Contents

THE OVERCOAT WAS BEFORE ME AT LAST.

Beauty is always strange.

C HARLES B AUDELAIRE

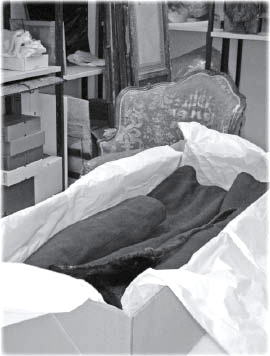

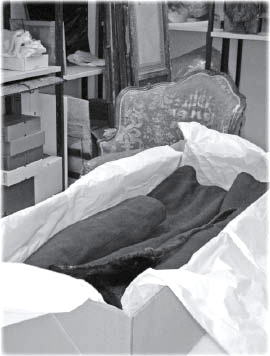

I stood in that big room with the fluorescent lighting, like someone who had come to identify the body of a loved one. M. Bruson and his assistant brought out a cardboard box. They carried it delicately and with a certain detachment, as if exhuming such a meager thing were beneath them. They placed the box on a metal-topped table in the center of the room and removed its cover. All of a sudden the men, shaking out sheets of tissue paper, their arms raised, were covered in white, like two gesticulating ghosts. I was immediately overcome by the smell of camphor and mothballs.

I approached the table slowly, taking little steps, smiling with embarrassment. The overcoat was before me at last, laid out like a shroud at the bottom of the box on a large sheet of tissue paper. Stiffened by paper padding, the coat seemed to be covering something dead. Tufts of tissue were protruding from the heavily padded sleeves. I bent forward farther. It struck me that inside the box was a dummy, a plump, corpulent, barrel-chested dummy with no head or hands.

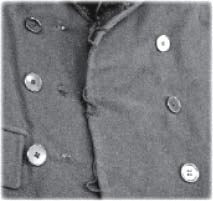

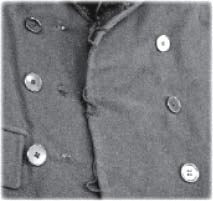

I was uncomfortable in the presence of M. Bruson. He discreetly sought not to fix his gaze upon me, but I knew that he was spying on me surreptitiously. Unable to resist, I lightly fingered the overcoats threadbare, dark gray wool, worn smooth at the hem. It was a double-breasted coat, closed by two rows of three buttons. At some point these buttons had been moved to alter the coat for someone thinner, yet traces of where they had originally been sewn on remained visible, little buds of black thread. A small hole in the cloth suggested a missing button that must have been used to close the collar. From the black fur lapel hung a white tag, tied to a red string. I lifted it up, but there was nothing written on it. I unbuttoned the coat in hopes of finding some clue, a label indicating the name of a store or tailor: nothing.

Hopeful, I slid my hands into the pockets: again, nothing. The overcoat was lined on the inside with otter, the fur worn thin and devoured by mites. M. Bruson seemed impatient, but I wasnt quite ready to detach myself from this inert, sham figure. I decided not to leave just yet. Really, hardly several minutes had passed, and this was the overcoat Proust had wrapped about himself for years, which he spread upon himself like a blanket while in bed writing In Search of Lost Time . The spirit invoked in Marthe Bibescos memoir came back to me: At the ball, Marcel Proust sat down in front of me on a little gilded chair, as if coming out of a dream, with his fur-lined cloak, his face full of sadness, and his night-seeing eyes.

I thanked M. Bruson. Carefully, he made several small readjustments: he plumped up the paper padding, rebuttoned the coat, and buried it again under its blanket of white tissue paper. He fitted on its cardboard cover. With the help of his assistant, the box was lifted and placed back up on the highest shelf of a metal storage unit. Before leaving, I took one last look behind me. On the side of the box, in capital letters, a black felt-tip pen had been used to inscribe prousts overcoat . I went out, across the beautiful interior courtyard of the Muse Carnavalet, and left by the same side door through which I had entered, onto rue de Svign.

It all started when I interviewed Piero Tosi for a television program. Tosi is the celebrated costume designer who worked side by side on many remarkable projects with Luchino Visconti, the esteemed Italian film and theater director. That afternoon, at Tosis house near the Piazza Navona in Rome, he spoke with me about his life and some of his extraordinary experiences. As we were finishing up, though the hour was late, I couldnt resist the temptation to ask him about Proust. I knew that in the early sixties, Tosi had been delegated by Visconti to oversee plans for shooting a film adaptation of In Search of Lost Time in Paris, plans that were soon abandoned.

Tosi, though reserved, began to elaborate in great detail: We were so enthusiastic, so hopeful about finally bringing this project to life. Luchino had already made contact with some of the biggest names in world cinema. We were talking to Laurence Olivier, Dustin Hoffman, certainly Greta Garbo, actors of international renown whose names would help finance the film. But personally, I was a bit hesitant. Lila de Nobili, a great costume designer I revere, had said to me: Its not possible. To make a film based on Proust is absolutely impossible. The cinema is something concrete. You cant transpose memory into film. But Visconti was determined, and sent me to Paris to oversee the project and begin the research. I met Prousts niece, Suzy Mante-Proust, and several aristocrats who had known the models that inspired certain of the characters, such as the Duchesse de Guermantes and Baron de Charlus. I spent a lot of time speaking with them, but they had nothing I could really use. Then, one day, someone mentioned a gentleman whose name I have forgotten.... I know I still have his calling card somewhere, because I never threw it away. I was told that he was a collector of Prousts manuscripts and that he might be very helpful.

Tosi tracked the gentleman down, requested an appointment, and went to meet him. It wasnt a simple trip, going out and finding an office in the suburbs of Paris. Finally, Tosi arrived at sunset in front of the gates. I remember, he told me, a brick wall, a grove of horse chestnut trees, a factory. This gentleman was the owner of a business that manufactured perfumes. He received me in his office, a vast room with pink walls, lined with shelves laden with bars of soap. The scent of lavender and violet perfumed the air around me. As he sat behind his desk, the image I had of him was of a large nocturnal bird, black and fantastic. He spoke an old-fashioned Frenchmarvelous, sublime.

The man sitting behind the desk proceeded to tell Tosi the extraordinary story of how a growing passion for the writings of Marcel Proust had overlapped with a serious medical condition. One summer, as a young man in Paris, he suffered what seemed to be a bout of appendicitis. An eminent surgeon was summoned to operate on the young perfume magnate. Called back to Paris from his vacation in Vichy, the doctor was Robert Proust, the brother of Marcel. Some time after the operation, the patient paid a call on his doctor, who gave him the opportunity to see some of his legendary brothers manuscript notebooks. This experience left a profound impression on the young man, and he began to hunt for anything that had to do with the great writer. He made contact with the family, with relatives, with friends. He pored over obituary listings in Le Figaro , and when someone who had played a part in the Proustian world died, he would attend the funeral, worming his way into the church, pretending to be a relation. Singling out the one person at the gathering who most interested him, he would ingratiate himself, initiate a conversation, then pump the person for information.

Tosi listened, rapt. At the end of this unforgettable meeting, the man revealed to Tosi that he had once possessed Marcel Prousts bedroom furniture, which he eventually donated to the great museum of the history of Paris, the Muse Carnavalet. However, he further confided, he still owned the famous overcoat, the coat in which Marcel had swaddled himself while out on various adventures and escapades, the coat that doubled as a blanket when he wrote in bed at night.