This book is the end result of a long and fascinating research journey. For years I have been gathering everything I can get my hands on about the Montreal Laboratory and the people who worked there, unearthing information on over 400 of the Laboratorys employees in the process.

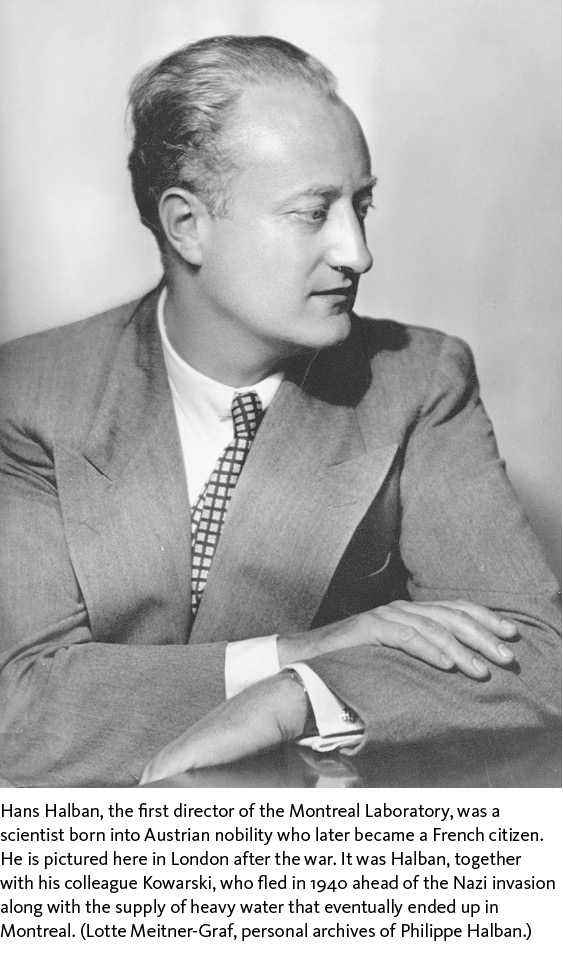

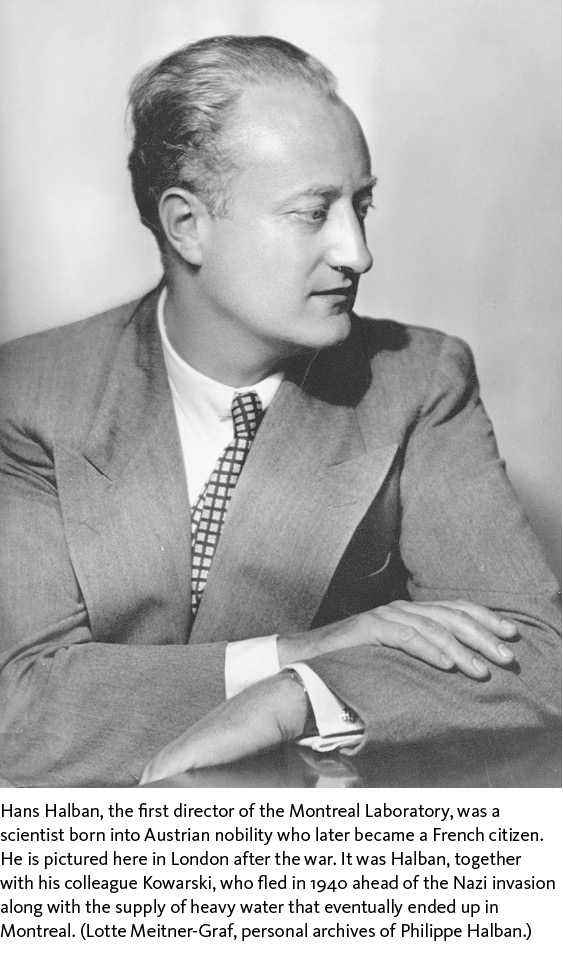

I managed to track down a handful of people still alive today who worked at the Montreal Laboratory during World War II. I also had the opportunity to meet and interview two of themchemist Alma Chackett and computer Joan Wilkie-Healand reached out to some thirty individuals whose parents once worked at the Montreal Laboratory. All of these people were extremely generous in sharing with me a huge quantity of documents and photos, as well as their memories about the day-to-day work at the Laboratory. The diary belonging to Hans Halban, the Laboratorys first director, which was graciously provided by his son Philippe Halban, was especially helpful.

