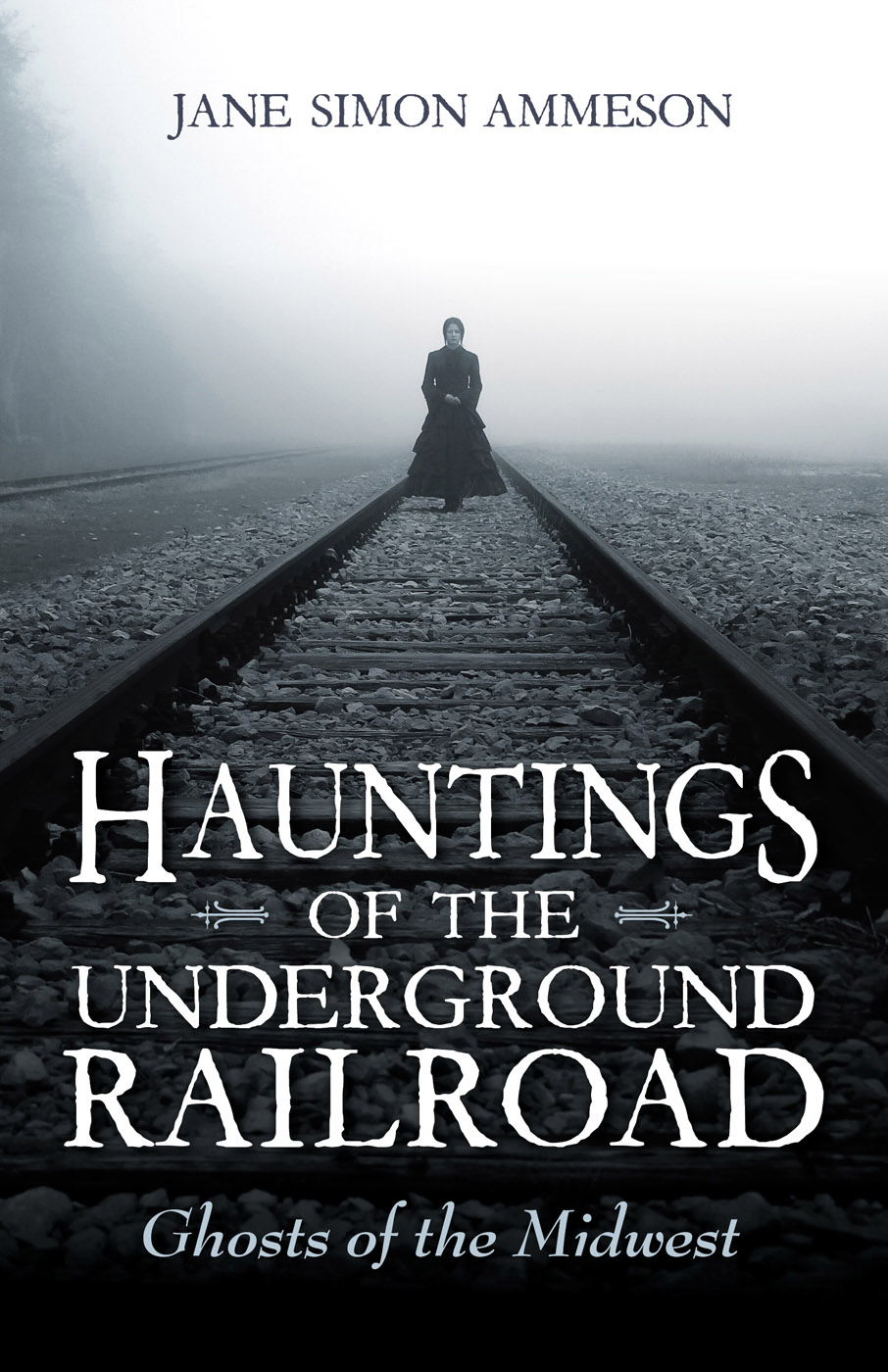

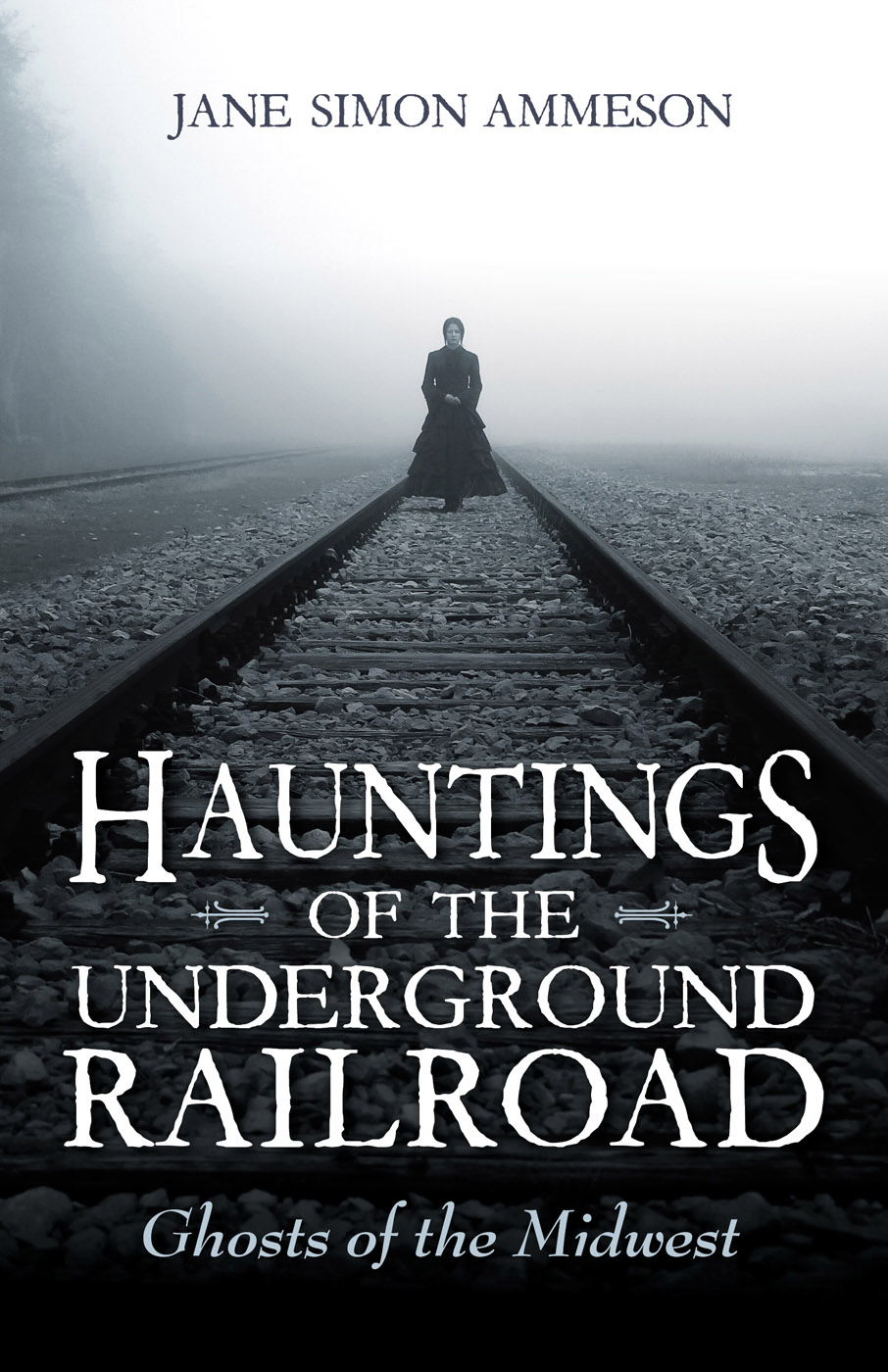

HAUNTINGS

OF THE

OF THE

UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD

HAUNTINGS

OF THE

OF THE

UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD

Ghosts of the Midwest

JANE SIMON AMMESON

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Jane Simon Ammeson

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-03128-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02982-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-03129-7 (ebook)

12345222120191817

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A COLD DAMP fog descends as the whistle of a steam locomotive sounds off in the distance. Clocks and watches stop, making time stand still as the nine-car Lincoln Special emerges into sight. This isnt the original Lincoln funeral train that left Washington, D.C., on April 21, 1865, carrying the bodies of the 16th president and his 11-year-old son on a 1,654-mile journey, the reverse of the one Lincoln had taken from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., in celebration of his election just four years earlier.

