To the memory of my parents.

If I possess a single redeeming quality as a human being, it is the result of their example and tutelage. RIP.

And to Marjorie, who has endured so much, often, without my support. Unstinting in turn in her support and encouragement for this project, Thank you is inadequate.

I am indebted to the following, for their varying levels of assistance during the writing of the book.

First and foremost, my cousin, George Gallacher, who proofread the original manuscript and offered such sage and perceptive advice. A founding member of the iconic Scottish band, The Poets, he is nonpareil the best rock, pop and soul vocalist weve produced.

George Thomson, Geographics, Glasgow, for sourcing the in to my publisher Black & White, and also for printing the original manuscript.

Macca for his IT advice, when I feared Id lost half of the original manuscript.

Kenny Macleod, for advising me to completely redraft a chapter (and being right).

This book has not been ghostwritten. These are my words and, consequently, interpretations of situations and opinions of people are mine alone. Dealings with informants happened as I have described, but in order to ensure their continued safety, I have disguised their identities.

CONTENTS

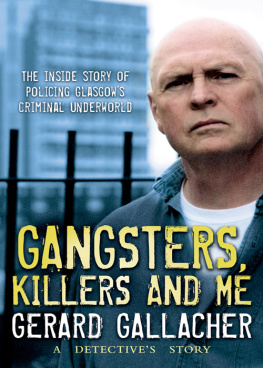

This book covers my time as a police officer (primarily as a detective) in Glasgow during the 1980s, 1990s and the start of the new millennium, when drugs took hold of the city (and never relinquished their grip). Many of the robberies, murders and deaths in this book stem from the drugs trade, but many dont and owe their origins to the culture of violence that is endemic to Glasgow. You cant live any time in the city without becoming either a passive or active victim of that violence.

I had experience of the violence well before I joined the police. Id witnessed it as an innocent fifteen-year-old coming home from football training in Govan. I was on the top deck of a bus and it stopped outside a pub and below me on the street, I could see a man and woman arguing. The man, with no warning, headbutted the woman full in the face and she fell prostrate to the pavement, blood pouring from nose and eyebrow.

It both horrified and shocked me. Id been in plenty of fights of my own, typical young boy scrapes, but Id never seen a woman struck before. I got home and relayed the story to my parents. Both had been brought up in the rough Garngad district of the city and no doubt had seen all that and more. Their response was, Thats drink and life in Glasgow, son.

About a year later, I narrowly avoided becoming another victim of the youth gang violence that was rampant in Glasgow during my formative years. That I escaped was due solely to being fleet of foot. Walking home from public swimming baths in Springburn, I was asked by a group gathered in a close where I was from. When I stupidly gave the name of my scheme and it wasnt Springburn, I heard the words chib him; Glasgow parlance for slash. I didnt hesitate before taking to my heels. I can vouch for the phrase fear lends wings.

A lad who played casual football with a group of us every night of the week didnt have my blessed fortune. A quieter, more decent lad you couldnt find, but he was savagely and randomly murdered. One Friday night, returning from a Partick Thistle supporters meeting, he stepped off a bus in Barmulloch, 100 yards from his house. Near the bus stop was a gang from a nearby area on the rampage. He was the first boy they encountered and they bludgeoned him to death.

Dear green place is how Mungo, the Christian saint credited with discovering Glasgow, allegedly described it, but somehow, through the centuries following its founding, the dear green on the traffic lights jumped to blood red and skipped the amber.

Glasgow has achieved worldwide prominence for shipbuilding, contributions to medicine, science and architecture, but also football rivalry and savage violence often intertwined.

The innovation and beauty of the architecture can leave you breathless but there is no beauty attached to the violence, only stark ugliness that so often takes the breath away from the victim permanently. Glasgow didnt invent violence but many of the citizens seem determined to prove theyve perfected the art.

The violence requires little or nothing to set it off: territory; religion; football rivalry; drugs; a misplaced look at a wife or girlfriend; or simply a misplaced look. You could be a victim purely because you had facial features someone disliked.

Tempers as unstable as gelignite combined with unquenchable alcohol consumption produces a volatile cocktail. The weapons are whatever is readily available, which tends to be anything bladed: knives; razors; swords; meat cleavers; axes weapons hardly different from those wielded in 1314 at Bannockburn, and every bit as deadly.

In the 1980s, the use of firearms in Glasgow violence increased owing to the availability of stockpiled Eastern Bloc guns, but they tended to be the remit of gangsters. For the most part, the citys victims are stabbed, slashed, chopped and diced. The forces of law and order, the police (or in Glasgow the polis), have been tasked with, at best, combatting the tide of violence or, at worst, trying to stem the (blood) flow.

Glasgow back in the 1930s had the razor gangs, so-called because of their use of open or cut-throat razors to slash the faces of their victims. With no plastic surgery specialists available, the legacy of the facial wound was a raised, jagged and ugly scar. Doctors stitching the wound sometimes asked the victim if they knew their assailant and were told, Yeah and Ill send him in for you to do the same job next week. And invariably, they did.

Sir Percy Sillitoe, who would eventually head MI5, was Chief Constable of Glasgow at the time and was credited with smashing those rampaging gangs. His officers were instructed to meet violence with violence and through split heads and long jail sentences, leave gang members in no doubt that their time was over.

The 1960s and 70s brought a resurgence in gangs and similar police tactics. Membership and territory were everything. Battles raged nightly in the various housing estates, pubs and dance halls in Glasgow city centre. Pubs like the Lunar Seven, which sat at the junction of Buchanan Street and Bath Street, were the scenes of murder and mayhem every second weekend.

The police response? The formation of a group nicknamed The Untouchables, simply because they appeared to operate outwith the confines of natural justice. They were hard-nosed men, who drove around team-handed in vans, with blacked-out windows and a similar remit to their 1930s predecessors.

It was iron-fisted policing in an iron glove, although its success owed much to a sympathetic judicial system. Sentences of ten and fifteen years for serious assault, attempted murder and mobbing and rioting quickly concentrated the minds of the sixteen- to twenty-year-olds responsible for the violence.

From the 1980s onwards, the focus of the violence was often created by those earning vast illegal profits, who dictated what was sold in the city and where. I joined the police in 1981 and was to witness the city at its worst over the next few decades.

Brothers trying to murder brothers; a drug courier double-crossed and murdered for his consignment; a newborn baby thrown into a canal and left for dead; prison riots; a father trying to murder his children before attempting suicide; mafia-style revenge killings; the slaughter of a Procurator Fiscal; the rape of a foreign national; and among all that, I would find myself falsely accused of being responsible for a murder and distributing drugs.

What a birthplace. What a profession to choose.

No mean city? Too damn right!

September 1995, late afternoon, and I was standing in a bin-shed area in a lane that ran behind a pharmacists shop in Saracen Street, Possilpark.

Next page