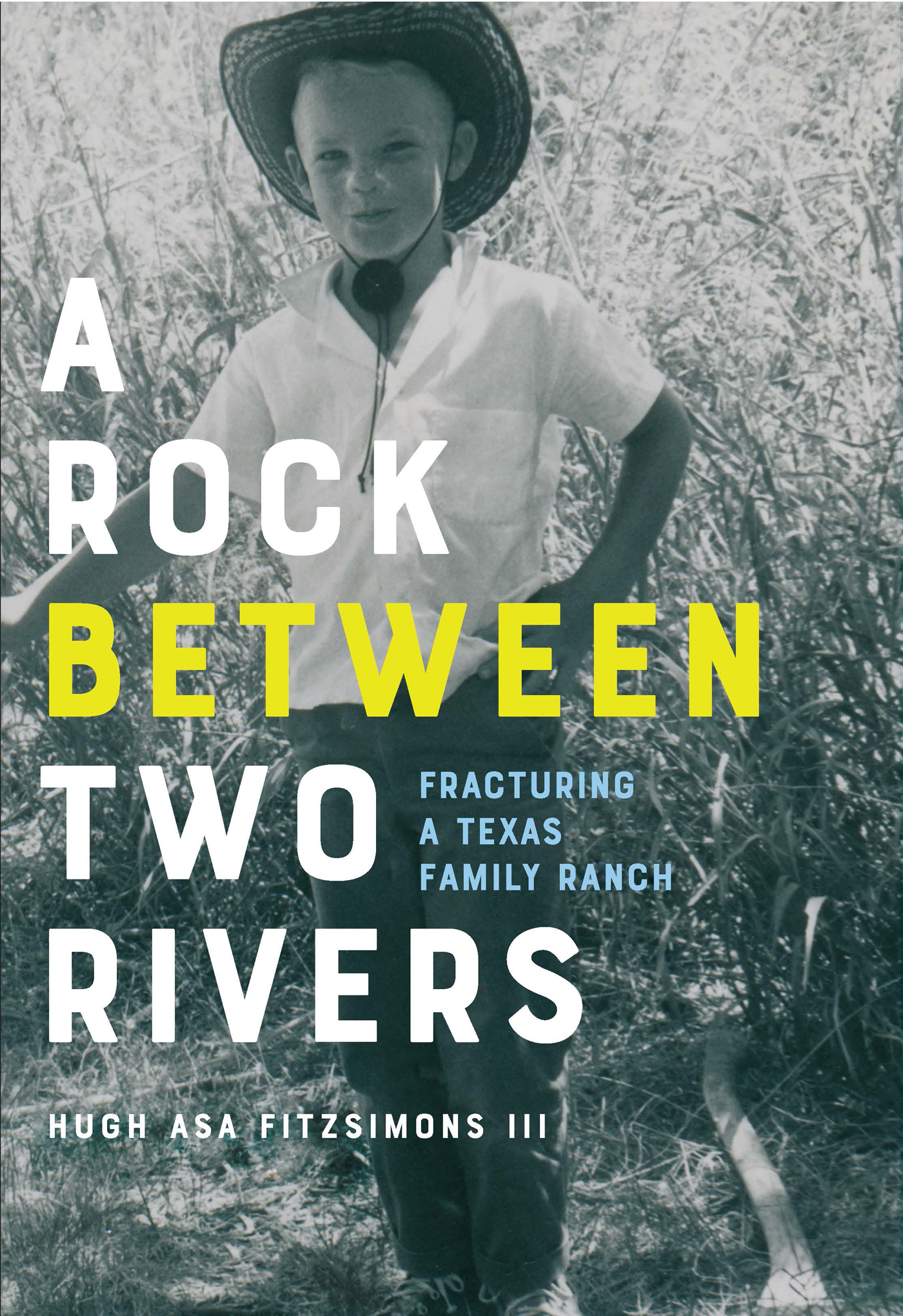

A Rock

between

Two Rivers

Fracturing a Texas Family Ranch

HUGH ASA FITZSIMONS III

Trinity University Press

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2018 by Hugh Asa Fitzsimons III

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Jacket design by Rebecca Lown

Book design by BookMatters, Berkeley

Author photo by Joanne Herrera

ISBN 978-1-59534-840-1 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-59534-841-8 ebook

Portions of this work appear in a different form in TribTalk.org (A Rancher on the Border of Fear and Compasion, August 3, 2014) and in The Politics of Hope: Grassroots Organizing, Environmental Justice, and Social Change, edited by Jeffrey Crane and Char Miller (University of Colorado Press, forthcoming).

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

Printed in Canada

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi 39.481992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

222120191854321

For Sarah

I may not know who I am, but I know where I am from.

