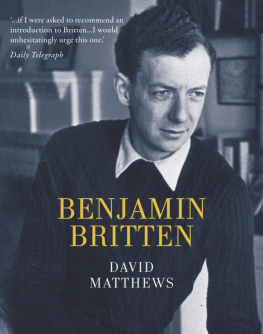

Preface to the 2013 Centenary Edition

At his centenary, Brittens status as one of the great composers of the past century seems secure. There will be performances of his work throughout the year, not only in this country but around the world, for Britten is better known and understood internationally than any of his compatriots. As a writer of opera, he has no rival among his generation. Many composers go through periods of neglect after their death. This never happened to Britten: in contrast, much of his music that was undervalued in his lifetime or had been suppressed, including a number of his early works, has emerged into the light; and several works that had been unjustly criticised notably Gloriana and Owen Wingrave have been re-evaluated.

The first edition of this book was published ten years ago. At the concert to launch the book, a previously unknown work written when Britten was 16, Two Pieces for violin, viola and piano, was given its first performance, together with a premiere of a work of mine. Two Pieces is only one of many astonishingly accomplished works that Britten wrote when he was studying with Frank Bridge, being introduced to the latest music from Central Europe and eagerly absorbing it, together with the forward-looking music of his teacher. Britten had no interest in getting these works performed in his lifetime many of them he never heard; but some of them, in particular the Quatre chansons franaises and the Double Concerto for violin and viola, have now entered the repertoire. There may be more discoveries to come from his early music, and there are still some mature works that perhaps have not yet found their proper place, for instance the Cello Symphony and the cantata Phaedra.

A number of significant books have been published during the last ten years. The six large volumes of Brittens letters a biography in themselves are now all in print, as are the early diaries, which show what a severe critic of his contemporaries this precocious teenager was. The recent biography of Imogen Holst includes a diary she kept from 1952 to 1954, when she was Brittens amanuensis. It is a valuable record of Brittens musical thoughts and opinions, which he only discussed openly with close friends. In one conversation he admitted that he thought of himself as perpetually aged 13. This was a time when, to quote the Hardy poem he was to set in Winter Words, all went well: he was head boy and Victor Ludorum at his preparatory school, pouring out reams of music, including his first orchestral works, and protected from the grown-up world by his mothers devoted love.

In his illuminating study, Brittens Children, John Bridcut points out that Britten used boys voices in almost 30 of his major works, including 12 for the stage. It is one of the most distinctively original sounds in his music. Britten used the boys voice not only to express his wish to remain in an innocent world, but also to show how innocence was threatened by experience. In many ways Britten was not at home in the adult world, even though some of his best instrumental works for instance the Violin Concerto, the three string quartets and the Cello Symphony evince a fully mature response to the world. This response is sometimes a dark and disturbing one, but it is also one of reconciliation and even joy. Britten also takes refuge from the troubles of the world in the realm of sleep: this is wonderfully expressed in his two orchestral songs cycles, the Serenade and Nocturne, and above all in the opera A Midsummer Nights Dream. In his most ambitious confrontation with the worlds troubles, the War Requiem, Britten offers sleep as the only possible solution: it may be the sleep of death, but it is too a dream of paradise, a vision of unassailable beauty.

It is, above all, Brittens ardent pursuit of innocence and beauty in his music that places it apart from that of his contemporaries, and contributes to its unique quality. We shall be celebrating his unique genius in this centenary year.

David Matthews

2013

Preface

In 1966 I was working as a freelance music copyist and editor in order to finance my intended life as a composer. One of the people who employed me was Donald Mitchell, who had recently established the firm of Faber Music, primarily in order to publish Brittens latest music. In the spring of 1966, Martin Penny, who was preparing the special rehearsal score of The Burning Fiery Furnace, fell ill, and someone was needed in a hurry to complete the score. I was asked, and was able to finish the job in time. I went to the premiere of the new piece at the Aldeburgh Festival, which took place in Orford Church. After the performance I was introduced to Britten, who said kindly I hope you enjoyed hearing your notes. Later that year I incorporated Brittens revisions into the score, and since I seemed to have passed the necessary test of competence I became, over the next four years, an occasional assistant to Brittens regular music assistant Rosamund Strode. Among the tasks I was assigned were preparing the rehearsal score of The Prodigal Son and the vocal score of Owen Wingrave. I also made a fair copy of the full score of Owen Wingrave, with help from my brother Colin, who later took over from me for the vocal score of Death in Venice. After Brittens heart operation in 1973, I made the vocal score of Paul Bunyan and a reduction for two pianos.

From 1967 to 1970 I also helped with the editing of Brittens music and the works he conducted at the Aldeburgh Festival, for instance Idomeneo, of which, in the tradition of Mahler and Strauss, he had made his own edition. I attended many of his rehearsals. I used to go to Aldeburgh to stay for extended periods, and was assigned an office in the former stable buildings beside the Red House, which are now part of the BrittenPears Library. Most days Britten would call in to say hello; sometimes I would join him for tea, and on one occasion I had supper with him and we talked at length about the contemporary music scene. I think he felt a little isolated from it but still concerned to keep in touch with what was going on. After supper he played me some gramophone records: Kirsten Flagstad singing Sibelius I remember his enthusiasm for her voice and the Indian flautist Pannalal Ghosh, whose playing greatly interested him at that time and influenced some of the melodic writing in The Prodigal Son.

I was shy and somewhat in awe of Britten not surprisingly, as he was the first adult composer I had met and now feel that I could perhaps have made more use of the opportunities I was given. I could have shown him my music, for instance, but didnt. I was somewhat wary of the Aldeburgh scene, and a little afraid of becoming too closely drawn into it. I was also aware, as everyone was, of Brittens hypersensitivity and that one had to be careful not to upset him by venturing any rash opinions. He, I must say, was never anything other than kind, considerate and helpful.

I realise what an extraordinary privilege it was for me to have been an apprentice in his workshop, observing at close hand a great composer solving all the problems of composition and performance in his supremely practical way. It is the best kind of training for a young composer, and this book is in one sense an expression of my gratitude to the man who made it possible.

I should like to thank the staff of the BrittenPears Library, in particular Nicholas Clark, Elizabeth Gibson and Jennifer Doctor, for their generous help while I was researching the book. I am grateful to the Trustees of the BrittenPears Foundation and of the Lennox Berkeley Estate for allowing me to quote from copyright material, which is not to be further reproduced without written permission from the Trustees. I owe a great deal to the existing Britten literature, above all to Humphrey Carpenters full and detailed biography and the two published volumes of Brittens diaries and letters, edited by Donald Mitchell and Philip Reed. The staff at Haus, especially Barbara Schwepcke, were exceptionally understanding and helpful, and Peter Sheppard Skaerveds editorial supervision was invaluable. Mark Doran and Jenifer Wakelyns contributions to the final text as unofficial editors were extraordinarily scrupulous and thorough (Mark Doran also wrote the sidebar on Hans Keller). David Harman, Jean Hasse, Colin Matthews, Donald Mitchell and Norman Worrall also read the text and made extremely helpful comments. In addition Judith Bingham, Jonathan Del Mar and Rosamund Strode supplied valuable details.