence J.

Title: Harry and Arthur: Truman, Vandenberg, and the partnership that created the free world / Lawrence J. Haas.

Description: Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, 2016. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9781612348124 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : United StatesForeign relations19451953. | Truman, Harry S., 18841972. | Vandenberg, Arthur H. (Arthur Hendrick), 18841951.

Classification: LCC E 813 . H 23 2016 | DDC 327.73009/04dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015036855

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

W RITING A BOOK IS one thing; writing it in a timely fashion is quite another. I never could have done the latter without the invaluable assistance of a dozen talented research interns from the American Foreign Policy Council ( AFPC ), the Washington think tank with which Im affiliated: Joshua Truman, Megan Carey, James OBryant, Jared Swanson, Kayla Scott, Sarah Reynolds, Anabel Hallewell, Cameron Harris, Lauren Danen, Jason Czerwiec, Ben Schwartz, and Drew Jansen. These talented young professionals each spent a few months assisting me and, over the course of nearly three years, tracked down vital sources of informationnewspaper and magazine accounts from the late 1940s, journal articles, government reports, and so onand fact-checked the words I put to paper. I thank them for their work, and I thank AFPC President Herman Pirchner, Vice President Ilan Berman, and Director of Operations Richard Harrison for making them available.

I also thank Ilan Berman, Richard Cohen, Mark Fife, Marjorie Segel Haas, Ben Schwartz, and Drew Jansen for reading the manuscript, offering suggestions, catching typos and grammatical problems, and pinpointing factual errors that could have proved embarrassing. Any errors that still crept into this book are my fault alone.

Peter Bernstein, my agent and an accomplished author and editor, improved this book immensely with his suggestions for both my book proposal and the book itself. The structure and focus of Harry and Arthur owe much to our conversations. Whatever its deficiencies, this book is far better than it would have been without Peters prodding. The book is also better due to the efforts of many wonderful people at Potomac Books, on both the editorial and marketing sides, who worked with great care to turn a raw manuscript into a finished product of which I could be proud.

No one has more patience than my wife, Marjie, and my daughter, Samantha. As much as possible, I try to research and write my books while theyre asleep or busy with their own things, but my work invariably impinges on our family time. I appreciate their willingness to tolerate it more than I can ever express. The best I can do is dedicate this book to them as a heartfelt expression of my love.

April 1945

O N THE MORNING OF April 12, 1945, Harry Truman, the vice president of the United States, and Arthur Vandenberg, the top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, awakened to a world in turmoila world that, with Franklin Roosevelts death later that day, they would inherit.

World War II was fast approaching its end, with U.S. troops slicing through Germany from the west and Soviet troops advancing from the east. With the Nazi regime collapsing, more of its liberated victimsprisoners of war, slave laborers, and concentration camp survivors; mostly men but also women and childrenwere wandering the streets, desperate for food, clothing, shelter, or a way out of Germany. Gaunt, dirt-caked, lice-infested, and malodorous, their skin sagging from skeletal bodies, they relayed tales of almost unimaginable horror. In Britains House of Commons, members merrily traded premature rumors that Hitler was dead. In France, the lights of Paris had returned recently for the first time since the war began to celebrate Allied victories on the western front, illuminating the Arc de Triomphe and Cathedral of Notre Dame, the Champs-Elysees and Place de la Concorde. In the Pacific, U.S. forces were progressing steadily against Imperial Japan, claiming land on nearby islands as Japanese citizens committed suicide in hordes rather than face capture.

For Truman and Vandenberg, however, the prospect of victory offered only limited satisfaction. As they could see, an America that was desperate for a reprieve from global tumult would not enjoy one. Already, the Soviet Union was presenting a huge new challenge for the United States, as the allies of war were fast becoming the rivals of an emerging postwar world. With misery and want plaguing vast stretches of Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and beyond, Moscow and its Communist minions were seeking to exploit the chaos and expand the Soviet Empire first across Eastern Europe and then elsewhere. Attitudes about the Soviets were hardening in Washington where opposition grew to more Lend-Lease aid for Moscow, and across the country where Catholic leaders and Polish Americans condemned Soviet activities in Eastern Europe.

If Truman and Vandenberg had read the cables between FDR and Joseph Stalin in the weeks before Roosevelts death, they would have seen that U.S.-Soviet relations had deteriorated even more than they knew. In his final days, FDR complained bitterly that, in establishing puppet regimes in Eastern Europe, Stalin was breaking his promises at the Yalta Conference of February to allow for free elections in Poland and elsewhere. He also protested that, in Soviet-held territories, Soviet soldiers were preventing American soldiers from helping U.S. prisoners of war, some of whom were ill or wounded. The day before his death, FDR advised the State Department that it had higher priorities than the Soviet request for a $6 billion loan. Stalin, meanwhile, accused FDR and Britains Winston Churchill of seeking a separate peace with Germany to spare the lives of U.S. and British soldiers while allowing Russian soldiers to continue dying. Suspicious of U.S. and British motives, Stalin expressed his irritation by announcing that his foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, would not attend the organizing conference of the United Nations, a top Roosevelt priority, which was scheduled to begin in San Francisco on April 25.