| Copyright 1986 By Abel G. Rubio Published By Eakin Press An Imprint of Wild Horse Media Group P.O. Box 331779 Fort Worth, Texas 76163 1-817-344-7036 www.EakinPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68179-198-2 PB ISBN: 978-1-68179-133-3 HB ISBN: 978-1-68179-135-7 |

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a newspaper or magazine.

Library of Congress Ctaloging-in-publcation Data

Rubio, Abel G,

Stolen Heritage

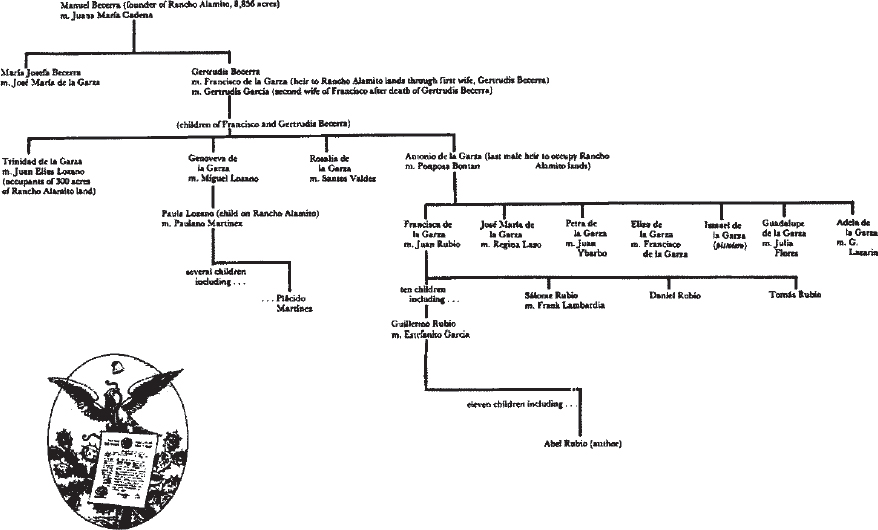

1. Mexicans Texas. 2. Becerra family. 3.Land grants Texas. 4. Garza family. I. Title.

F395.M5R8 1986 929.20973 85-32070

ISBN 978-1-68179-133-3

Cover art and illustrations by Jack Jackson

To the memory of two of my cherished ancestors, great-grandfather Antonio de la Garza, Refugio County, Texas, cattleman of the 1860s and 1870s, and his beloved wife, my great-grandmother, Ponposa Bontan, for being ultimately responsible for my seeing the light of day; and for having been so grievously wronged.

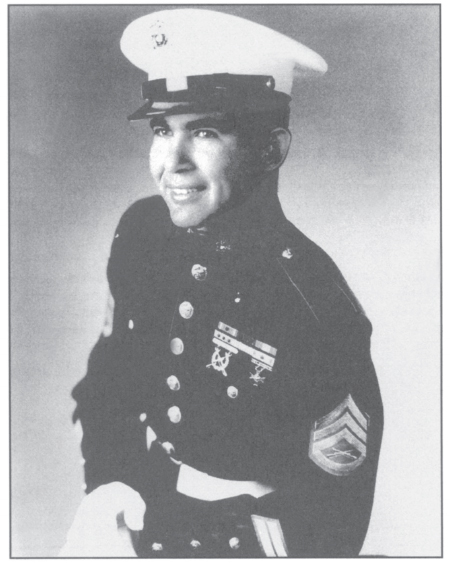

The author as a young Marine.

Foreword

I have often wished that the Mexicans, or some one who had their confidence, could have gone among them and got their stories of the raids and counter raids [in South Texas]. I am sure that these stories would take on a different color and tone.

Walter Prescott Webb, January 1963, two months before his death

In the development of the United States from the late eighteenth century until the early twentieth century with its urbanization, sophistication of labor and industry, and rise of the professions, land ownership was fundamental to personal wealth, status, and power. Owning or controlling land was an essential factor in determining an individuals place in society. Moreover, it was central to the vision of opportunity and expectation. The desire for land ownership primarily motivated frontier westward expansion, the core of the American experience. Much of American character and its world view has been configured by the continual quest for land from the Cumberland Gap to the Pacific Ocean. When, in 1890, the Bureau of the Census officially declared that a frontier no longer existed within the continental United States, the news created a mental crisis that was discussed in the highest intellectual circles of the nation. Even the most urban-dwelling American still defines his position in society partly in terms of land possession, mainly in the form of home ownership.

Nothing was more important to an individuals place in Texas society during the nineteenth century than land, either for agricultural pursuits or for speculation. It formed the basis of most individual empires and underscored personal security for a family and its descendants.

Central to the vision of opportunity which brought the first non-Hispanic settlers to Texas in the early 1820s was the promise of owning land. The Spanish and then the Mexican governments promises of land to the individual, through empresarios, swelled the population of Texas from the original Old Three Hundred of Stephen F. Austin to over 30,000 by the eve of the Texas Revolution. Texas in the 1820s and 1830s was a large and virtually unoccupied territory. Most Texas lands were open, and the settlers had much to choose from. Only the Indian stood in the way of settlement, and this barrier, formidable though it was, receded decade by decade until only an obscure handful of red men remained on Texas soil. The majority were either exterminated or removed to regions outside the borders. Chief Bowles and his Cherokees and their affiliate tribes along the Angelina and Neches Rivers in East Texas serve as perhaps the most startling example of land dispossession in early Texas history. Bowles and his people claimed thousands of acres of rich farming ground. During the Texas Republic, however, these Indians were systematically and brutally driven from their homes north across the Red River by government forces so that the region could be utilized by mainstream Texan society.

Although the Indians gave way to the new order of things, there were other people occupying coveted land in Texas prior to Anglo usurpation. A century of Hispanic claim to Tejas left a residue of settlement in places as far east as Nacogdoches and as far west as El Paso del Norte. Most of the several thousand Hispanics in Texas, who can be referred to as Tejanos, lived in the southern and southwestern regions. Their northeastern border included the line from Refugio to Goliad and San Antonio. In these villages and their outlying regions, there existed an indigenous ranchero culture that had done its share to neutralize its predecessors, the Indians. There was little in Texas to lure the Hispanic north of the Rio Grande in those years, and the population remained relatively small though secure on land grants from the Spanish and Mexican governments.

The Tejano population was veritably inundated by Anglo immigration after 1821. By the end of the Texas Republic, if not earlier, the Tejanos, as a group, had lost the economic, social, and political prominence they had once possessed. By the end of the nineteenth century, ownership of the land, even in South Texas, changed from Spanish surnames to the non-Hispanic newcomers. Land was the object of desire in the territory south and southwest of the Refugio-Goliad-San Antonio line just as it was in the rest of United States development.

While the vast majority of the present Hispanic population in Texas originated with the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and the resultant immigration northward, there is still a relatively small but viable group of residents who can claim direct descent from this pre-1820 Tejano population. They can rightfully claim to be the first non-Indian culture in the state. Especially strong among these Tejano descendants is the traditional view of land dispossession of the nineteenth-century Texas Mexicans a view that, in its generalities, remains in the standard histories on the subject. That view holds that with the inundation of Texas by non-Hispanic immigrants, especially from the United States and numbering around 100,000 people by 1846, life was never again the same for the Tejanos. After the region changed hands in 1836 and again in 1846 with annexation by the United States, the