Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

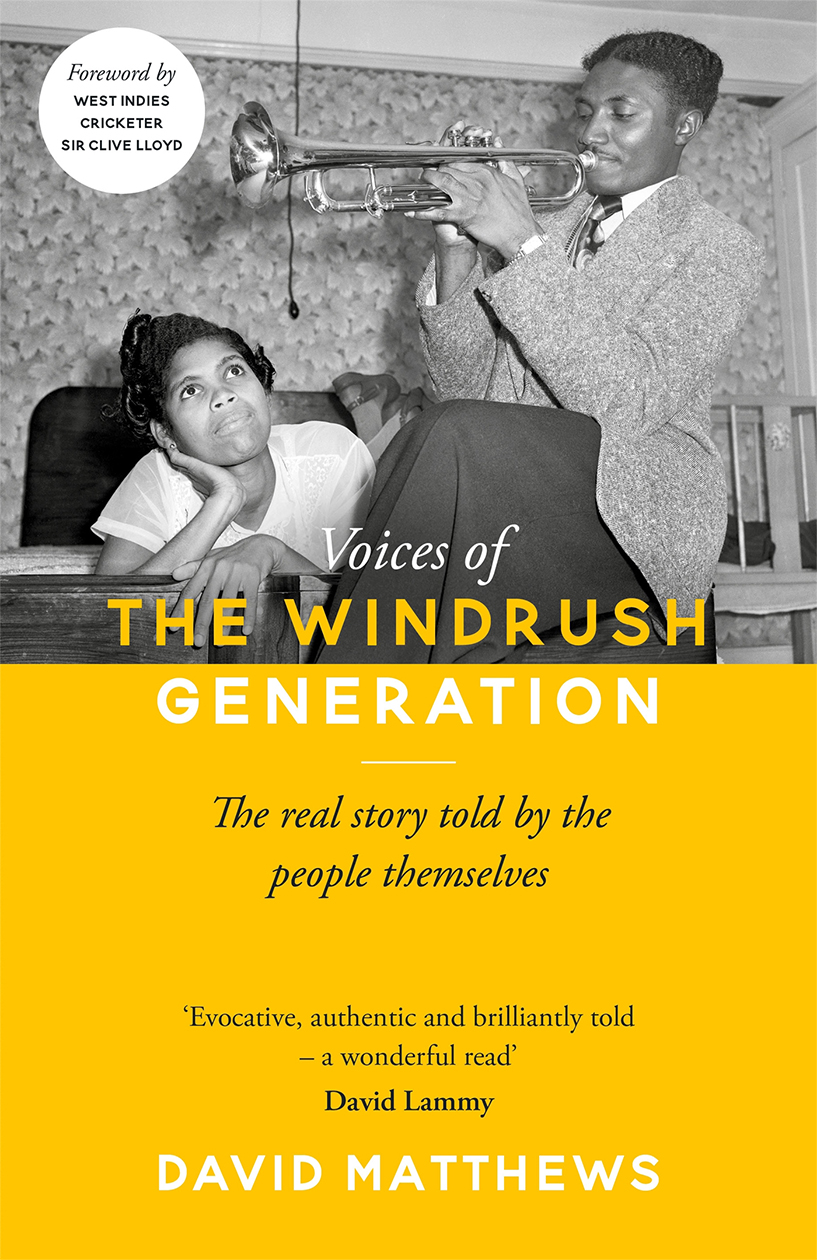

Voices of

THE WINDRUSH GENERATION

Voices of

THE WINDRUSH GENERATION

The real story told by the people themselves

DAVID MATTHEWS

Published by Blink Publishing

2.25, The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London, SW10 0SZ

www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

facebook.com/blinkpublishing

twitter.com/blinkpublishing

Hardback 978-1-788701-34-1

Ebook 978-1-788701-53-2

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and set by seagulls.net

Copyright David Matthews, 2018

David Matthews has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Blink Publishing is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

For Barbara Monica Matthews

Contents

I first came to Britain in 1967 at the tender age of 23 to play for Haslingden Cricket Club in Lancashire, some 19 miles due north of the industrial powerhouse that was Manchester. Known locally for its stone, wool and cotton industries from the 18th century right up to the 1950s, Haslingden was, and still is, by all accounts, a very small town. It seemed to embody everything I associated with the warm beer, balmy summers and village green image of English cricket Id formed back home in my native Guyana, largely due to Path newsreels, hours of listening to cricket on the BBC World Service and, of course, first-hand accounts of fellow West Indians who had already journeyed across the Atlantic like so many Dick Whittingtons.

