University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

Copyright 2009 by Linda Hussa

Photographs copyright 2009 by Madeleine Graham Blake

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Design by Kathleen Szawiola

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hussa, Linda.

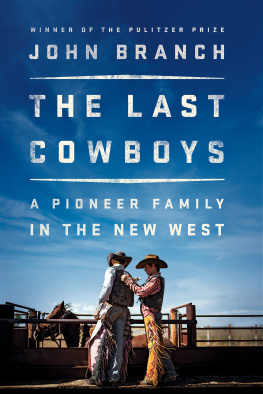

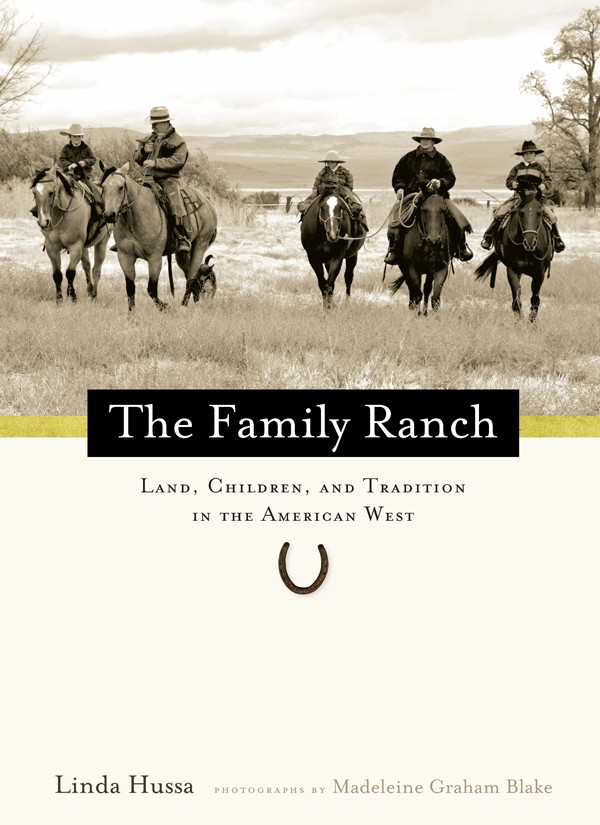

The family ranch : land, children, and tradition in the American West / text by Linda Hussa ; photographs by Madeleine Graham Blake. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87417-771-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Ranch lifeWest (U.S.) 2. RanchersWest (U.S.) 3. FamilyWest (U.S.) I. Blake, Madeleine Graham, 1948 II. Title.

F596.H88 2009

306.850978'091734dc22

2008043554

Credit: Anthem by Buck Ramsey is from Buck Ramseys Grass: With Essays on His Life and Work. 2005 Scott Braucher and Bette Ramsey, Texas Tech University Press, 800-832-4042. Reprinted with permission.

Frontispiece: Visalia and Charley Hammond

ISBN-13: 978-0-87417-819-7 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-87417-781-7 (ebook)

Preface

When youve reached the edge of an abyss, the only progressive move you can make is to turn around and step forward.

ANONYMOUS

This book is about ranch families in the rural West today. Remarkable stories arise when these parents, their children, ranch work, and nature come together for a lifetime. Modern America offers few other situations where the family enterprise continues to thrive as it does on ranches like these. Entire families work together for the success of the common enterprise. Parenting includes passing on to the children the skills, values, and traditions that have held the ranching community togetherin every state, in every region, in every countryfor generations, because they work.

The book is also about the challenges of maintaining the family ranch as viable and the ways independent ranchers meet those challenges. Although ranching protocol has not changed over time, ranching in the modern world has gotten a great deal more complex. Regulations governing grazing and water rights, taxes, and inheritance laws, as well as the challenge of providing education for children on ranches that may be a hundred miles or more from the nearest school, escalating operational costs, and markets that respond more to international politics than local supply and demand threaten their unique way of life.

