Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

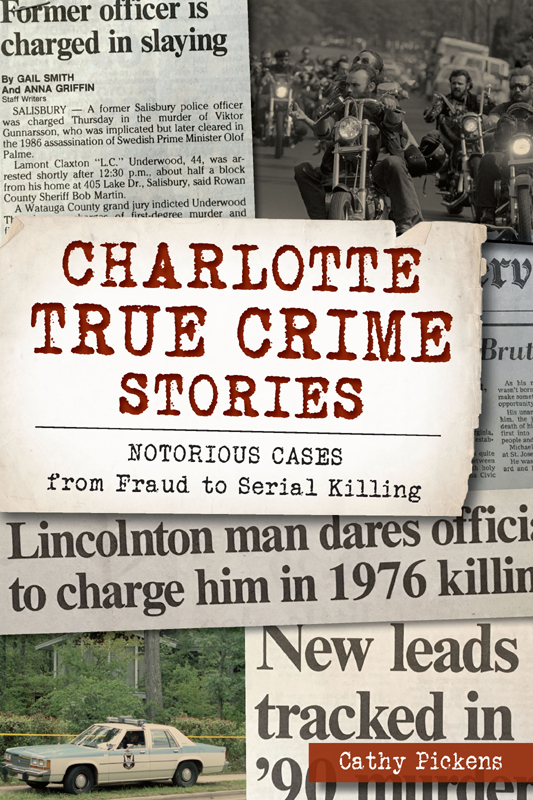

Copyright 2019 by Cathy Pickens

All rights reserved

E-Book year 2019

First published 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.766.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019939734

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.245.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Charlottethe Queen Cityand to her stories, her storytellers

and those who preserve them.

A Carolina country road. Photo by Wes Hicks on Unsplash.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

So many people have helped make this book:

* The amazing staff of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room and the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, particularly Shelia Bumgarner, the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room librarian. She is a strong advocate for protecting the visual and historical record of Charlottes history and making it available to those curious about the past.

* The writers and photographers who have covered Charlottes history and told its stories in newspapers, blogs, television news, documentaries, websites, books and other venues.

* Whats a writer without writer friends? Thanks to those who read this book in various stages and who continually encourage my projects: Daniel (Chipp) Bailey, happily retired from sheriff-ing; Paula Connolly, Ann Wicker, Dawn Cotter and Terry Hoover, all Really Mean Women; Allison Fetterman; John Jeter; Jeremy Bishop; the merry crew at Charlotte Lit; and Landis Wade and his Charlotte Readers Podcast.

* The team at The History Press who made this project happen, especially editors Kate Jenkins and Sara Miller.

* And always, my husband, Bob; my sisters; and my dad.

THE HORNETS NEST

STATISTICS OR STORIES?

Charlotte has always kept an eye on its place on the national stage while, at the same time, maintaining its sense of humor. Typically, civic leaders only talk about crime in its absence, but in a 1940 Charlotte News editorial, the writer took the FBIand J. Edgar Hoover, personallyto task for snubbing Charlotte and robbing it of its honors as the nations murder capital, beating out Atlanta (its ancient rival for first honors).

As we recall it, pointed out the editorial writer, with tongue poked into his cheek, the town was at least seven times as murderous as Chicago and ten times as murderous as New York. Yet the annual FBI crime statistics reported that year gave neither hide nor hair of mention of Charlotte. We couldnt believe our eyes.

Putting the blame firmly on Hoovers desk, the editor wrote, The man not only has no feeling for the proper pride of a city, he has no sense of drama, either.

Charlotte has always enjoyed a proper pride and a dash of drama. The region has historically been a safe, pleasant place to live but has had its moments in the national crime spotlight and was once dubbed Little Chicago in a 1961 Charlotte News headline.