In those days, British Guiana, as it was then known, was still part of the British Empire. Independence wouldnt come for nearly a decade yet. Arriving in Haslingden I had a sense of not coming to the motherland but drilling down into the mother lode of England, as having already made my Test debut for the West Indies the previous year, and being born and raised in the Caribbean, I had a great sense of being a stranger in a strange land.

But I was not the first West Indian to play for Haslingden. Over three decades earlier, in 1933, Jamaican batsman George Headley had signed as a professional for the club following the West Indies tour of England, playing for Haslingden until 1939 and ending due to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Defying a colour bar, which had existed since the birth of West Indies cricket in the 1880s, at the beginning of 1948 six months before the arrival in Britain of the SS Empire Windrush Headley became the first black captain of a West Indies team, albeit for one Test match in Bridgetown, Barbados. And who was the opposition? England.

In his book The West Indies: Fifty Years of Test Cricket, Tony Cozier wrote that the prohibition of a black captain was historically understandable at a time when it was generally considered by the ruling classes that the black man was not ready for leadership political, social, sporting or otherwise. What this colour bar demonstrated, at the dawn of the Windrush generations evolution, was that West Indians, who would face years of prejudice, discrimination and racism while making a mark in Britain, were exchanging one climate of inequality and hostility for another.

Yet Headley was far from being the only notable West Indian cricket playing or otherwise in Britain at the time. Between 1929 and 1938, Trinidadian and West Indies cricket legend Learie Constantine played for Nelson Cricket Club, also in the Lancashire League, and went on to work for the Ministry of Labour and National Service as a Welfare Officer responsible for West Indians employed in English factories. In 1943, a London hotel manager refused service to Constantine and his family because of their race. Constantine successfully sued the hotel company in a case that would bring about a sea change in UK race relations. In 1954, Constantine already an accomplished journalist and broadcaster qualified as a barrister. Two years after I arrived in Britain, Learie became the first black man to sit in the House of Lords.

While playing for Nelson, Constantine invited his friend, countryman and author, C.L.R. James over to help write his autobiography, Cricket and I. James, a cricket aficionado, went on to write arguably one of the finest books ever written on the game, Beyond a Boundary.

The Grenadian singer and pianist, Leslie Hutch Hutchinson, who lived in Britain for over 40 years, was one of the countrys biggest stars during the twenties and thirties. At one point, Hutch was the highest paid entertainer in Britain. At the other end of the spectrum, in 1912, the ground-breaking Jamaican political activist, Marcus Garvey, emigrated to Britain years before the likes of fellow Jamaican and co-founder of cultural theory, Stuart Hall, or Trinidadian Nobel Laureate, V.S. Naipaul, or the Grenadian Dr David Pitt, Britains first black Parliamentary candidate.

But even before these titans of sports, the arts, academia and politics arrived there was Crimean War heroine, Mary Seacole, a rare female presence in a male-dominated Hall of Fame of pre-Windrush notables. And what of the slave soldiers of the West India Regiment? It is estimated that between 1795 and 1807, 13,400 slaves were bought from West Indian plantations to fight for the regiment in theatres that included the Napoleonic War and the First World War.

What Seacole, legions of West Indian soldiers, and Constantine, James, Hutchinson, Garvey, Hall and Naipaul have in common is that while being born in the Caribbean, they dedicated themselves to British public life. But this is just the tip of a Caribbean iceberg! What about Bill Morris, Baron Morris of Handsworth (Jamaica), the first black leader of a major British trade union? Or Bernie Grant (Guyana), who in 1987 was one of three of Britains first black MPs? Or former Attorney-General, Patricia Scotland QC (Dominica), or Baroness Valerie Amos (Guyana) who, as Director of SOAS, is the first black woman to head a UK university?

From decade to decade, century to century, West Indians have educated, entertained, inspired and led in Britain, regardless of colour or creed, without fear or favour. Because of my cricketing career both on and off the field since the early 1960s and, I guess, reaching its apex in the glory days of West Indies cricket from the 1970s to the 1990s, I have very much been associated with being Guyanese, West Indian and African-Caribbean. During that period of global cricketing success, I captained the West Indies from 1974 to 1985 and was constantly reminded of the role, and the responsibility, that the Windies had in instilling a sense of pride in Britains Caribbean community, a community that at times felt dislocated from its roots and under threat from a hostile environment.