Instead, its a ghost train, following the same schedule, arriving at each stop on the same day and time as on Lincolns final journey. Want to see the Lincoln Special go by? Pick a former stop, preferably one where modern civilization seems far away, and wait. Funeral music and metal wheels on metal rails announce the arrival of the truly skeletal crew manning the engine house and stoking the fires as phantom Union soldiers continue, as they have for more than 150 years, to stand sentry over the coffin of their fallen president.

Just north of Indianapolis, in Westfield, a Union soldier walks the perimeter of the Anti-Slavery Friends Cemetery, stopping at a gravesitethat of a soldier slain in the last days of the war. Whose grave is he guarding? Is it that of a comrade gone too soon in battle? Or is it his own?

President Abraham Lincolns hearse in Springfield, Illinois. On April 21, 1865, Lincolns funeral train left Washington, D.C., on its 1,654-mile journey, traveling through 180 cities and 7 states, to Springfield, Illinois, where Lincoln would be buried on May 4. But the presidents burial wouldnt end the funeral trains travel. Each year the train, its mournful whistle sounding, journeys again along the same route, the casket still guarded by ghostly Union soldiers. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Before the Civil War, the Great Lake states had many trails to freedom for African Americans escaping slavery. It was a perilous journey, as slave hunters offering large bounties for the return of property pursued them, and laws made those who helped slaves subject to harsh fines, loss of property, and even imprisonment. But freedom overrode all concerns and slaves ran away, crossing into Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin on to Canada, where slavery was illegal; these concerns also didnt stop those helpers who believed in a higher cause than manmade lawsbe it attributed to a higher being or their own conscience and sense of justice.

One of the most haunted Civil War cemeteries, the Confederate Stockade Cemetery is located on the three-hundred-acre Johnsons Island in Lake Erie, near Sandusky, Ohio. A prison that housed approximately fifteen thousand Confederate soldiers was on Johnsons Island. The ghosts of many, including the two hundred buried there, engage in phantom battles and march along with the living during Memorial Day parades. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In 1831, Tice Davids, a slave from Maysville, Kentucky, swam across the Ohio River to the free state of Ohio. His owner, following closely behind in a skiff, came ashore shortly after Davids did. But the slave had already disappeared and all those whom the slave owner questioned denied having seen Davids.

He must have gone on some underground road, the slave master said, and thus the Underground Railroad, or, for short, UGRR, came to mean the complex spiderlike system of trails African Americans followed as they made their way north.

Though they look like the ghostly remains of stunted trees, these structures are really chimneys for the rathskeller at McCourtie Park in Somerset, Michigan, a stop on the Underground Railroad. Photo courtesy of Jane Simon Ammeson.

Stationmasters oversaw the depots which were homes and businesses offering shelter, a place to rest and eat; stockholders contributed money and goods; and the conductors helped fugitives move from one station to the next.

Together these people were the counterforce to slave owners and the institution of slaverymen and women not interested in money but in justice. And what they achieved is legendary.

With two children dead and buried, the thought of her last remaining child being sold into slavery made Eliza Harris determined, no matter the danger, to make her way from Kentucky to Canada and freedom. And so, late one night, Harris bundled up her two-year-old daughter and crossed the winter landscape to the shores of the Ohio River.

Her plan was to walk across the frozen waters, but a thaw had turned the solid ice into chunks. When the weather didnt change and with her pursuers getting closer, Harris took the risk, wading into the freezing water, climbing on and off ice floes drifting along the wide river until she miraculously found her way to Indiana soil.

The former home of Nathaniel Hanson, owner of Alton Machine Shop & Foundry and a fierce abolitionist, has passageways and rooms fifteen feet below street level, providing shelter for runaways. The building later became the Enos Sanitarium, and now, crowded with ghosts, it is the Enos Apartments, often included on tours of Haunted Alton. Photo courtesy of Alton Regional Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Harriss journey was far from over. Because of the success of the Underground Railroad, the Fugitive Acts were broadened in 1850, and anyone assisting or helping hide fugitive slaves could be sent to prison and fined $1,000almost $50,000 in todays currency. Slave hunters also were allowed to come north into free states and capture runaways; it was bounty hunting with huge financial rewards.

Next page

OF THE

OF THE