Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2006 by Joseph E. Moore

All rights reserved

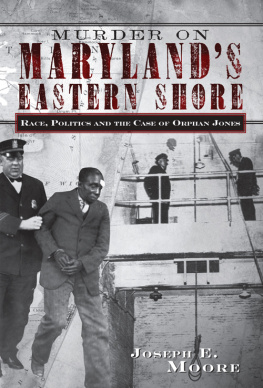

Front cover image: Orphan Jones was removed from the Worcester County jail in Snow Hill in order to protect him from possible mob violence. Notice the bandage over his left eye, surely a result of being hit during the trip from Berlin to the jail or during the interrogation. Baltimore Sunpapers.

Back cover image: The gallows chamber located in a wing of C dormitory of the Maryland penitentiary. It was in this foreboding room that Euel Lee was executed on October 27, 1933, the seventeenth man to be hanged in the penitentiary. (Prior to 1923, executions had been held in the county where the crime occurred.) By 1955, when the state mandated that the gas chamber replace the gallows, seventy-five hangings had taken place here. The building has since been demolished. Courtesy of Maryland Division of Correction.

First published 2006; Second printing 2006; Third printing 2006; Fourth printing 2011 e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.095.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moore, Joseph E.

Murder on Marylands Eastern Shore : race, politics and the case of Orphan Jones / Joseph E. Moore.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978.1-59629-077-8 (alk. paper)

1. Lee, Euel, d. 1933--Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Trials (Murder)--Maryland. 3. Murder--Maryland--Worcester County--History--20th century. 4. Discrimination in criminal justice administration--Maryland--Worcester County--History--20th century. I. Title.

KF224.L44.M66 2006

345.7522102523--dc22

2005033309

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Preface

I am a native Marylander and a proud Eastern Shoreman. I was born in Berlin, near Ocean City in Worcester County, during the third presidential administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. My literal birthplace is located in the middle of the town of Berlin, only several yards from the location of the magistrates office in 1931, which figured in the initial events of the true story that follows. Even though I was not alive at the time of the crime, it is with some difficulty that the tale is told, because of the horrific nature of many of the events which occurred in my home region that I dearly love. The tale recreates the story of a horrible murder in the area, which, because it involved an African American who murdered an entire white family in the segregated, Depression-era Eastern Shore community of Worcester County, caused incredible tensions, racial divisions and turmoil in a normally quiet rural community.

I was elected States Attorney for Worcester County in 1978, and, after taking office, I stumbled across an old, yellowing file in the clerks office of the courthouse. This, it turned out, contained the original documents in the case of State of Maryland v. Euel Lee, alias Orphan Jones. An ancient telegram struck my eye. Dated October 18, 1931, it read: A FTER C ONFERENCE W ITH C OURT H ERE H AVE D ECIDED N OT T O A LLOW A NY C OUNSEL A PPOINTED O R E MPLOYED B Y I NTERNATIONAL L ABOR D EFENSE T O I NTERVIEW E UEL L EE A LIAS O RPHAN J ONES U NLESS S O D ECIDED B Y J UDGE F RANK . It was signed by Godfrey Child, who was, in 1931, the States Attorney for Worcester County. Intrigued, I inquired of Circuit Judge Daniel T. Prettyman as to whether he would grant me a court order to remove the documents from the clerks file. His response was typical for him: Nobody gives a damn, just go ahead and take them. (In the mid-twentieth century, the Eastern Shore circuit court judge was, truly, the boss of the county.)

So, I did.

Thus began what turned out to be a twenty-five-year journey through the history of the case of Orphan Jones. I have spent hundreds of hours looking at the records of the Maryland Archives, reviewing the Enoch Pratt librarys newspaper files in Baltimore and combing through local histories of the Eastern Shore and documents and historical accounts related to the state of Maryland, visiting the areas where the events took place. With the help of H. Furlong Baldwin, formerly the chairman of the board of Mercantile Bank, and Sandy Levy, the library services director of the Baltimore Sun, I gained access to the excellent library of the Sun. Sandy also directed me to the repository of the original newspapers of the Sun editions at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where Tom Beck, chief curator of the Albin O. Kuhn Library and his assistant, John Beck (no relation) were unfailingly cooperative and helpful.

Dr. Edward Papenfuse, chief archivist and director of the Maryland Hall of Records, has been of great assistance in achieving the publication of this story. And my introduction, through Ed, to the website of the archives revealed many sources otherwise unknown to me.

Thanks are due to Vincent Fitzpatrick and Ms. Averil Kadis of the Mencken Room, Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore for their permission to use much of Menckens material that is excerpted in the book.

Jennifer Ketner, Dana Donovan, Kristina Bouton and Sandy Dougan are to be thanked for helping me through the mysteries of computers, recopying text and for formatting this book. Special thanks are due to Mary Humphreys, PhD, for her impeccable and careful proofreading for the second edition of this book.

Janet Ades, the daughter of Bernard Ades, was very helpful in providing me with material that her cousin, James Platt, had found in the National Archives and which I otherwise would not have thought to locate.

The practice of law with its demand on my time has hindered me in the formulation and writing of the book, and my partners and associates in my law firm have put up with literally years of my rambling about the story, normally during our lunch hours together. They really never thought this would ever get written.

My family and friends are to be thanked for their patience and support, especially my daughters Melissa and Jenny and my wife Sue, who have read the manuscript with a critical and unflinching eye toward my mistakes and shortfalls.

I only regret that, during the years, many of the persons who knew the events firsthand died before I interviewed them.

My mother, Bessye Moore, has just (in 2005) celebrated her ninety-seventh birthday, and many of her generation recall the events of this story with startling clarity. Many of them (those who are left) still have an abiding hatred for H.L. Mencken, of the Baltimore Sun, because of the vitriolic manner in which he portrayed Eastern Shoremen in general and the events related herein in particular. Mencken harbored an intense dislike for Eastern Shoremen. One of his famous passages (penned well prior to reapportionment of the legislature of the state of Maryland) bemoaned the fact that the vote of one malarial peasant on the Eastern Shore of Maryland equals that of ten Baltimoreans. To those Depression-era folks still alive on the lower shore, Mencken remains a subject of contempt even today, nearly fifty years after his death.