By 1966, Charlotte had achieved the ultimate crime-status pinnacle: number one in the nation in murders per 100,000 residents, with almost three times the national average. That year, Charlotte had thirty-seven homicides; to compare, there were eighty-seven in 2017Charlottes seventh-deadliest year. Twenty years earlier, Charlotte had been number two in the national murdering ranks.

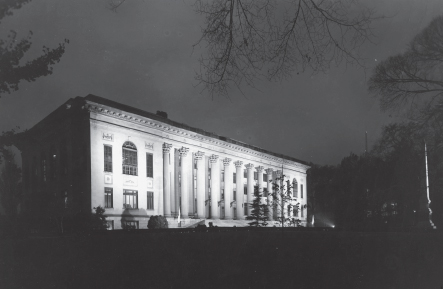

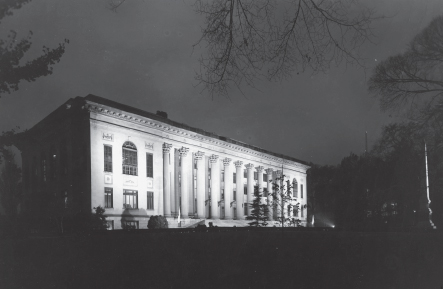

Mecklenburg Countys fifth courthouse (in operation from 1928 to 1978), located at 610 East Trade Street, was in use when the citys murder rate hit number one in the nation. Courtesy of Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Statisticsgood ones and bad onesfluctuate over time, and not always with clear reasons for the ways people can go wrong. Comparison statistics seldom give a clear answer as to whether were safe or what causes spikes and lulls in crime. Still, we look for explanations and rationales.

In 1977, the police compiled Charlottes crime data to create an average murderer: A man who uses a pistol and kills somebody he knows during an argument at a residence between 10 and 11 on Saturday night. That description summarizes, with fair accuracy, more recent crime statistics; so, while it may seem like things change, they really dont.

Those regularly reported annual statistics or average stories seldom grab headlinesor imaginationsfor long. So, what makes a story become part of the warp and weft woven into the essence of a city and the people who call it home?

These are the Charlotte stories that started in dark places but show the heart of a city that is still southern and, in good ways, a bit like a small town. These are Charlottes headline crimesthe stories too important to forget.

THE ORIGINAL NEST

Charlotte started as a crossroads. The areas first public building, erected in 1766before Charlotte became a town in 1768was a courthouse, encouraging others to recognize the settlements respect for law and order, its centrality and its sensibility, though it had fewer than twenty houses.

Soon after, in the Revolutionary War, family and friends faced each other in the Carolinas, where comparatively few British regular troops were stationed. Fleeing losses in Charleston and Camden, British general Lord Cornwallis overtook the Continentals in the Waxhaws (now Lancaster County) just south of Charlotte.

In 1780, the Battle of the Waxhaws (or Bufords Massacre, depending on which side was telling the story) took place forty miles south of the crossroads. The Patriots surrendered. How it turned into a bloody massacre was open to dispute. Banastre Tarleton, the British officer in command, lay pinned under his horse and reportedly had nothing to do with the order to shoot. The Patriots had a different story. The cairn where 150 Continental soldiers were buried stands outside Lancaster in the Buford community named for Virginia officer Abraham Buford. After that skirmish, remember Tarletons quarter came to mean take no prisoners. The locals were riled.

Four months later, Cornwallis took Charlotte. Charlottes residents were none too happy with the occupation forces, especially as news of the massacre spread. Local antipathy turned into acts of sabotage, and Cornwallis reportedly wrote that Charlotte was a hornets nest of rebellion. Though Cornwalliss letter has not been found, and some count it as rumor, the description stuck.

Hornets nest patch used on Charlotte-Mecklenburg police officers uniforms.

Next page

![Charlotte Greig - Evil Serial Killers. In the Minds of Monsters [Fully Illustrated]](/uploads/posts/book/70143/thumbs/charlotte-greig-evil-serial-killers-in-the-minds.jpg)