WALLACE STEGNER

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The South Texas land we call the despobladothe wild horse desert, the land whose union with the submersible water pump blossomed into the Wintergardenhas a history that runs deep. This land is every bit as fragile as it is resilient. Its hardened exterior makes itself known when push comes to shove, or overgrazed bare, or plowed up for us to extract more than it was ever intended to produce.

The first white men to arrive in this country found flowing creeks and artesian springs that must have set their minds in motion. Surface water in a land of periodic drought and desiccation was surely a resource they could use to further their lofty ambitions involving land and livestock. And thats exactly what they did. In his 1812 petition to King Ferdinand of Spain, Juan Francisco Lombrao described his desired land grant as being so fertile that it was home to thousands of sheep, horses, mules, donkeys, and cows. He christened his land grant Las Isletas after the tiny islands in the nearby Rio Grande. A mans wealth, after all, was measured by the number of animals he could claim.

I wonder what Lombrao thought when he gazed at this horizon. He must have imagined an endless supply of pastureland for his animals to graze. Resting his eyes on the nearby Rio Bravo and beyond, he saw only the prospects of land, water, and wealth. He could not foresee the years of little rain, the overgrazing, and the ruin of trying to extract too much from a land that has its limits.

By the 1880s South Texas had over 3.5 million sheep, a number that decimated the available forage and ushered in the destruction of rangelands, some of which bear those scars to this day. The once-lush grasslands fought back with thorn, mesquite, and prickly pear, cultivating a land inhospitable if not downright dangerous to trespassers. One run-in with a tasajillo cactus drives the point home. Their barbs implant in your skin and cause more damage by claiming a sizable chunk of your flesh when you work up the courage to yank them out with a pair of pliers. Leave me alone, snarls the land.

No one imagined the consequences of the first oil exploration in the 1920sthe scale and magnitude required for this manner of extraction, as well as its reward. Weve had real and imagined oil booms ever since. Some have resulted in lawsuits and bankruptcy, and others have produced vast sums of wealth for a privileged few. Regardless of the outcome, it all boils down to water and its concomitant by-products, contamination, and depletion. Its a story both ageless and potentially lethal.

In the eastern and northern quadrant of Dimmit County, where the Nueces River recharges the Carrizo sandstone, the aquifer has managed to sustain itself. Starry-eyed immigrants hailing from lands much more verdant than the county planted everything from figs to strawberries; vast citrus orchards and rows of date palms graced the burgeoning settlements of Valley Wells, Brundage, and Bermuda. The township of Catarina boasted a high school, a country club, and a railroad spur. The area was known far and wide as the Wintergarden. Come to Dimmit County, said the booster. Its a poor mans heaven. And it was, before the water table dropped and the expense of pumping made farming impossible.

Today this land is better known as the Maverick Basin, forming the westernmost extension of the Eagle Ford shale. Its major output of both oil and natural gas make the Eagle Ford the most rapidly developed shale play on the planet.

From the highest hill on my ranch, you can see the mountains of Mexico. On a clear day the faint jagged outline of the Sierra del Burros frames the horizon to the south and west. Its a sight that evokes what mountains have always stirred in people who gaze at them from afar: the subtle suggestion of hope. At twilight when the sun drops below, their silhouette expands, and so do you. It fills you with a love of where you are.

As the sky darkens other lights appear. Orange and yellow flames, miles in the distance, dot the boundaries of the view: a half-dozen roaring exclamation points of energy unleashed, natural gas flares that burn with an intensity no simple fire could ever match, hydrocarbons the earth has compressed and held for 500 million years. They are the product of our time, the wasted refuse of our unrequited quest for more. They are the visual, physical, and emotional reminder of where this land is headed.

ONE

The First Days of Oil

It begins with my grandfather, a man I never knew. A faded black-and-white photograph of him hanging on the wall of my office at the ranch shows him sitting astride a large gray dappled horse that looks both old and steady. My grandfather is watching a blacksmith hammer a piece of iron, not to shoe the horse but to make a part for a cable-tool drilling rig. A horseman at heart, he stands at the dawn of the petrochemical-industrial age, a pioneer.

My grandfather was born in the hamlet of Thompsonville, Texas, a wide spot in the road just west of Gonzalez on old US Highway 90. He was educated in a one-room schoolhouse outside of town until the eighth grade. His father, James Sword Fitzsimons, was a dreamer and a drifter, having moved from Louisiana after the family had lost everything during the Civil War. As an amateur fiddler on the local vaudeville circuit, he was not much for providing financial security, and my grandfather had to drop out of school to help support the family when he was twelve. The next year, he saddled up and became a cowboy for hire.

Next page