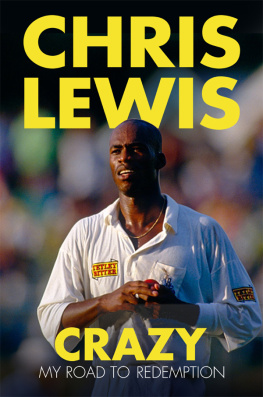

Chris dedicates his work on this book to Clare, Lotte and Tom.

David dedicates his work on this book to his mother.

PREFACE

No, Janet, Its One of My Writing Thingies

What the hell do you think youre doing!! hissed Janet, her eyes flaming with anger and her voice almost incoherent with rage. Voting was drawing to a close in the 2005 general election and Janet, a family friend and longtime Labour voter, had spotted me outside the polling station in East Sheen, in the wealthy borough of Richmond in south-west London. I was wearing a bright blue Conservative Party rosette with the words Vote Conservative emblazoned on it. I was also acting as a teller for the Tories, gently hassling voters for their polling card numbers as they went into the polling station, set up for the occasion in a local primary school.

At many a left-wing dinner party poor Janet had listened to me jawing on into the night about some socialist theme or other; I had even droned on to her about left-wing politics during chance encounters on the local streets. To Janet, I was a fellow member of the red team. How can you be wearing that that thing? she gasped in horror, jabbing at the blue rosette, and after that revolting election campaign! Physically cowed by Janets onslaught, I tried simultaneously to hide the blue rosette under my anorak I thought she was going to rip it off and hunched up in anticipation of a blow.

This is not what you think it is, Janet. I cant really talk about it now, I gabbled. To my horror I saw another official Tory teller an elderly woman with Margaret Thatcher hair and a piercing gaze was bustling towards us with her blue ribbons waving in the breeze. Again I pleaded with Janet through clenched teeth and a fixed smile and gave what I hoped was a begging, puppy dog-like look. Pleeeeze Janet its one of my writing thingies! we can talk about this later

Janet shot back: Oh no we cant! In fact, make bloody sure you never talk to me again! Have you got that? I acknowledged her with a sad and shame-filled nod and must have looked, I realized, like a naughty schoolboy. And with that Janet harrumphed off into the polling booth to cast her vote.

On Monday 11 April 2005 my friend the writer David Matthews officially took up residence at my house in Richmond in what the local tourist board still liked to call Surrey but which was, in reality, part of the sprawling but very prosperous southwestern suburbs of London. And with that one of the most extraordinary episodes in my life began. The two of us had decided to join the already faltering Conservative general election campaign taking place that year and write about it from the inside. It was to be a literary and investigative project, and we would be working largely undercover.

David and I were interested in finding out what sort of person might, these days, become a Conservative activist and what made them tick. That was the official Mission Statement. But we had another, even more powerful, motive. We just thought that joining the Conservative Party would grant us access to all sorts of situations which would ordinarily pass us by, and we would get to meet people we would never ordinarily meet. The project, as things turned out, was to last well beyond that election on and off, in fact, for the next three years.

Supposedly, we reasoned, Conservatives should be very ordinary people. That was what the name almost literally meant sort of ultra-normal. But just looking at the statistics for membership it became clear that this was no longer true if it ever had been. Joining a political party of any sort was, by 2005, pretty deviant behaviour. (Admittedly, by the time our journey into Blue Britain was over, the image of the Conservative Party had improved considerably, and we were there to see, from the inside, how that transformation took place.)

But in 2005 the Tories were extraordinarily unpopular, especially with just about anyone under fifty. They struck David and me as more like a weird and unfathomable cult than a once unstoppable election-winning force. This was the Conservative leadership era, remember, of Michael Howard and a pre-makeover Ann Widdecombe, when the partys claim to represent modern Britain seemed more than a little tenuous. So we saw voluntary activism in the Conservative cause as so unusual that it represented a sub-culture potentially more interesting than the groups and scenes we had reported on in the past such as football hooligans, Muslim fundamentalists, professional boxers, tabloid journalists, gun-wielding inner-city criminals and the yacht-dwelling super-rich. All of those groups were, to a degree, tricky to understand, but their world-views were, we reckoned, a lot easier to figure out than the mentality of local Conservative activists in 2005.

I was living in a Conservative ward, consisting of lots of multi-million-pound residences stretching up to the walls and iron gates of Richmond Park, a royal deer park with actual herds of deer in it. The parliamentary seat was held for the Liberal Democrats at the time by Jenny Tonge, a medical doctor who seemed to have pretty extreme views about most things, especially the Iraq war. Jenny had endured a tabloid lynching after she advocated bombing the Taliban in Afghanistan with money and loaves of bread instead of cruise missiles. And yet the Richmond Tories could make no headway against somebody as plainly cranky and annoyingly worthy as her. Why was this happening? Had the population of Richmond, consisting as it did of one of the largest concentrations of rich, elderly white people in the country, suddenly decided that even it didnt like the Tories?

Our plan was to treat the Conservatives and a broader swathe of small c conservatives (such as country sports enthusiasts, village cricketers and the Womens Institute) as a broad tribe or clan whose social anthropology we wished to study. We would work our way through their habitats in the manner of Colonel John Blashford-Snell (the pith-helmeted jungle explorer who turned up at one of the Conservative drinks parties we attended) and note their rituals. As we discovered, some of the people we met really were, in the nicest possible way, from another planet not necessarily a worse planet than the one David and I live on, but certainly a very strange one.

David and I worried briefly about the ethics of joining a party which we did not approve of, and aiding a cause that we felt was neither in the interests of ourselves nor the people we cared about and loved. Would we be able to live with ourselves if we accidentally helped to get a Tory elected to Parliament? Wouldnt we be helping to propagate a world-view with which we fundamentally disagreed? What if the Tories liked us and started trying to make proper friends with us? We decided, though, that getting the inside track on the Conservatives and conservatism was a Legitimate Journalistic Exercise in the Public Interest: and that, together with it being fun and broadening our horizons a bit, trumped all our other concerns.

In the appropriately anonymous surroundings of a Battersea pub we decided that we would only be evasive if we needed to be. (If we said we were journalists we would get the usual flim-flam). We felt perfectly justified in taking this approach, because working as reporters we knew that Conservatives, like almost all politicians, arent above being evasive themselves. And while working on this book, we saw Conservatives giving enormously misleading accounts of things to journalists who approached them overtly with, as it were, their press cards poking out of their hat rims. We felt we needed to get beyond that.

So I admit that some mild subterfuge was involved in the process of researching the book. But there was never any malice. Most of the people we met were, we felt, essentially harmless and, if anything, just a bit lost or stuck in a rut. The Conservative Party, and other Conservative institutions, offered these people a much-needed anchor in their lives. We felt sorry for some of those we met, liked one or two and were repelled by a few.

Next page