I believe the fact I work in the nuclear sector as an engineer specializing in power plant safety has provided me an insiders perspective and the relevant knowledge to fully appreciate the work carried out in Montreal during the war.

I leaned heavily on both the British and Canadian national archives, both of which contain a wealth of information about the Montreal Laboratory. I read and drew from many of the 600 reports produced by the project during the war that are archived in Londons Kew Gardens and available in electronic format. The books listed in the bibliography were also of great assistance.

It was these sources, together, that enabled me to reconstruct the story that follows.

Introduction

Just like every other evening, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canadas prime minister, headed to his office to dictate his diary entry to his secretary. It was a habit he had maintained for decades, even in the thick of World War II. The entry from that dayAugust 6, 1945would occupy several typed pages. First, he would relate the events of the day, which began typically enough with matters of domestic policy but, more importantly, he would recount a crucial moment that was to mark a turning point in history.

Mackenzie King had learned via ministerial memo that the first atomic bomb had been dropped on a Japanese city. Once the shock of the news wore off, the prime minister of Canada, a country aligned with the Allies, evoked the strange sense of hope generated by the explosion: Naturally, this word created mixed feelings in my mind and heart. We were now within sight of the end of the war with Japan. Mackenzie King ardently hoped that this massive destruction of human life would be the last, and that it would bring an end, once and for all, to the painful conflict between Japan and Canada that began in 1941. He pondered with horror what might have been the outcome had it been the German scientists who won the race to develop the bomb, suggesting the British race would have been entirely wiped out.

The prime minister also acknowledged in his diary that day the scientific accomplishment the Americans had just achieved. After all, he knew only too well how difficult it was to tame the atom. For the past two years, his country had been home to a laboratory hidden away in the city of Montreal that had been devoted to that very challenge. While Mackenzie King noted with satisfaction in his diary how extraordinary it was that the nuclear project had been kept secret during that time, he nonetheless expressed his apprehension about certain Allies: I am a little concerned about how Russia may feel, not having been told anything of this invention or of what the British and the U.S. were doing in the way of exploring and developing the process.

Although Mackenzie King was certainly aware of the stakes surrounding the atomic bomb, thanks to its ramifications in Montreal, he had no knowledge of certain episodes that had played out in his own country. And Montreals atomic adventure had more than its share of drama

Origins of the Laboratory

Arrival of Hans Halban in Montreal

For a man arriving in Montreal in 1942 for the purpose of working on a British-led project to develop an atomic bomb, it would be in his interest not to be mistaken for a Nazi! That was surely something front of mind for Hans von Halban, the first man to direct this monumental project. With his German-sounding name and slight German accent, the physicist must have bitterly regretted the decision made by his grandfather, a senior bureaucrat in the Austro-Hungarian Empire who, at the turn of the century, had altered the familys surname. The von bestowed on him by the Emperor himself was reserved for nobility, and reinforced the names Germanness. In an irony of sorts, several decades later, his grandson would drop the nobiliary particle in an attempt to obscure his roots as an Austrian noble. When Hans Halban arrived in Canadas largest city in early November of 1942, he was keenly aware of the challenges that lay ahead.

Halban was a man of average height, with a high forehead and piercing gaze. He was charming, self-assured, and perfectly at ease in social situations. Born in Germany in 1908, he spoke English and French fluently. These were all traits he would need to draw on to carry out his perilous mission: Hans Halbans role was to build a nuclear physics laboratoryfrom the ground upin Montreal. He had time to ponder the project during his trans-Atlantic crossing on a low-altitude cruiser (Halban had a heart malformation that prevented him from flying in a conventional aircraft at high altitudes). This privileged mode of transportation suggested Halbans importance in the eyes of the British, who had pinned their considerable hopes on the renowned physicist. With their island under threat from the Nazis, the British had just tasked Halban with relocating their Cambridge-based nuclear laboratory to Canada. The research being carried out there was highly advanced and was key to the countrys military strategy. Whether as a source of energy or a force for destruction, all signs pointed to the atom playing a crucial role in the outcome of the war.

Upon his arrival, the scientist settled in at the Windsor Hotel, one of Montreals most prestigious establishments. At the time, the hotel was located in a rapidly changing neighbourhood that was to become the heart of the citys downtown. Just across the square stood the Sun Life Insurance Companys skyscraper, the tallest building in the British Empire at the time. Hans Halban was soon joined by his wife and his three-year-old daughter Catherine Mauld. While at the hotel, he began meeting with potential candidates to build his team in Montreal. Now all they needed was to find somewhere to conduct their extensive scientific experiments.