I know of no other industry that turns totally within the concentric circles of family and community. Company towns build up around mining and timber sites, but none immerse the whole family, including children, in the day-in, day-out, year-round work like ranching. Even their clothing, developed for out-of-doors rough use in winter or summer, is a signature look.

Films, documentaries, and the media tend to emphasize stereotypes when depicting people of the land. In order to find unique yet authentic families, I polled ranchers, cattle buyers, and farm advisors around the Great Basin, and talked with the staff at the Western Folklife Center. Their list of recommendations was astounding. The families Ive chosen to focus on represent scores of others who etch their presence on the land in clear terms. They are as different as wildflowers: the members of four of the families are biologically related, while those of two others are linked by adoption; one is a single mom, and one is a single father. Yet they all accept the challenge of tending and growing a small business, despite the odds, and in doing so they bring their children along. I wish all of those recommended could have been included. In spirit and commitment, they are here. Any generalization made on these pages is based on a personal perspective shaped over a lifetime of working and playing with ranching families, and I hope it will be taken in that spirit.

PARENTS IN THE WEST make use of tools present in the physical world outside the classroom: Going out on horseback replaces recess; learning where to be to turn the wild cow is companion to splitting fractions; assessing the feed and the condition of the cattle is economics; helping with irrigation is mathematics, geology, understanding contours of the land, and the exercise of practical application; sending a loop to settle swiftly on a calf at a branding is the finesse and teamwork of sports; the responsibility of caring for animalsseeing birth, trying to hold off deathare undertakings of a serious nature. All of these lessons build self-esteem.

These parents nurture and care for their children with tenderness, marveling, forgiveness, compassion, and trust, making sacrifices to give them a life in and with nature. Within that context they encourage their childrens thinking outside the self by connecting them to the welfare of animals, land, water, and the community of neighbors. Carrying thought forward to action requires planning beyond self, contributing to their development as responsible, productive citizensthe very qualities of a leader.

Indeed, this book shows, above all, that the children of ranching families have time and space and silence in which to explore and grow their own ideas, to figure out how things work. Combined with their practical experience, they develop common sense, good judgment, and independent thinking. At home, there may be a school set up in an extra room, or a studio with modeling clay and colored pencils, or a shop with a plasma welder and a pile of banded pipe. Children range in age from infants to college-age young adults. The thing they have in common is a right to a sane and caring future.

THIS BOOK began in 2004 when I heard the story of Joyce and Joe McKay, ranchers in eastern Oregon, who had adopted six Haitian children from halfway around the world. In doing so they reached across lines not commonly crossed in the rural West.

In the heart of conservative ranch country, Joyce McKay grew up in a house where black faces were daily companions. Her father, Julian Arrien, subscribed to Ebony magazine and, among other newspapers and magazines, he set Ebony out for his children to read. It may have been an unusual choice for an immigrant Basque sheepman, but Julian kept an open door to new people and ideas.

Joe McKay and his brothers and sisters shared their space and the food on the table with displaced kids from the area. Joes parents willingly took in any orphaned or left-behind child. The McKay home nearly levitated with the thump of energy generated by their generosity.

When Joyce and Joe married, this generosity and openness became a part of their union.

When an article featuring the McKay familyand their adoption and rearing of six Haitian children on their ranchran in the Western Horseman magazine, reader response was unprecedented. The public wanted to know more about working ranch families. That launched the idea for this book.

As luck would have it, a second extraordinary ranching family, the Stoddarts, moved to our ranch. They had three children at that time, with a fourth born a year later. These children were on horseback with their mother, Tami, from the age of two weeks.

Joyce was handed the world in print by her father. Tami had a mentor, too. Her grandmother Marge Isaacs passed away long before Tami was born. On a trip home, Tamis father gave her the journals and papers of her Grandmother Isaacs. One of her journals contains a letter written forty-five years ago to the president of