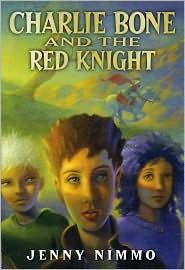

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Yaw Adomakoh (aka Daddy).

To Rebecca Bowen for helping with the diagrams of the Circe.

To Francesca Brill for introducing us to Mabel.

To Jacob Yeboa and Mrs. Elizabeth Adomakoh for help with the Twi

and Tuwe tuwe, mamuna tuwe tuwethe traditional Ghanaian

childrens song that Aneba sings.

To Fred Van Deelen for the maps and diagramsuse a magnifying glass!

To Paul Hodgson for copying out the music so elegantly.

And special thanks to Robert Lockhart for the beautiful tunes. If you like the Lionboy tunes, and want to play them on the piano, you might like to know hes written more, including Pirouettes Flying Habaera, El Diablo Aeros Highwire Violin Melody, and a rather scary number called Hello Charlieboy, Rafi Calling... Theyre published by Faber Music Ltd: Visit www.fabermusic.com for details.

And thanks to all the ladies at Dial: especially Lauri Hornik for her patience with our different ways of pronouncing tomato, Katrina Weidknecht, Nancy Paulsen, and Kimi Weart for the golden cover (and the pink skull ring).

And to the agents: Derek Johns, Linda Shaughnessy, Sylvie Rabineau, Rob Kraitt, Teresa Nicholls, Anjali Pratapso tough on our behalf! So nice to deal with! So many of them!

a cognizant original v5 release october 14 2010

CHAPTER 1

One Saturday afternoon in September Charlies mum was on a ladder in the backyard, doing things to plants halfway up the wall. Charlie didnt know what, or care. He liked the yard, the gorgeous honey-lemon smell of the flowers, and the great Christmas tree that hung over the back wall, with its shiny silver and green and purple fruits that he would harvest toward midwinter and sell at the market. He liked climbing around in the tree and in the ruins beyond, running down to the river, and talking to the cats that lived down there. But he didnt care what his mum was doing on the ladderuntil he heard a shriek and a clatter and a rude word, and he ran out to see.

His mum was on all fours, on the fallen ladder, on the ground, with festoons of the honey-smelling plant around her, her red hair wild and her face as white as ice.

Stupid, stupid, she was muttering.

No youre not, said Charlie. He offered her his hand and she pulled up to her feet, wincing. You wouldnt be a professor if you were stupid.

Clever people can do stupid things, she said. Let me into the house.

She hobbled inside and Charlie followed, worried but not worried, because his mum was the strongest, cleverest, bravest person in the world, apart from his dad, of course, and if anyone could handle falling off a ladder, she could.

Owwwww, she said. Charlie had already passed her the aloe, a piece of chocolate, and a small bottle of her secret shock remedy, which she made in her laboratory and which smelled of comfort and brandy and sweet winter herbs.

Best take a look, she said, and slid carefully out of the long leather breeches she always wore for outdoor work.

Owww, they both said, at the sight of the raw red scratches, the pinky purple swellings, and the nasty gashes that adorned her shin. Charlie handed over a clean paper towel and Mum dabbed at her wound.

Bring me some Bloodstopper Lotion, she said. Twenty-seven Red. Its in the rack. She handed Charlie the keys to her lab. Charlie smiled. Mum, Professor Magdalen Start, PhD, MD, PQRST, LPO, TP, kept her laboratory locked on strict instructions of the government, indeed of the Empire, because her work was so important that no one was to be allowed to know anything about it. Except of course for Charlies dad, Aneba Ashanti, Doctor of Endoterica and Tropical Sciences at the University of Accra in Ghana (currently on sabbatical at London University), Chief of Knowledge of all the Tribes of Akan, and Brother of Lions, who knew all about it because they worked together. Charlies dad knew everything that had ever been known about the plants of the West African forests, what they were good for, and what was good for them.

Your mum and I have different ways of knowing about the same thing, Dad would say. Very good system.

Charlie was honored. Every day these days he was allowed to do new things: new things that showed they realized he was growing up. Last Christmas hed been allowed to sell the shiny fruit at the market by himself, alone; on his way home from his lessons he was allowed to hang out for a while at the fountain, drinking sherbets and playing football or oware with the other big kids. And now he was allowed to fetch a lotion from his mothers lab. It felt good, being big.

In the rack by the door, Mum said with a little smile.

Hed been inside the lab before, of course. As a baby, after theyd come here to London from Africa, hed practically lived in there. While Mum worked, mixing and smelling and flicking between her burners and her computer screen, he would paddle around the place in a sort of pair of shorts hung on a wheeled frame: He could scoot and whiz, and once disappeared completely under a table, so Mum couldnt find him. Hed loved his shorts on wheels.

He loved the lab too. Because it was in a separate shed in the backyard, it had always seemed like a different world. Pushing open the door now, he got a waft of the smell of it: somewhere between a cake baking, old books, sweet strong incense, and underneath it the hard cold smell of science. It looked like it smelled. The walls were old and paneled with well-polished dark wood. The tables to the left were gleaming steel with glass cupboards, VDT screens and instruments of the most precise and modern specifications, while to the left a huge old wooden table stood empty except for a massive globe beneath a rack of hanging dried herbs. Along the back wall were stacked shelf upon shelf upon shelf of booksancient leather-bound tomes, colorful paperbacks, smart-looking hardbacks, parchments laid out flat, and scrolls, rolled tight and piled carefully, plus CD-roms and DVDs, and old, old thick black vinyl discs, which played on a machine with a huge curling horn. It seemed to Charlie that all the knowledge in the world, past and present, lived in his mothers laboratory, and if it didnt you could find out here where it did live.

By the door was a tall flattish wooden rack, made up of rows of shelves. On each shelf was a row of small, shiny, colored glass bottles, held in place by a little wooden bar along the front. If you looked carefully you could see that the color was not in the glass, but in the contents of the bottle, and they were arranged in order of color like a rainbow: Red Orange Yellow Green Blue Indigo Violet. Charlie craned up to where the reds began in the top left-hand corner, and scanned along the shelves looking for 27 Red. There it was: a deep crimson, blood-colored, only not so thick-looking. He reached up to take it and, giving the lab a last yearning look, took it back to where his mother was waiting in the kitchen.

Thank you, sweetie, she said, and was just about to lift the lid and drip a drop of the lotion onto her still-bleeding wound, when she hesitated.

Bring me a pen and paper, she said suddenly.

Charlie fetched one of the strong swirling glass pens that they used for every day, and the green kitchen ink, and a scrap of envelope.

Proper paper, she said, and he brought a piece of heavy clean parchment from the drawer.